Dr. Wible’s keynote delivered at the 19th Annual Chicago Orthopaedic Symposium (begins with a beautiful legacy to the life of Dr. Dean Lorich by Dr. Matthew Jimenez). Downloadable MP3 above.

Thank you. I’m truly honored to be here and extremely grateful that you have given me more than 10 minutes to discuss doctor suicide. Looking at your agenda (three days of q-10-minute lectures back-to-back) as a family doc, I’m just a little blown away that you can cover complex acetabular fractures and mangled lower extremity grade IIIC salvage versus amputation in 10 minutes when I can barely treat a patient with a UTI or step throat in 10 minutes.

I’d like to dedicate my presentation today to Dr. Dean Lorich—and to the many orthopaedic surgeons we’ve lost to suicide. I’ve had the opportunity to get to know many of these men through their colleagues who reported their suicides to me and more intimately through their mothers, sisters and children left behind.

Today, for the first time, I’m sharing my data—what I’ve discovered from investigating more than 1000 doctor suicides—and specifically the suicides of 33 orthopaedic surgeons. Data—often devoid of emotion and humanity—means little without a human face so I’ll start by sharing the incredible lives of two orthopaedic surgeons whom I deeply admire, Dr. Steven Ortiz and Dr. Benjamin Shaffer.

Most of you know Dean. Just curious how many of you know Steve or Ben?

Though we know each other professionally, how many of you feel you really know each other personally—the deep feelings and inner world of your colleagues? I want you to truly know these two men—not just as skilled surgeons—but as the amazing human beings we were blessed to have on this planet. And then I’d like to invite you to get to know each other (while you are still living) as deeply as I’ve gotten to know Steve and Ben posthumously. I’ll begin with Ben . . .

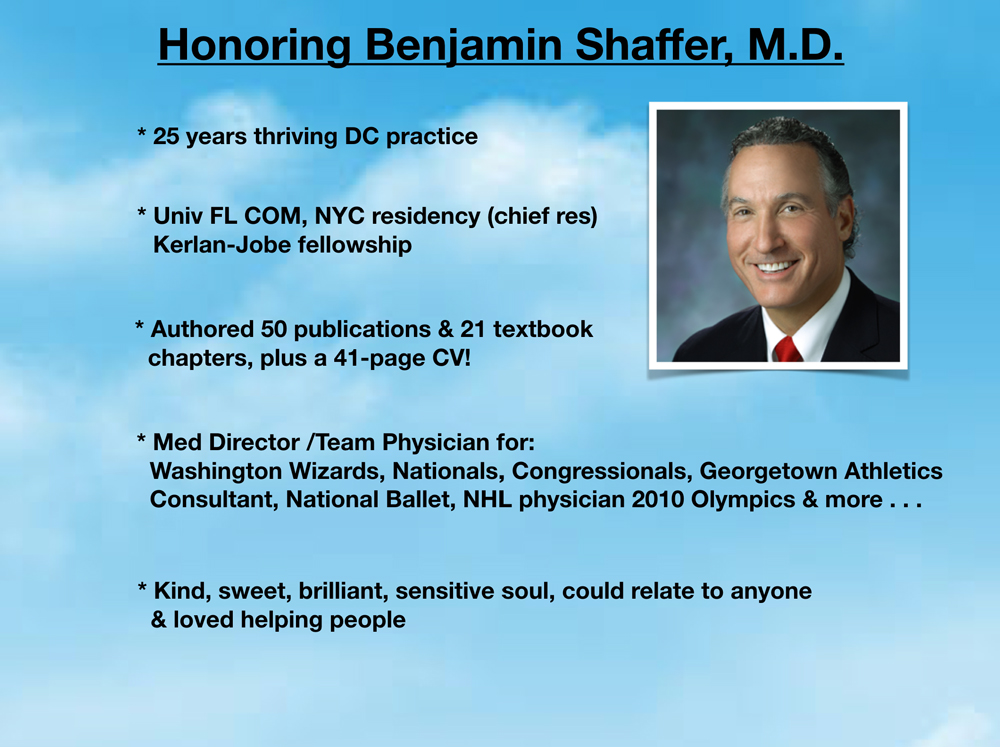

The orthopedic community suffered a devastating loss with the suicide of Dr. Ben Shaffer. He was in practice 25 years as a much beloved and trusted orthopaedic surgeon in Washington DC. Dr. Shaffer graduated from the University of Florida College of Medicine, completed his orthopaedic residency in NYC where he was chief resident, then specialized in sports medicine with a fellowship at the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic.

The author of more than 50 publications (21 were textbook chapters), Dr. Shaffer trained orthopaedic surgeons around the world. He has an impressive 41-page CV (officially the longest I’ve ever read). He was the medical director or team physician to a gazillion professional sports teams in the DC area. Dr. Shaffer was also consultant to the National Ballet, NHL physician for the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver, PGA Golf Tour, Women’s World Cup Skating, and the list goes on . . . Impressive! Right?

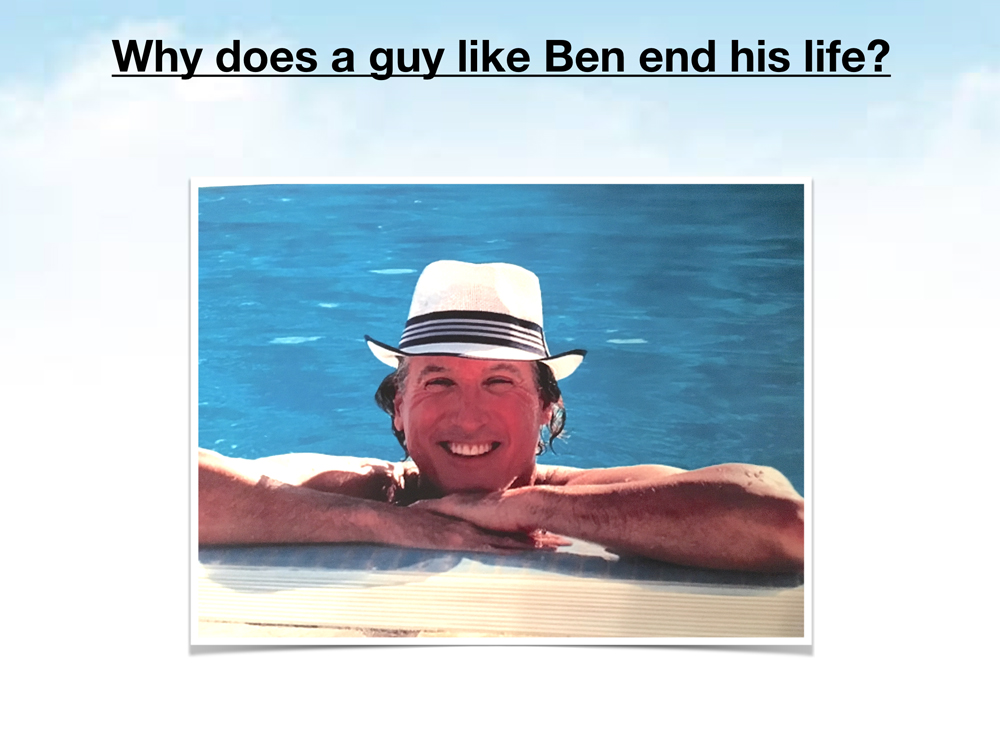

Yet Ben was more than a surgeon, he was a kind, sweet, brilliant sensitive soul who could relate to anyone—from inner city children to supreme court justices. He was gorgeous and magnetic and he loved helping people. So why does a guy this successful end his life?

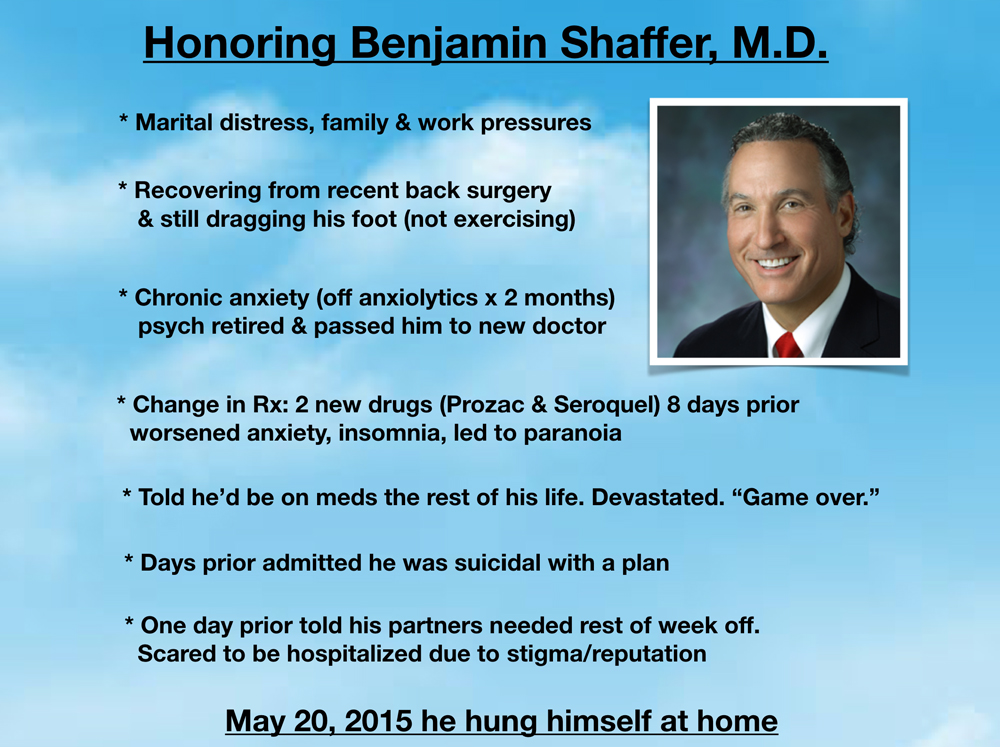

As with most suicides Ben’s was multifactorial. He had marital distress, diminishing reimbursement, and personal health problems. He was recovering from recent back surgery and still dragging his foot so he couldn’t run or work out (activities that would have made him feel better).

Ben also had chronic anxiety. He saw multiple therapists during his lifetime. His psychiatrist had recently retired and passed him on to a new one who didn’t know him. He had been on anxiolytics for years and was weaned off two months before his suicide. Ultimately it was Ben’s uncontrolled anxiety and insomnia (related to sudden change in medication regimen) that led to his death. For insomnia, he was told to take Benadryl or meditate—both ineffective as he was still sleeping just two or three hours per night and trying to operate and see patients each day.

Eight days before he died, he was prescribed Prozac and Seroquel which worsened his insomnia, increased his anxiety, and led to paranoia. Then his psychiatrist told Ben he’d be on medication for the rest of his life. Ben was devastated, hopeless that he’d ever have a normal life. Ben told his sister he felt backed into a corner with no good options and it was “game over.”

Days before Ben died, his therapist asked him if he was thinking of suicide and he said, “Yes.” He then asked Ben if he knew how he would do it and Ben said, “Yes.” He then asked, “Are you going to do it?” Ben said, “No.” (Ben was smart enough to know that “yes” could potentially cause a problem for a physician.)

Ben knew he should check himself into a hospital, but he was panicked because of career ramifications due to the stigma attached to doctors seeking help for mental health. He was terrified that he’d lose his patients, his practice, his marriage, and that everyone in DC—team owners, players, patients, colleagues—would know about his mental health problems and he’d be shunned.

The night before he died, Ben finally told his partners he needed the rest of the week off because he wasn’t sleeping well. He was ashamed, yet they were fine covering for him. Ben left the hospital in sheer terror. He wanted to tell them that he had changed his mind.

Though he had slept that night, he awoke utterly wiped out on May 20, 2015. He had just returned from driving his son to school when he hanged himself on a bookcase with rope from a box that had been delivered earlier in the week. He left no note. He left behind his wife and two children.

Dr. Steve Ortiz had a very different career trajectory, yet suffered the same outcome as Ben.

Steve was one of the most thoughtful, kind, compassionate, and highly ethical men you could ever hope to meet—especially if you needed back surgery.

Though we never met, I feel I know his heart and soul as my brother in medicine. Maybe it’s because we’re the same age and he went to Sheldon High School right down the street from me in Oregon.

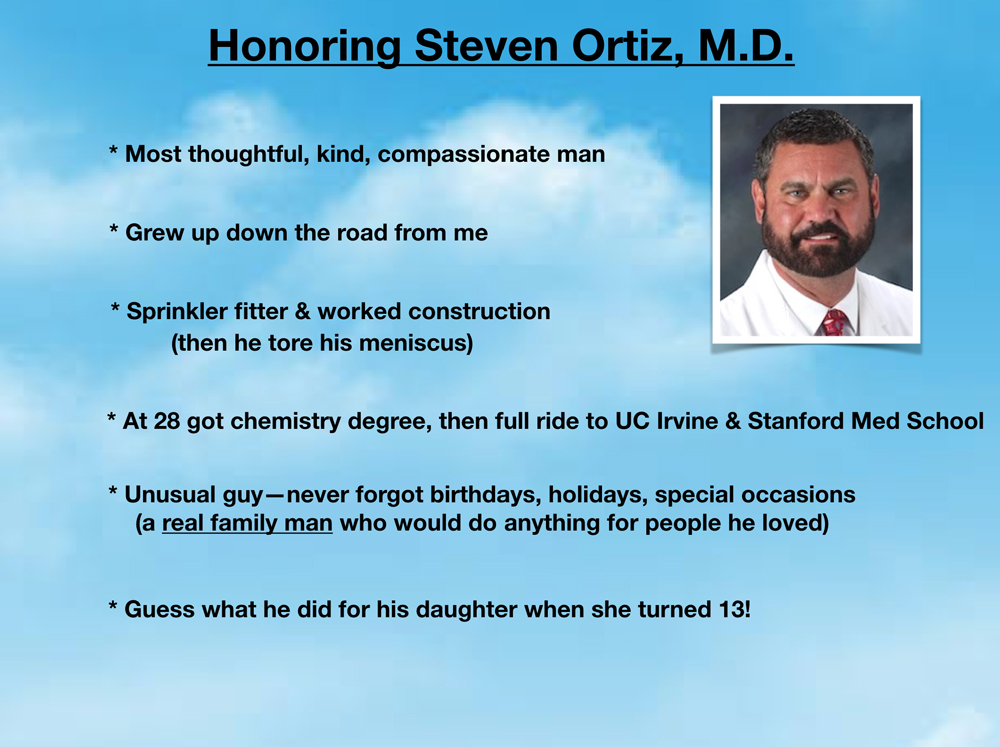

After high school, Steve was a sprinkler fitter for 10 years then did construction. One time when working construction, Steve tore his meniscus. He had surgery immediately. On follow up when the doctor showed him his x-ray he almost passed out and had to be helped to sit down by the nurse. He literally couldn’t stand looking at his own x-ray.

He returned to school at 28 earning a chemistry degree from Fullerton Community College then a full scholarship to UC Irvine and Stanford Medical School, orthopaedic residency in New York and spine surgery fellowship in Minneapolis—a total of 19 years of medical education!

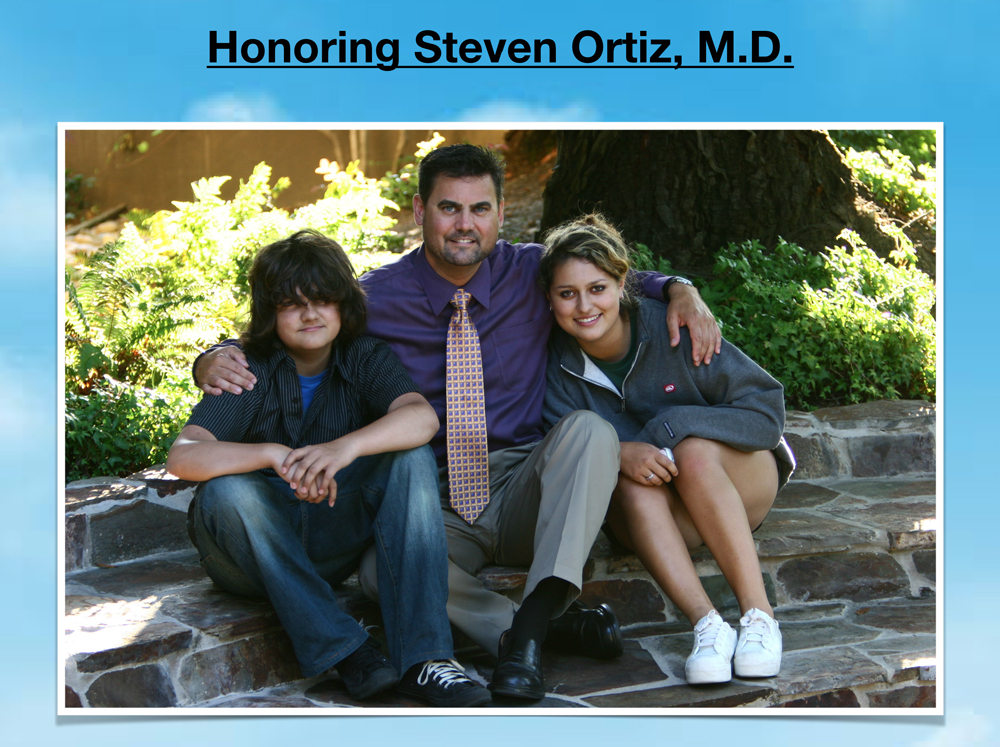

Steve was one of those unusual guys who never forgot birthdays, holidays, or his family on special occasions. You’ll never guess what he did for his daughter’s thirteenth birthday . . .

Since Steve had moved his family to Stanford for med school just before his daughter turned thirteen, she hadn’t made many friends so didn’t know how to celebrate her birthday. On her birthday her dad came home and told her he rented the entire medical school auditorium for the afternoon and he invited her whole soccer team to watch a movie and help her celebrate. He even rented a popcorn machine and bought everyone candy.

Yet Steve—such a devoted family man—had to sacrifice relationships with the very people he loved the most so he could help and heal others. With his kids and wife finally settled in California, he was distraught having matched in New York for orthopaedics. During his five years of residency he only got to see his kids once each year. That marriage eventually failed and he remarried a woman who wanted to be near her family in Florida. So, of course, Steve agreed. (He had trouble saying no!) After fellowship, he set up his practice in a Florida hospital where he was adored by patients and staff (just read comments on his suicide news article). He was always ready to help others. When one of his patients became ill, he flew home from his vacation to care for her!

Steve—the ultimate fix-it-guy—didn’t like when things were in disrepair. There was a huge pothole in the hospital parking lot that was driving everyone crazy, but it was never taken care of by the powers that be until Steve went to a local hardware store and bought several bags of cement and gravel. Imagine a spine surgeon out in the hospital parking lot repairing potholes before work.

But Steve’s problems with the hospital were deeper than parking lot potholes.

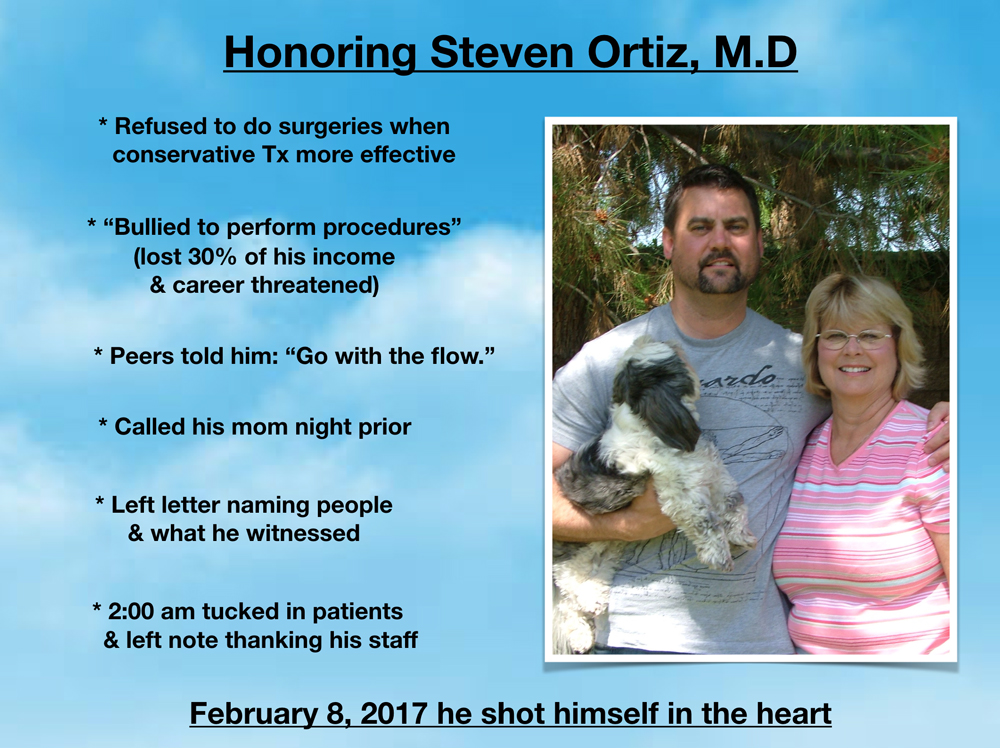

He refused to do surgeries when conservative treatments would be safer and more effective, particularly for elderly patients. Yet the hospital was making money from all these procedures and Steve felt he was being bullied to perform unnecessary surgeries. His colleagues said he should just “go with the flow.” He wanted to leave and they wouldn’t let him. They referred fewer patients to him and he lost 30% of his income. They threatened to ruin his career.

He called his mother the night before he killed himself to share these details. She knew none of these challenges he faced every day until that 30-minute phone call. He had already planned it. At 5:00 pm the night before he wrote a letter naming people and what he witnessed. (Due to an active investigation I’m not at liberty to share more.)

Dr. Ortiz was an open-hearted truth teller, a whistleblower who had only been out of training for three years. On February 8, 2017 at 2:00 am he tucked his patients in and wrote orders to make sure they were all okay. He sent a thank you note to a surgical nurse asking her to thank all his staff for taking wonderful care of his patients. In that note, he told her he decided to “check out.” At 3:00 am he went out to the hospital parking lot (the one where he repaired the pothole) sat down in his truck, and shot himself in the heart.

So how did I get involved in these crime scenes? Why am I so obsessed with doctor suicides? Three reasons. 1) I was a suicidal physician in 2004. I thought I was the only one. Maybe I was just too sensitive and idealistic. I have a personal stake in this issue. I feel it to my core. 2) Eight years later, I discovered doctor suicide is quite literally a hidden epidemic! It came as an absolute shock that so many of my colleagues were dying by suicide. 3) What created my relentless 24/7 obsession was the discovery that these suicides were being covered up—by my very own profession! That’s when I got pissed and I couldn’t shut up.

Full disclosure: I have OCD. My obsession—my disturbing recurrent thoughts that I ruminate over are about why all these doctors are dying by suicide. My compulsion—my daily (even hourly) ritual is tracking all the names and details of each case as they come to me. I’m a strong believer of channeling my mental illness into something productive. So rather than wash my hands compulsively, I’m tracking doctor suicides. By nature, I’m really more of an investigative reporter trapped in a doctor’s body. I’m the type of person who can’t stop a project until it’s completed. Like Steve, I’m a truth teller and a whistleblower. I never went looking for these suicides. These suicides found me.

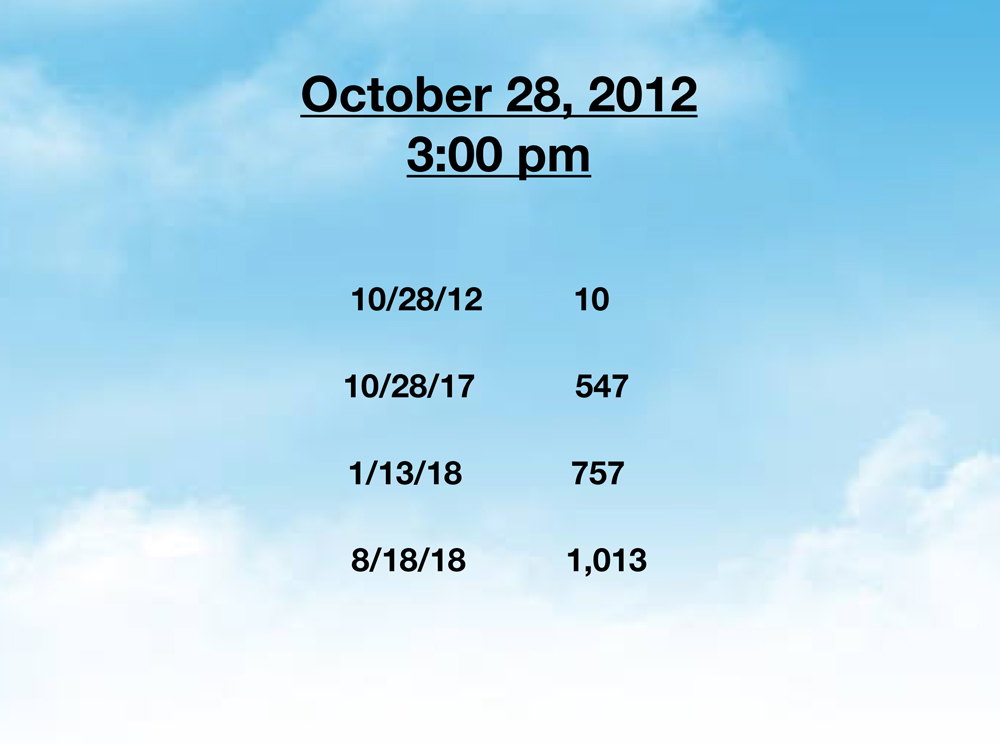

On October 28, 2012, at 3:00 pm my life changed forever.

I was sitting at the memorial service for the third doctor we lost to suicide in my small town—in just over a year. Top-rated doctors. Suddenly gone. Yet during the entire service nobody uttered the word suicide aloud. Kind of hard to solve a problem when nobody will talk about it. Everyone kept whispering “Why?” I wanted to know why. Sitting in the second row at that service I started counting dead doctors—doctors who died by suicide (or highly suspicious circumstances later confirmed as suicide). I suddenly realized BOTH men I dated in medical school—who died at 44 and 39 years old leaving wives and children behind—were likely suicides too! Later, I confirmed both overdosed.

Within a few minutes I had counted 10 doctor suicides.

I had to leave the service early because that evening I was teaching a business retreat for physicians who wanted to launch successful independent practices as I have (Yes! I’m one of the few rogue solo docs out there stilling doing house calls). On my two-and-a-half-hour drive up into the mountains I continued to obsess on doctor suicide: Maybe it’s just the men that I date who die by suicide . . . Maybe Eugene, Oregon, is a hotbed of physician suicides. (People have actually accused ME of only dating guys who die by suicide and choosing to live in a town where so many doctors die by suicide.) Am I really the only one losing my friends, lovers, colleagues to suicide—ALL of them doctors!? (FYI: I’ve never lost any non-physicians in my life to suicide.)

When I arrived at the retreat, I opened the initial session with two questions: “How many of you have lost a doctor to suicide?” All hands were raised. Then I asked, “How many of you have considered suicide?” All hands remained up—including mine—except for a female nurse practitioner. By the end of the retreat they had all submitted names of these doctors on sticky notes, scraps of paper, and index cards.

So I started a doctor suicide diary as a way to track all of these suicides. I bought a beautiful journal with clouds (much like the background on my slides) where I began handwriting all the names and details. Five years later I had a registry with 547 doctor suicides. By then I obviously had to transfer all the data to an online spreadsheet where I’m tracking by case number, name, age, specialty, date, location and method suicide, plus any circumstances or backstory. All the while I keep relentlessly writing and speaking about doctor suicide—and people keep contacting me with more and more names for my registry.

I never went looking for these suicides. These suicides found me.

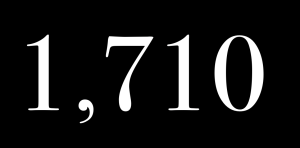

By January this year, I had 757 cases on my registry. As of today I have 1,013.

Meanwhile my house has turned into a shrine for our lost colleagues with entire walls covered with photos of suicided doctors and medical students. And because so many people keep calling and writing me, I’ve been running a de facto doctor suicide hotline from my home for nearly six years now. Yes, I’m up at all hours of the night on the phone with doctors I’ve never met who are having panic attacks at work in between patients and others who are sobbing on the phone with me. Again, I never intended to run a suicide hotline, yet doctors keep calling and I keep answering the phone. Truly a labor of love. After speaking to thousands of suicidal doctors and medical students, I now have a depth of understanding about physician psychology and suicide that is probably very unique in the world.

Here’s what I’ve learned from 1,013 doctor suicides.

High doctor suicide rates have been reported since 1858. Yet 160 years later the root causes of these suicides remain unaddressed.

Physician suicide IS a public health crisis. One million Americans lose their doctors each year to suicide. Yet they are never informed the real reason why they can’t see their doctor who just saved their life or delivered their first child. They’re told to just pick another doctor!

Many doctors have lost several colleagues to suicide. Some have lost up to eight during their career. With no chance to grieve. In fact many medical institutions don’t offer grief counseling services or allow any time off for surviving colleagues who are often forced to work more hours to cover the shifts of their suicided peers—and may not even be permitted to attend their funerals!

We lose more men than women. For every woman who dies by suicide on my registry, we lose four men.

Suicide methods vary by region and gender. Women prefer to overdose and men choose firearms. Gunshot wounds prevail out west. Jumping is popular in New York City. In India doctors are found hanging from ceiling fans.

Male anesthesiologists are at highest risk. Most die by overdose. Many are found dead in hospital call rooms. Google “doctor found dead in hospital” and I would bet most are male anesthesiologists.

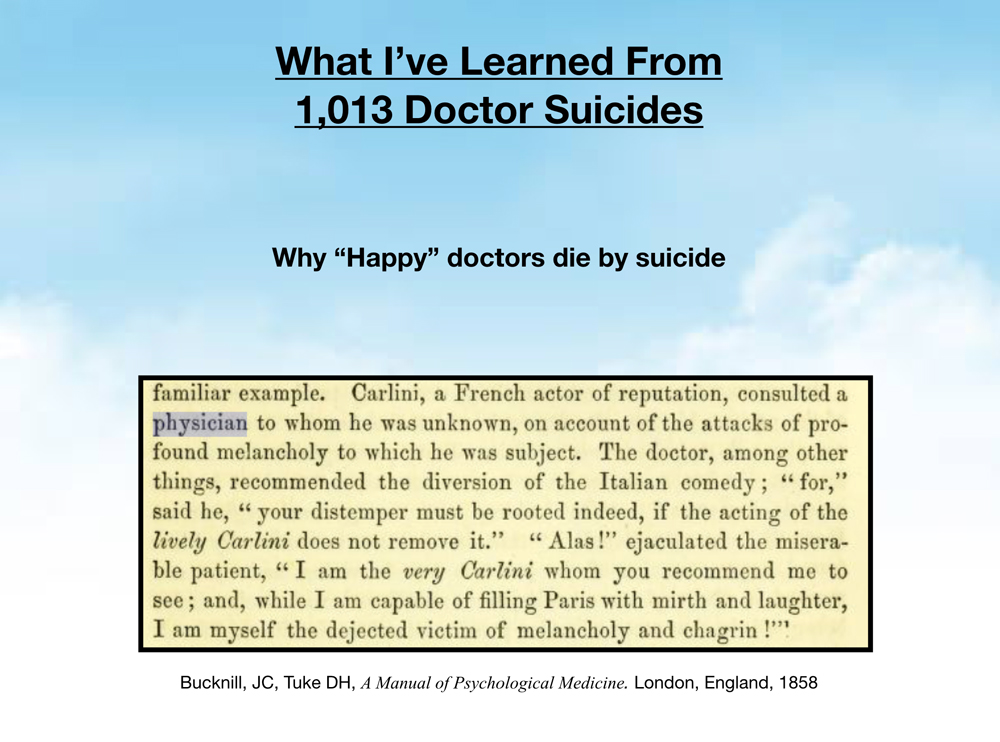

“Happy” doctors die by suicide. Many doctors who die by suicide are the happiest most well-adjusted people on the outside. Just back from Disneyland, just bought tickets for a family cruise, just gave a thumbs up to the team after a successful surgery—and hours later they shoot themselves in the head. Doctors are masters of disguise. Even fun-loving happy docs who crack jokes and make patients smile all day may be suffering in silence. We are all at risk.

There is this perception that “happy” people don’t die by suicide, yet often the people who are most happy on the outside—the very people who spend their days making other people happy (maybe a coping strategy?)—are the ones who are terribly lonely and depressed. Consider reaching out to your “happy” colleagues to see how they are doing.

When I read this excerpt from the 1858 Manual of Psychological Medicine I kept thinking of Robin Williams and all the happy doctors we’ve lost to suicide:

“Carlini, a French actor of reputation, consulted a physician to whom he was unknown, on account of the attacks of profound melancholy to which he was subject. The doctor, among other things, recommended the diversion of the Italian comedy; “for,” said he, “your distemper must be rooted indeed, if the acting of the lively Carlini does not remove it.:” “Alas! ejaculated the miserable patient, “I am the very Carlini whom you recommend me to see; and, while I am capable of filling Paris with mirth and laughter, I am myself the dejected victim of melancholy and chagrin.”

Sensitive souls are at highest risk. Some of the most caring, compassionate, and intelligent doctors choose suicide rather than continuing to work in such callous, uncaring and ruthlessly greedy medical corporations.

Doctors have personal problems—like everyone else. We get divorced, have custody battles, infidelity, disabled children, deaths in our families. Working 100+ hours per week immersed in our patients’ pain, we’ve got no time to deal with our own pain. (Spending so much time at work actually leads to divorce and completely dysfunctional personal lives).

Doctors develop on-the-job PTSD. Especially true in emergency medicine and surgical specialties. Then one day they “snap” like this guy, a friend of mine who against all odds survived his suicide attempt to now enlighten others.

Patient deaths hurt doctors. A lot. Even when there’s no medical error, doctors may never forgive themselves for losing a patient. Suicide is the ultimate self-punishment for the perfectionist.

Malpractice suits kill doctors. Humans make mistakes. Yet when doctors make mistakes, they’re publicly shamed in court, TV, and newspapers (that live online forever). We continue to suffer the agony of harming someone else—unintentionally—for the rest of our lives.

Doctors who do illegal things kills themselves. Medicare fraud, sex with a patient, DUIs may lead to loss of medical license, prison time, and suicide. Even doctors who witness unethical things are at risk of suffering and not being protected as whistle blowers as noted above.

Assembly-line medicine kills doctors. Brilliant, compassionate people can not care for complex patients in 10-minute slots. When punished or fired for “inefficiency” or “low productivity” doctors may choose suicide. Pressure from insurance companies and government mandates further crush the souls of these talented people who just want to help their patients. Many doctors cite inhumane working conditions in their suicide notes. (Assembly-line medicine was 100% responsible for my suicidality in 2004. Thankfully launching my independent practice cured me!)

Bullying, hazing, and sleep deprivation increase suicide risk. Medical training is rampant with human rights violations illegal in all other industries. Physicians have suffered hallucinations, life-threatening seizures, depression and suicide solely related to sleep deprivation. Resident physicians are now “capped” at 28-hour shifts and 80-hour weeks. If doctors-in-training “violate” work hours (by caring for patients) they are forced to lie on their timecards or be written up as “inefficient” and sent to a psychiatrist for ADHD medications. Some doctors kill themselves for fear of harming a patient (or because they did harm a patient) from extreme sleep deprivation.

Blaming doctors increases suicides. Words like “burnout” and “resilience” are often employed by medical institutions to blame and shame doctors while deflecting attention from inhumane working conditions. When doctors are punished for occupationally-induced mental health conditions (while underlying human rights violations are not addressed), they become even more hopeless and desperate.

Doctors fear lack of confidentiality if they seek mental health care. So they drive out of town, pay cash, and use fake names to hide from state medical boards, hospitals, and insurance plans that ask doctors about their mental health and may then exclude them from state licensure, hospital privileges, and health plan participation. (Even when confidential care is available, physicians have little time to access care when working 80-100+ hours per week).

Medical board investigations may increase suicide risk. One doctor hung himself from a tree outside the Florida medical board office after being denied his license. In several of these orthopaedist suicides, ongoing hospital review or loss of privileges played a primary role in their suicides.

Doctors choose suicide to end their pain (not because they want to die). Suicide is preventable. We can help doctors who are suffering if we stop with all the secrecy and punishment. Why not support and care for the people who are here to care for us?

Ignoring doctor suicides leads to more doctor suicides. Thankfully an Emmy-winning filmmaker has completed a documentary that is now shining a light on the physician suicide crisis. View movie trailer here & attend a screening.

Doctor suicide notes reveal the true cause of suicide. Why aren’t we studying these notes? I have a book of suicide letters I’ve published from 53 doctors (many writing to me debating the pros/cons of dying by suicide). The reasons doctors die by suicide are in the book. Download free audiobook here.

Doctors have a great work ethic until the end! Yes, we literally are checking on our patients, reviewing critical labs, and completing out chart notes before we orchestrate our suicides.

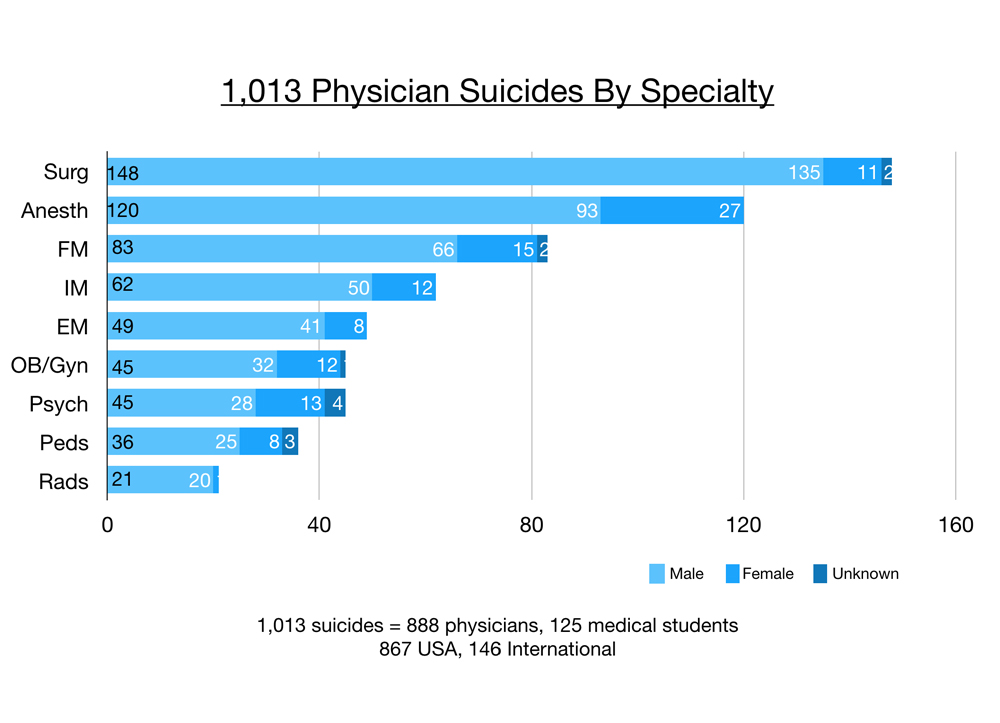

I’ve analyzed 1,013 physician suicides by specialty that have come to me via friends, family, colleagues over the past six years. Of these 1,013, 888 are physicians and 125 are medical students. The majority (867) are suicides in the USA and 146 are international. Surgeons (including surgical subspecialties excluding OB/gyn) have the greatest number of suicides, then anesthesiologists, family docs, internal medicine, emergency medicine, OB/gyn, psychiatry, pediatrics, and radiology. Males (light blue) far outnumber females (darker blue) in all suicides per specialty. The darkest blue represents doctors who have died by suicide with incomplete data on gender.

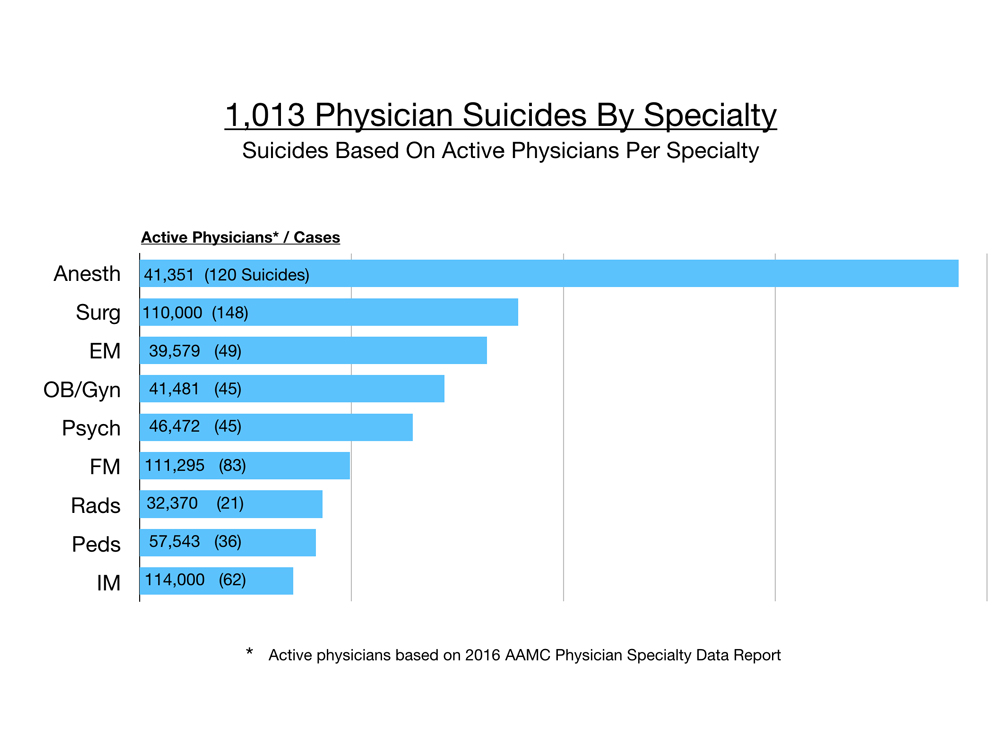

However, when accounting for numbers of active physicians per specialty, anesthesiologists are off the chart and far in the lead. Surgeons are number two, then emergency docs, OB/gyn, and psychiatry. Physicians per specialty are from the 2016 AAMC Physician Specialty Data Report that measured only the active physicians in the largest specialties. Still this gives us a sense of the prevalence of suicide per specialty. Then I analyzed the 148 surgeon suicides and divided them into their subspecialties.

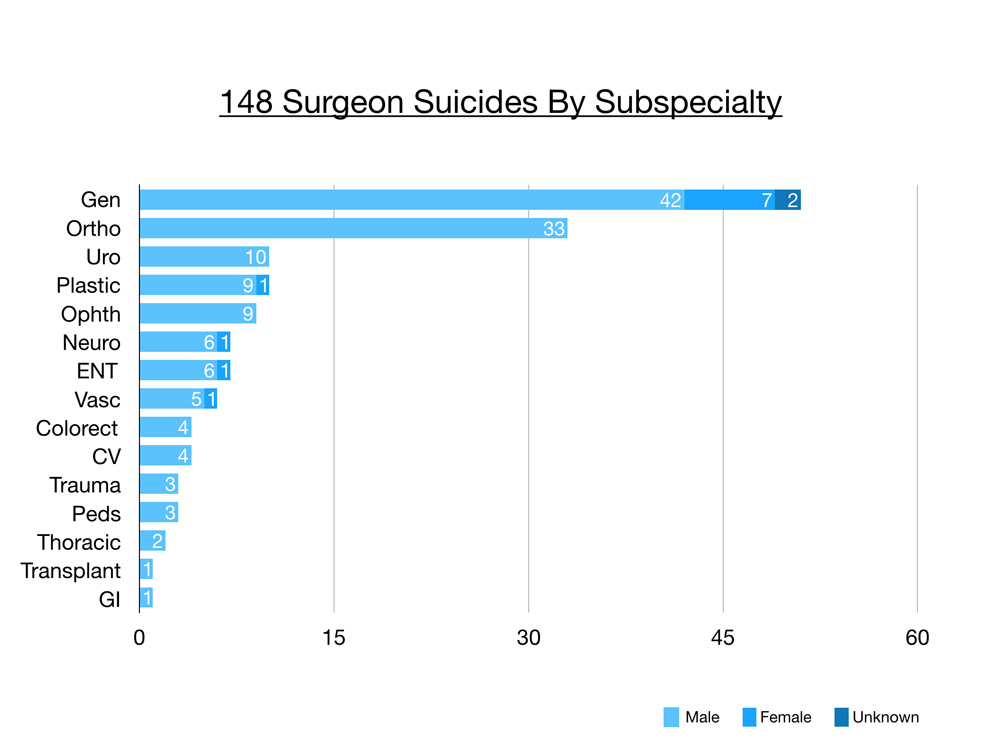

Raw numbers from my registry reveal general surgeons at 51, orthopaedic surgeons at 33, then urology and plastic surgery with 10 cases each, ophthalmology with nine, neurosurgery and ENT with seven, vascular six, and so on. Several of these surgical subspecialties only have a few thousand active practicing physicians and so the sample size is quite small and it does make it more challenging to analyze and reveal trends.

Today I’ll focus on the 33 orthopaedic surgeons we lost to suicide. Why they chose suicide. And what you can do now so that you don’t lose your own life or life of a colleague.

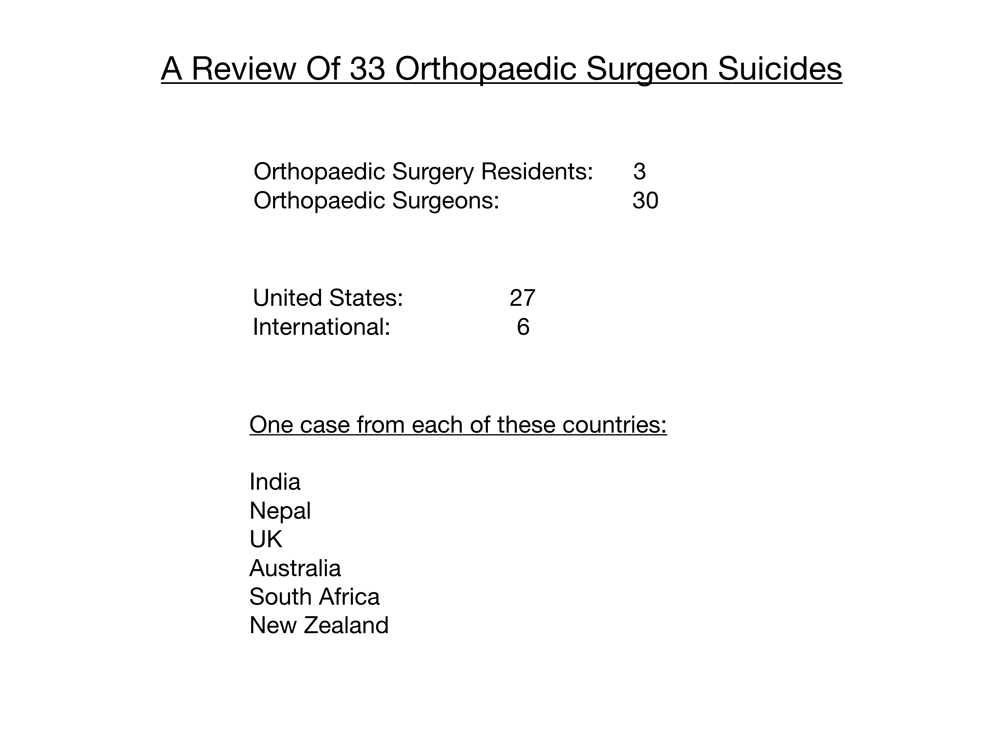

On review of the 33 orthopaedic suicides, 30 were surgeons and three were residents. Again most (27) in the USA and six cases international. One from each of the following countries: India, Nepal, UK, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand.

These numbers are the tip of the iceberg. I certainly do not have a comprehensive list, nor does anyone on the planet. Many doctor suicides are well hidden for a variety of reasons, stigma within society, the medical system, even families (who have asked me to lie about the suicides—even when video footage shows the doctor purposefully stepping off the roof of a hospital). Many times even death certificates do not specify suicide (even when there is a suicide note). Doctors may list cause of death on the death certificate as an accident (again for a variety of reasons including reputation of their colleague and life insurance payouts). Some physicians who die by suicide make their death appear to be an accident, again for reputation and life insurance.

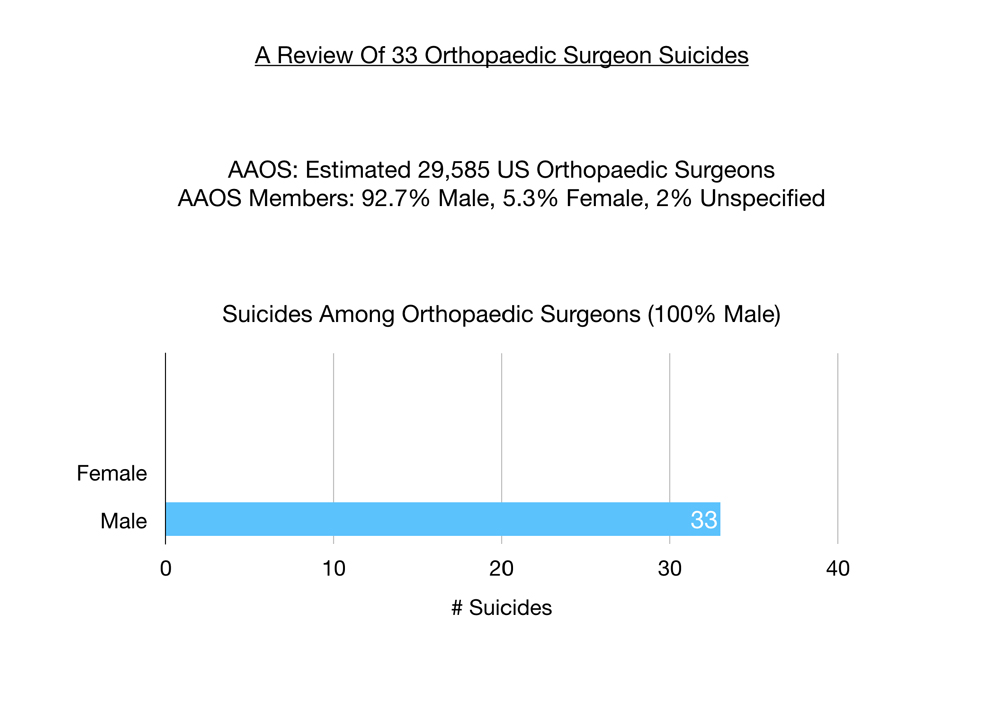

Analyzing these 33 cases of orthopaedic suicides it is not surprising that in a male-dominated specialty (apparently 93% male per AAOS) all 33 orthopaedic surgeon suicides are male.

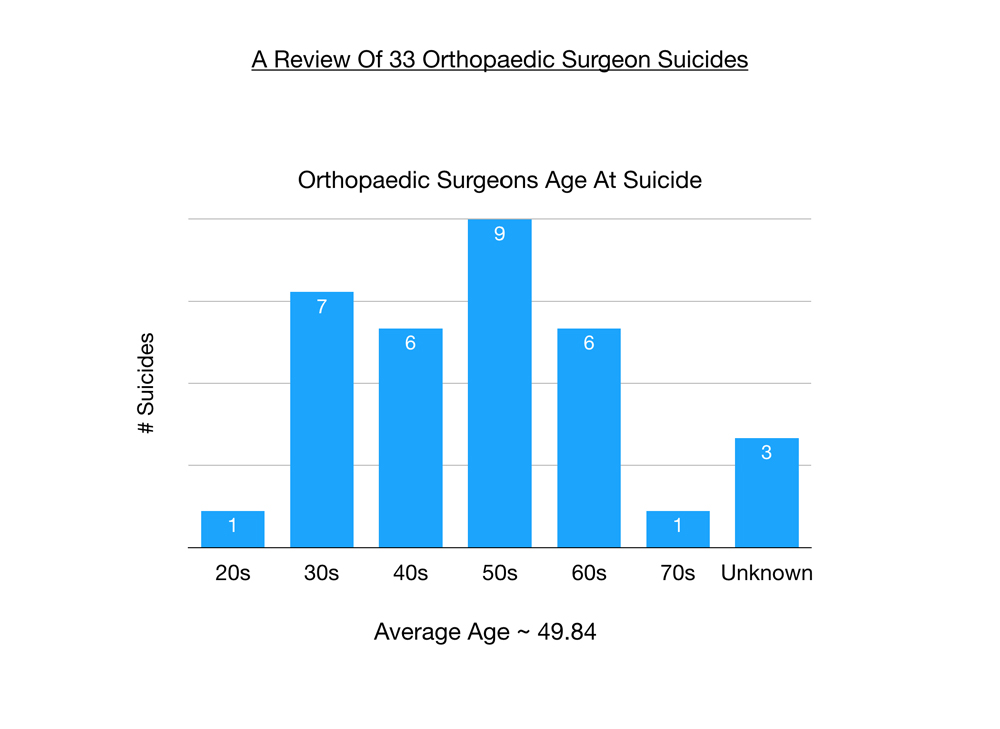

The average age at suicide among these orthopaedic surgeons is 49. Ages range from 25 to 73. Orthopaedic surgeons in their 50s tend to be a high-risk age group.

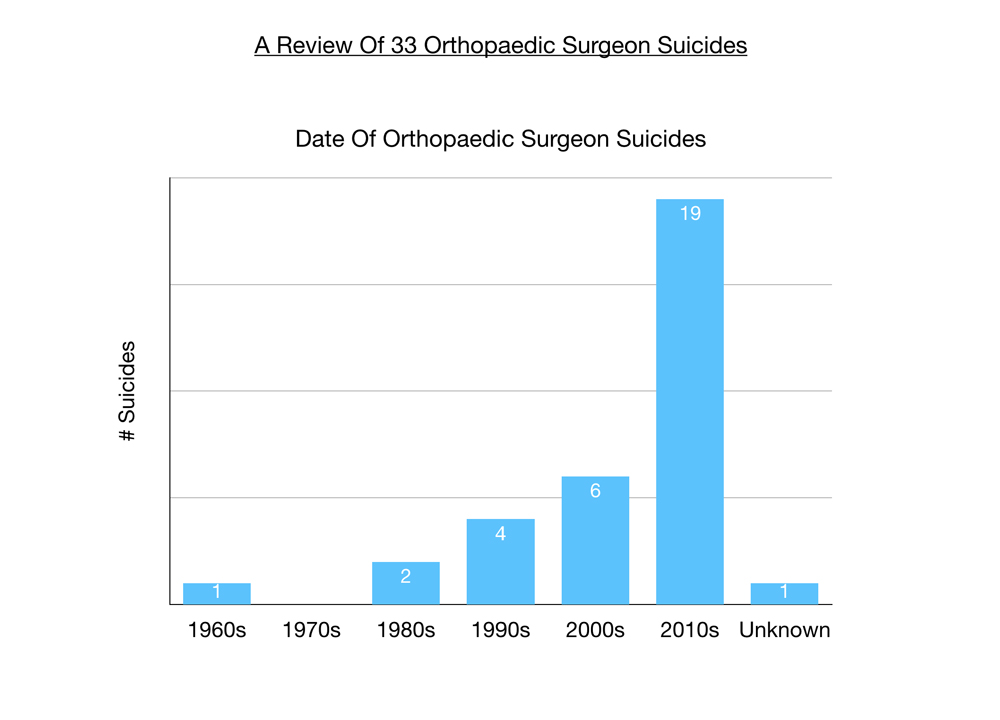

The majority of these suicides were in the last 10 years though I recently discovered one from the 1960s in my hometown.

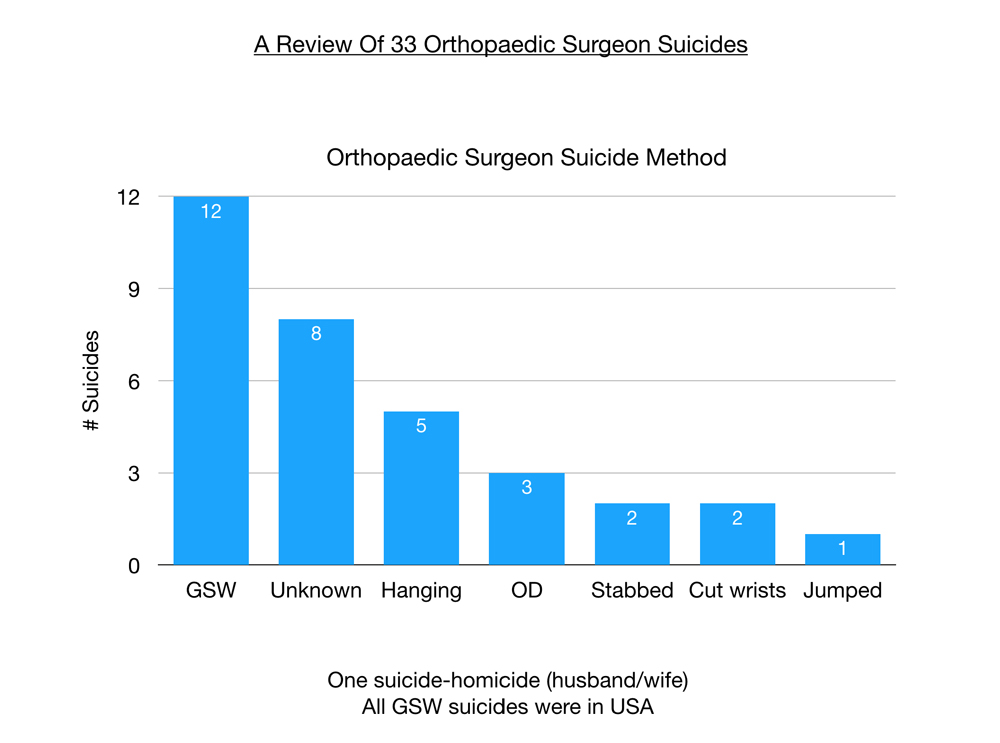

Most popular method of suicide among orthopaedic surgeons is gunshot wounds in the USA. Then hanging and overdose (these dominate overseas). Due to the taboo nature of suicide, eight of the cases reported to me by friends and colleagues have unknown method of suicide. A unique method for physicians (very uncommon in other populations) is stabbing oneself to death.

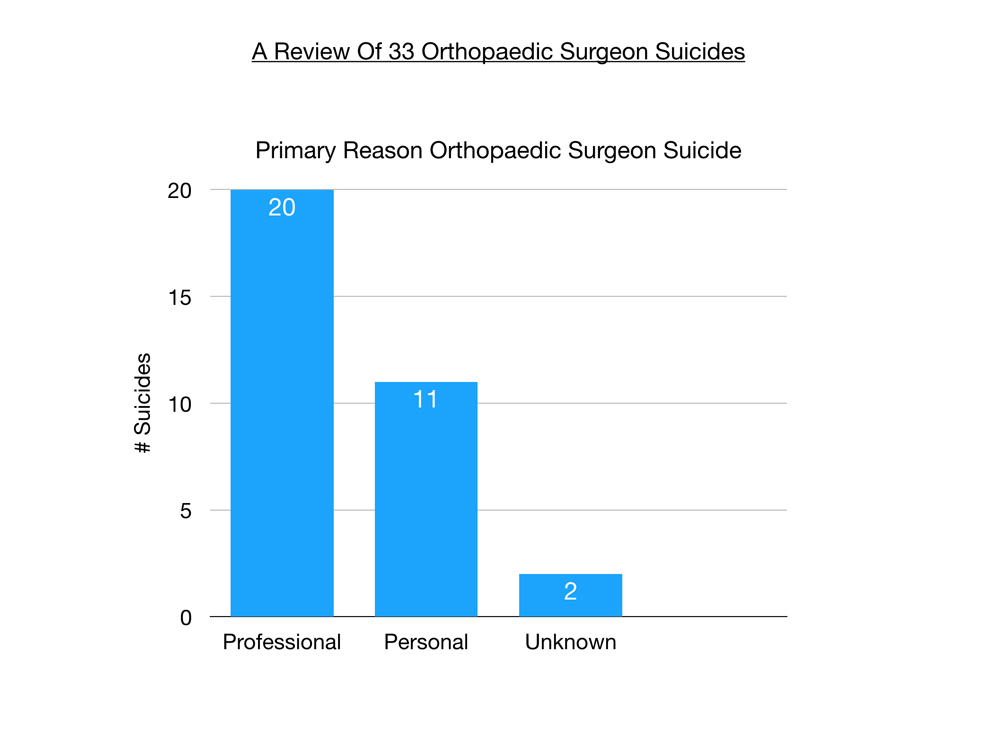

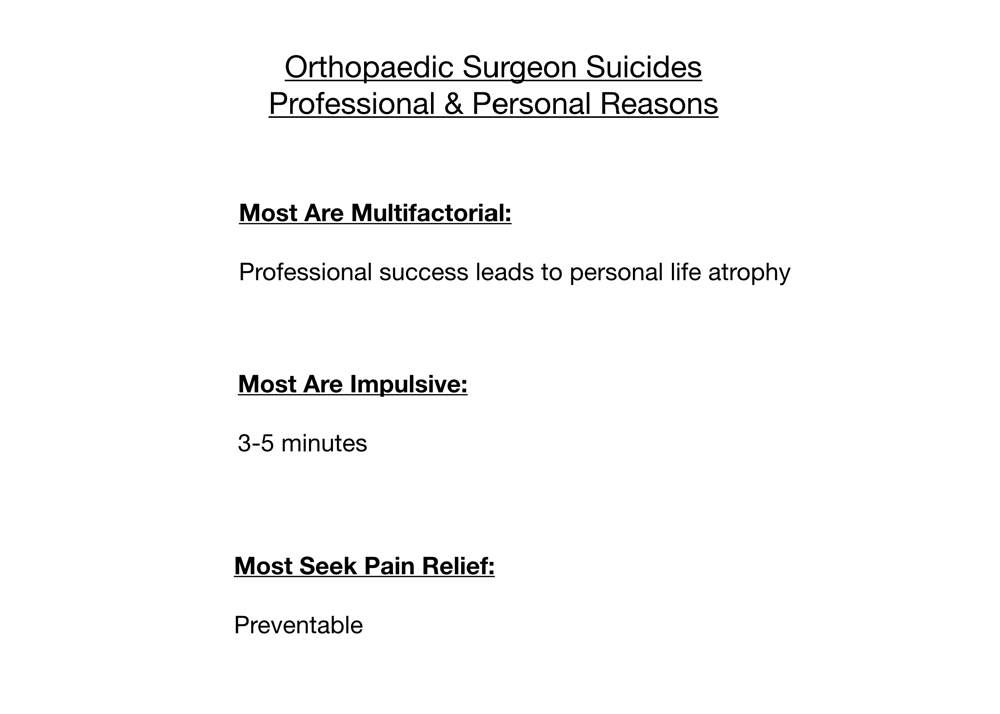

Of greatest interest to me are the reasons why doctors kill themselves. Most suicides are multifactorial, a series of events that unfold in the months leading up to the suicide. In categorizing these suicides, I was interested in the one factor at the end that made life so intolerable that these physicians saw no other way out. For orthopaedic surgeons, most are choosing suicide due to professional, not personal reasons.

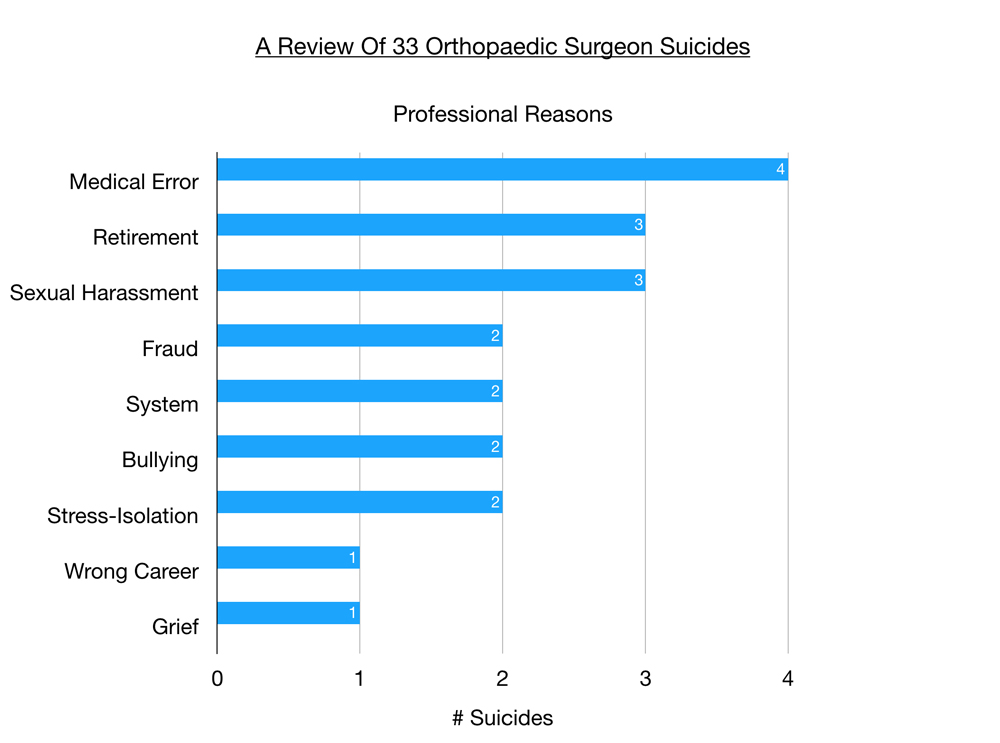

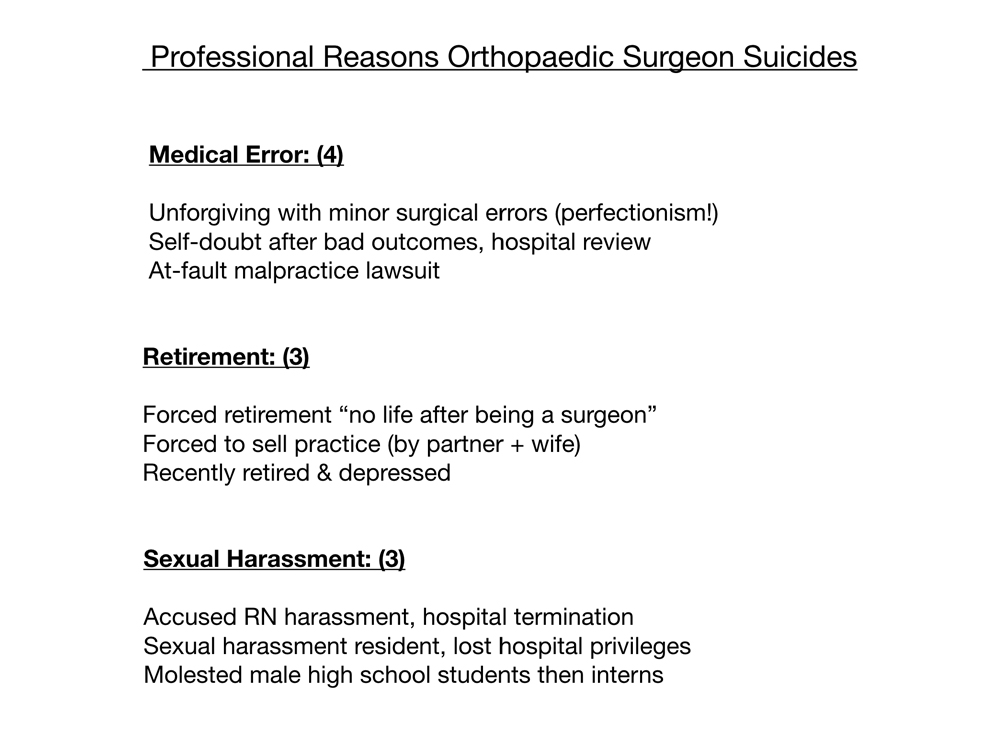

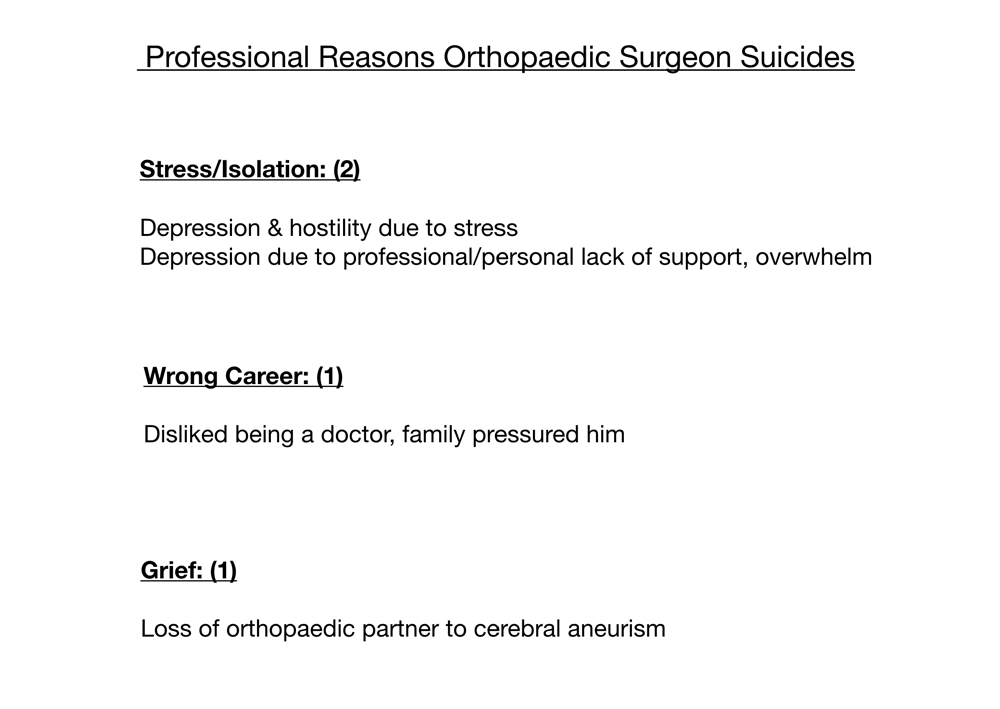

In order of significance, are medical errors, retirement, sexual harassment (and repercussions like loss of hospital privileges), fraud, the system, bullying, stress & isolation, wrong career, and grief after sudden death of orthopaedic partner.

In order of significance, are medical errors, retirement, sexual harassment (and repercussions like loss of hospital privileges), fraud, the system, bullying, stress & isolation, wrong career, and grief after sudden death of orthopaedic partner.

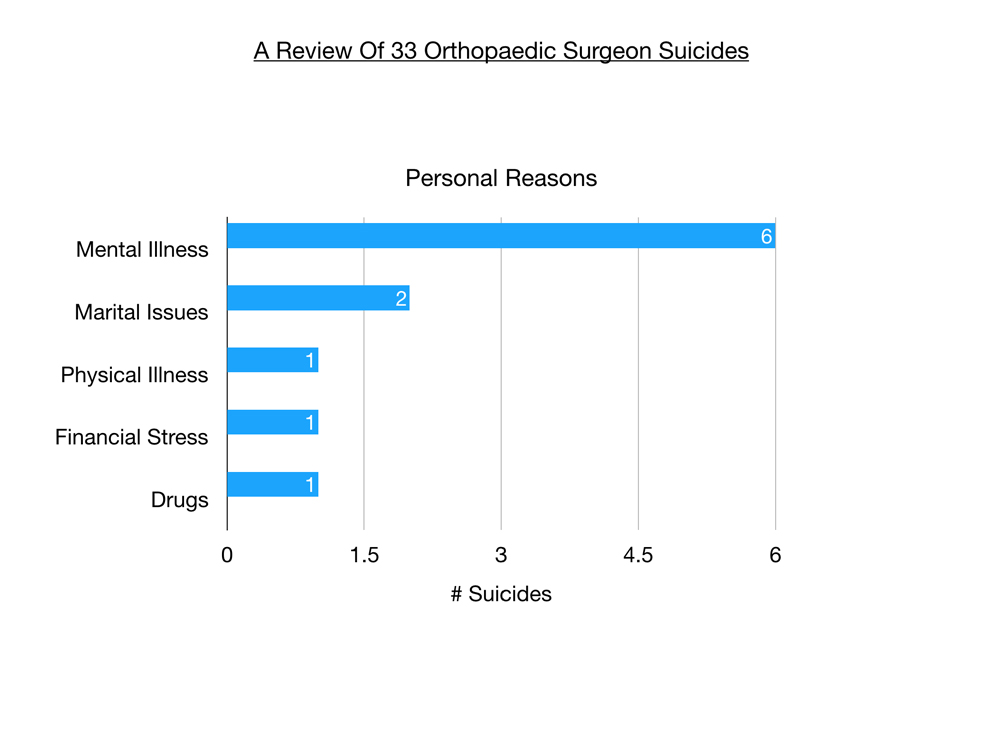

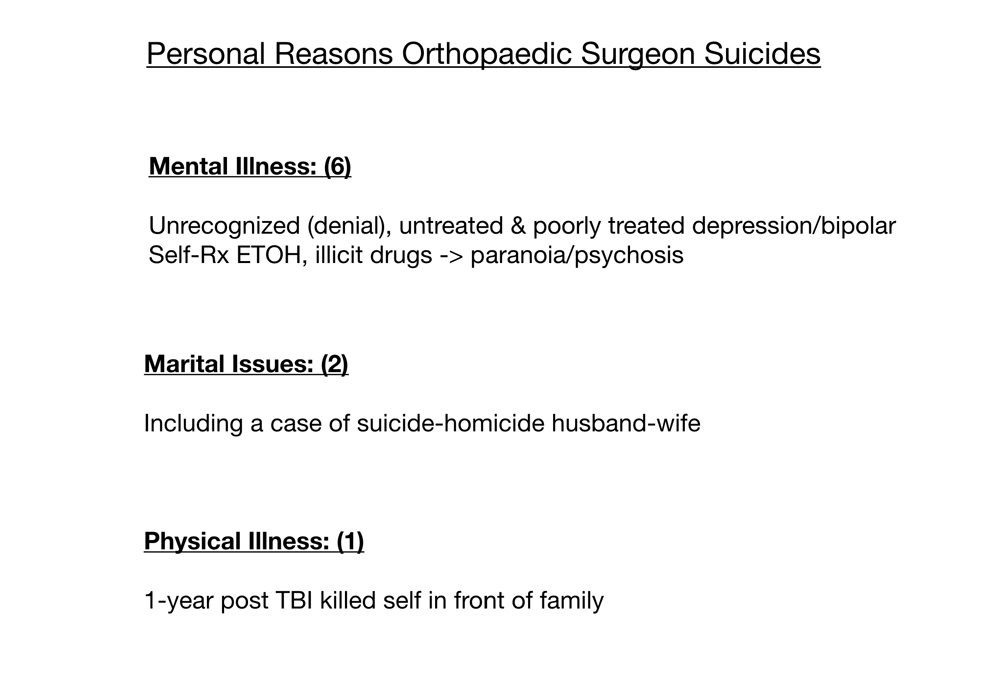

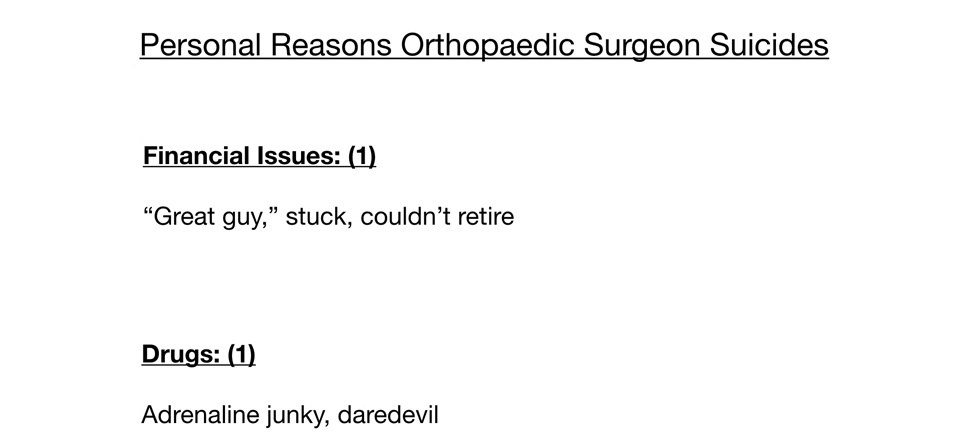

Personal reasons include mental illness, marital issues, physical illness, financial distress, and drugs.

Top professional reason for orthopaedic surgeons choosing suicide is medical errors. Perfectionism leading to self-loathing for even minor surgical errors, self doubt after bad outcomes on knee replacements with pending hospital review, and one case involving an at-fault malpractice suit.

Top professional reason for orthopaedic surgeons choosing suicide is medical errors. Perfectionism leading to self-loathing for even minor surgical errors, self doubt after bad outcomes on knee replacements with pending hospital review, and one case involving an at-fault malpractice suit.

Next we have retirement and sexual harassment with three cases in each category. Forced retirement due to age, pressure from wife and partner to sell to hospital. When one’s identity is so wrapped up in an all-consuming career like orthopaedic surgery, who are you when you retire? Many times we are alienated emotionally from our spouse after years of working excessively and there is a risk that retirement can unearth failing marital relationships. Retirement can lead to boredom and a feeling of uselessness.

Sexual harassment as a precipitant to suicide among orthopaedic surgeons came as a complete shock to me. Sexual harassment, of course, can span the gamut from comments objectifying or sexualizing staff and other physicians to unwanted physical contact to even molesting male high school students and interns over decades. Obviously in that last case (after the police raided his home) he was heading for prison time. In the other two cases I do not have the specific details but these appear to be accusations of verbal harassment of female staff. In one case a young new surgeon wanted to date an RN and was persistent about it. She reported him for sexual harassment. The hospital consulted with their legal team that recommended he be terminated and he went home and shot himself.

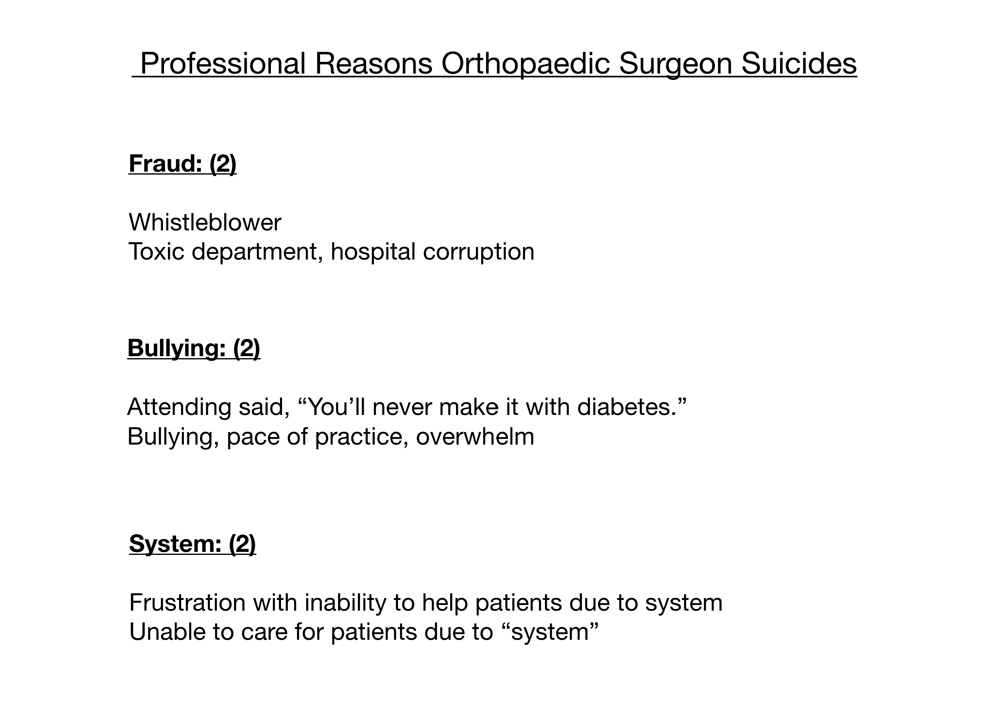

Next is fraud—witnessing hospital corruption, becoming involved in a toxic department in which there is criminal activity, and feeling pressured to participate in medical care that you deem unethical, unnecessary, or even criminal.

Bullying is known to lead to suicides in middle school and high school. Bullying also is more common that we’d like to acknowledge in our residency training. One female physician told me her boyfriend from medical school was accepted into a highly-coveted orthopaedic residency. He had type 1 diabetes. Just weeks into his intern year his attending told him: “You’ll never make it with diabetes.” He went home and shot himself in the head. Others report years of ongoing subtle bullying on top of all the other stressors of practice.

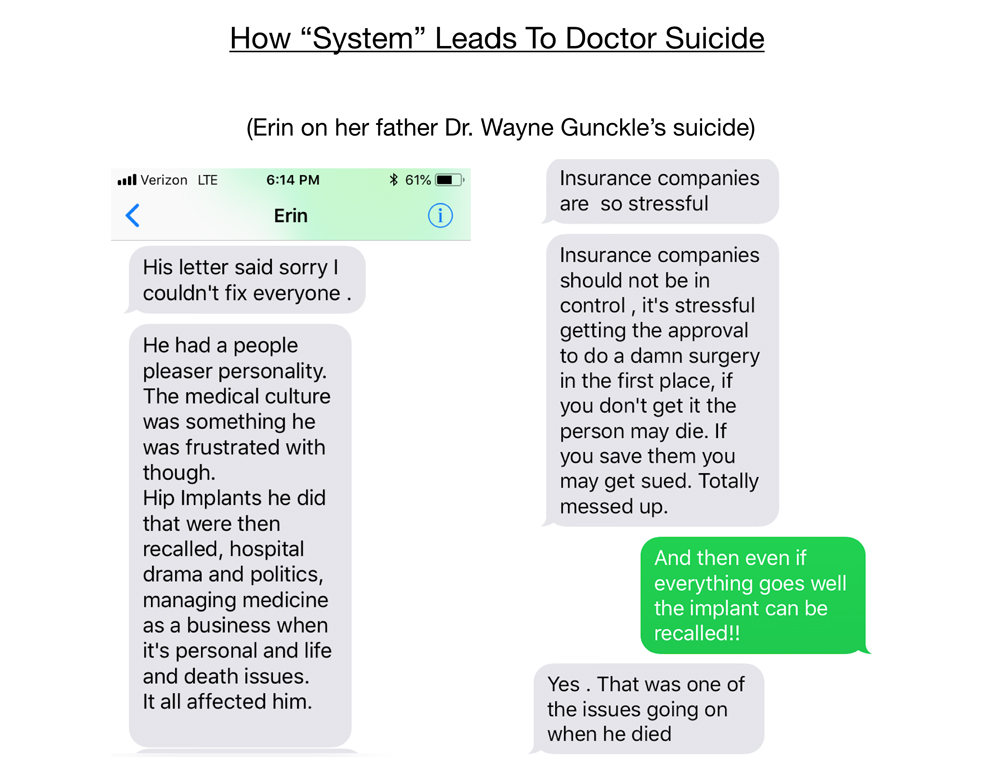

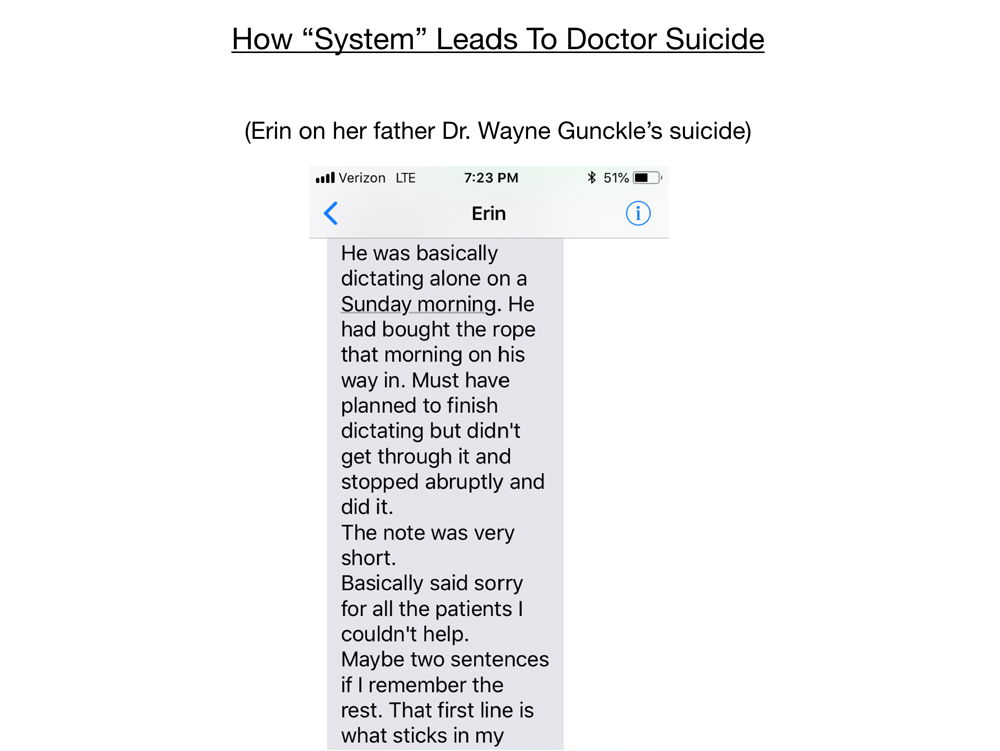

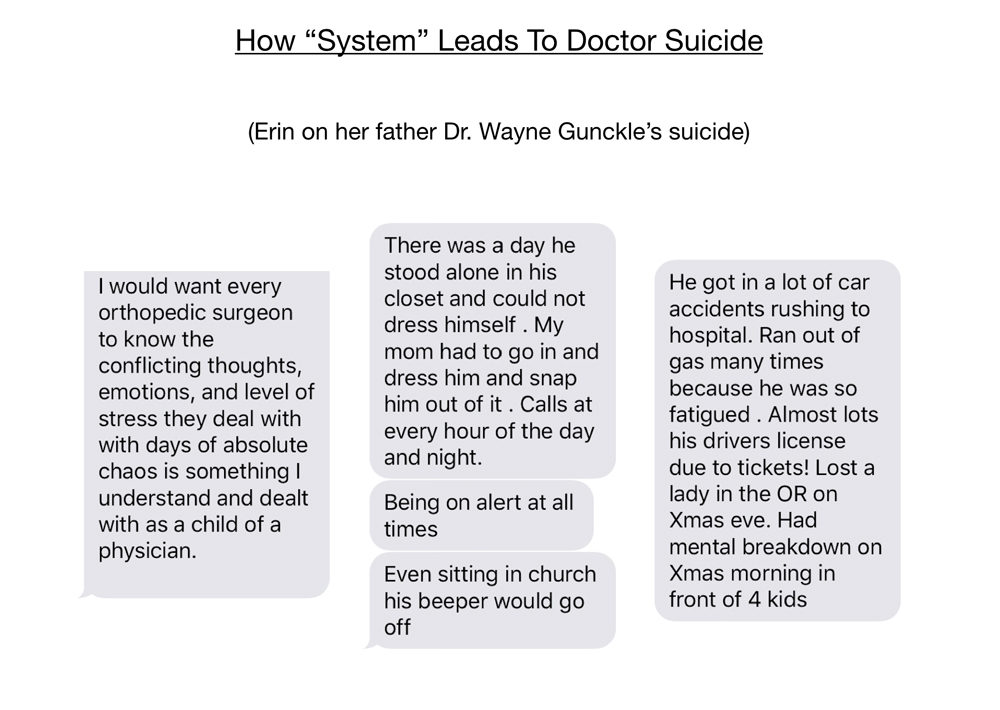

The “system” includes insurance hassles, hospital politics, and even the stresses of being a business owner or an employee (unique frustration with each). To elaborate, I’ll share a conversation I had with Erin Gunckle regarding her father Dr. Wayne Gunckle, an orthopaedic surgeon who died in 2011.

As his daughter reports: “It’s stressful getting the approval to do a damn surgery in the first place. If you don’t get it the patient may die. If you save them you may get sued. And if everything goes well the implant may be recalled. That’s what was going on when he died.”

So on 3/27/2011, Wayne bought a rope on his way into the office Sunday morning. He had planned to finish dictating his charts before his suicide, but stopped abruptly and hung himself.

He left a suicide note: “I’m sorry I couldn’t fix everyone.”

The lack of support and sheer overwhelm take an emotional toll on all of us over time. Erin writes: “There was a day when he stood alone in his closet and could not dress himself. My mom had to go in and dress him and snap him out of it. Being on alert at all times. Even sitting in church his beeper would go off. He got in a lot of car accidents rushing to the hospital. Ran out of gas many times because he was so fatigued. Almost lost his driver’s license due to tickets. Lost a lady in the OR on Christmas eve. Had a mental breakdown on Christmas morning in front of four kids.”

Continuing with the professional reasons for suicides: It’s not a surprise that orthopaedic surgeons would suffer from stress and isolation leading to overwhelm. Some then suffer from depression and even hostility. One felt pressured by family to pursue medicine and was in the wrong career. And the one that I recently investigated in my town died in part due to a grief reaction. In 1996 an iconic orthopedic surgeon died suddenly by cerebral aneurysm, weeks later his only partner died by suicide.

Mental illness tops the list of personal reasons. Six cases of either unrecognized (denial), untreated, poorly treated depression or bipolar. Sometimes doctors self-treat with alcohol, stimulants, and other illicit drugs eventually leading to paranoia and psychosis. Stigma prevents doctors from seeking treatment.

Marital issues, pending divorce, including a case of husband-wife suicide-homicide. Do you realize there is a Facebook group for wives of doctors in domestic violence relationships? The predictable end result of not being proactive in caring for these highly stressed individuals who fear seeking mental health help.

One surgeon with traumatic brain injury killed himself in front of his family.

Additionally, one orthopaedic surgeon had financial issues, was unable to retire and felt trapped. Another had what appeared to be a drug problem.

Most are multifactorial. Professional success often leads to personal life atrophy. So it is challenging to isolate just one component as the central cause as many of these victims had chronic issues that were brewing and neglected for years. The good news is that gives us a lot more time to intervene to help prevent future suicides.

Most suicides are impulsive. I interviewed several male physicians who (against all odds) survived their suicides. I asked, “How long after you decided to die by suicide did you take the pills or slice your artery?” Answer: three to five minutes. Again, though the final decision took less than five minutes to carry out, the underlying issues that led to that decision to die by suicide had been present for years to decades.

The reason why most die by suicide is for emotional pain relief. In absence of support the only way they know in the moment to get out of the pain is suicide.

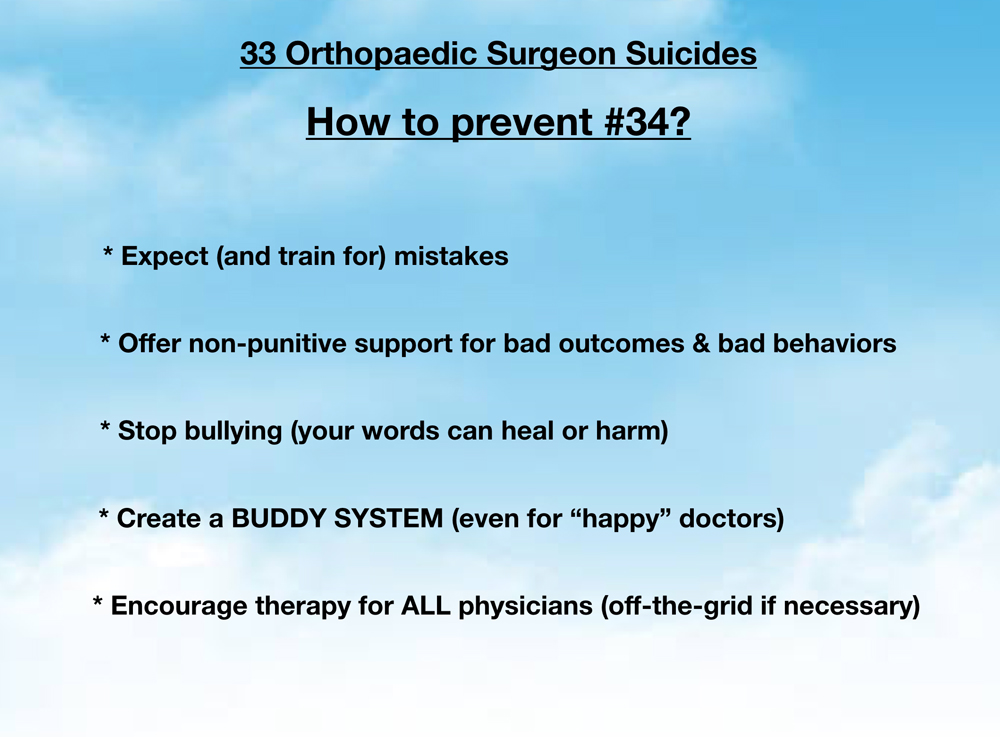

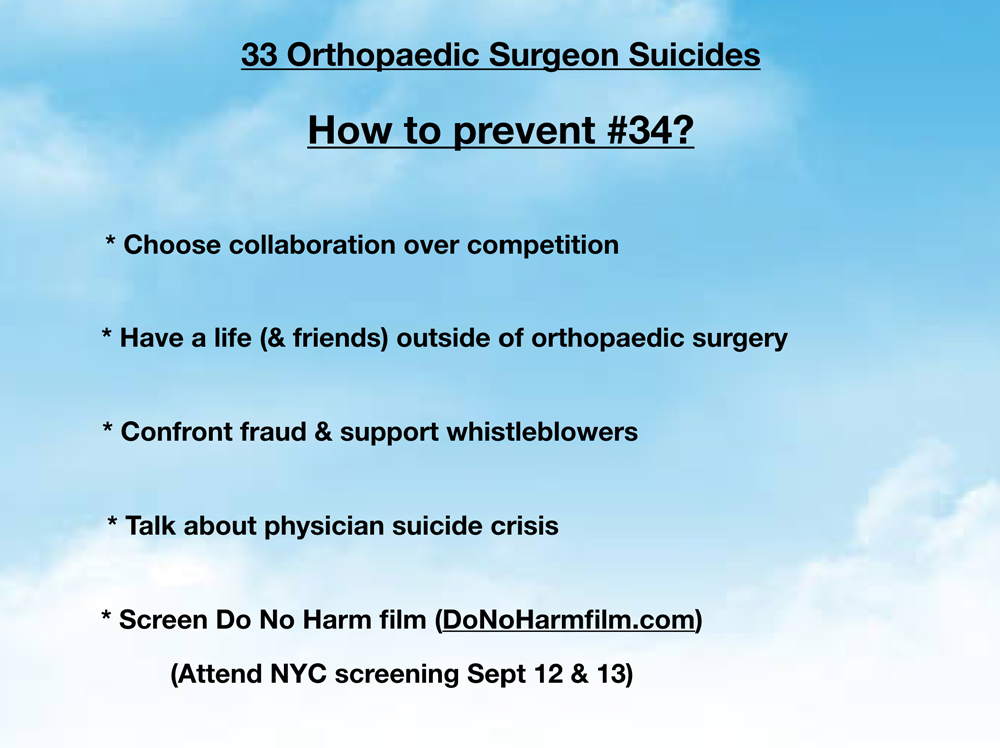

In conclusion, here are very simple no/low-cost solutions that can be adopted immediately to prevent suicides specifically among orthopaedic surgeons. You are more than your craft. Doctors are human. We require emotional support to thrive in medicine. The culture of medical education has too often pitted us against one another in an environment in which your success depends on crushing your competition. What if we interacted as human beings first? I invite you to embrace each other as brothers and sisters in medicine.

Even perfectionists make mistakes. The stakes are incredibly high and mistakes are inevitable when working on the mechanics of the human body. Expect (and train for) medical errors. Orthopaedic surgeons are taught like mechanics. Your personal and mental health needs may be least attended to compared with other specialties like family medicine.

Offer non-punitive support for bad outcomes and bad behaviors. First do no harm to yourself and your colleagues. Doctor means teacher. Use words that heal and above all do not injure other people. Often those who are injuring others have been injured themselves in medical training. As they say, “Hurt people hurt people.”Medical institutions should be safe spaces—free of bullying, sexual harassment, and public humiliation. A cycle of abuse involves perpetrators, victims, and witnesses. We can all actively stop this cycle in a way that helps everyone heal without losing any more lives.

Reach out. Take my challenge to get to know each other personally—not just professionally. Assume “happy” doctors are suffering silently. Create a buddy system—even informally. Pair up with a colleague and go to lunch once a week. Talk about more than sports, RVUs, and complex tibial plateau fractures (in less than 10 minutes!). Really talk (for maybe an hour) about how you are feeling—about your life. Know that there are counselors, therapists, psychiatrists who have practices dedicated to solely serving physicians and our special needs. (Yes, as a surgeon you are in a special needs group). Schedule regular sessions (even by Skype/phone, off-the-grid if necessary). You are not alone. You are welcome to contact me 24/7.

We need to talk about the tough things—fraud, corruption, and suicide. Support whistle blowers, depressed and suicidal physicians. Share your emotional struggles openly so that others feel safe to open up to you. Don’t just “go with the flow” and pretend like everything is okay. It’s not. We have the highest suicide rate of any profession. You can be a lifeline for those who are at the end of their rope.

Do No Harm—is an award-winning documentary by Emmy-winning filmmaker, Robyn Symon. A four-year project just completed this summer that honors nearly 100 doctors who have died by suicide including Ben Shaffer, Steve Ortiz, and Wayne Gunckle. Now screening at hospitals, medical schools and conferences. Attend NYC screening on September 12 & 13. Panel discussion to follow. I’ll be there and would love to see you. Grab your tickets here.

I’m open for questions. Download your free audiobook of Physician Suicide Letters—Answered. Most letters are from physicians on the edge debating whether to live or die. Most decided to stay on the planet with us. Most of these orthopaedic surgeons who died by suicide would have wanted to have a different ending. We have a lot to learn from them. Thank you.

Have you lost a doctor or medical student in your life to suicide? Please add their name to registry here.

This is all very sad. I am a retired UK clinical psychologist with 30 years NHS experience, not one of my 100’s of patients ever killed themselves. I saw patients with all manner of problems referred by their GPs. This meant that some of them asked me to treat their colleagues. We invariably had a few useful sessions. In UK Clinical Psychologists have peer supervision which gives them the opportunity to confide in a trusted colleague about all the difficulties encountered professionally, personally and at work. I think your recommendation to make these relationships is one of the most useful ones you make. I hope you have an opportunity to consult a colleague yourself.

That’s a great track record? Did you lose any physicians in the UK that you knew to suicide?

Reading this brought tears to my eyes. I’m the mother of Dr. Ortiz (talked about in the presentation). Oh, how I wish he had known of Dr. Wible and the help he could have gotten.

If any physicians, residents, med schools students or hospital personnel reading this article have a need for help due to stress, overwork, bullying, please seek help, it’s out there and it can start with Dr. Pamela Wible.

There are so many people who care but they can’t help if they don’t know about you!

Hi Gloria. This was just brought to my attention. I am the nurse he contacted before he left this earth. He was a great friend and physician and is truly missed every day even after all this time. So sad that we weren’t able to stop this from happening to him and so many others.

I was the nurse that Steve emailed before taking his life. His death was a devastating blow to our community. I am sad that he felt that was his only way out. We still talk about him a lot when we are working. I hate that this is such a big issue for people who dedicate their lives to helping others. He was a decimated and caring physician.

My father was a physician and took his life 40 years ago on Dec 7, 1978. If you want more information, don’t hesitate to contact me. Honestly did not read the whole article because it still is very painful, yet I would be more than willing to share details if it will help with research and provide more recommendations on how we can better support physicians so this stops.

It would absolutely help. Emailing you now.

Hi Pamela;

Thank you for all you are doing for physicians who have or are contemplating suicide.

I am one of these physicians and , because of this, left my medical practice 18 years ago.

I would like to speak with you about the issues . How do I contact you ?

CE Moon, MD

https://www.idealmedicalcare.org/contact/ Happy to talk . . .

Superb Work Pamela.

Congratulation!

I do not know anyone else doing something like this.

Labor of love for my brothers & sisters in medicine. I could have been one of my statistics. Thankful that I’m alive to bring my comrades back to life—at least in print & now in film. There is a “Wall of Remembrance” in the documentary with nearly 100 suicided doctors who are honored for their contributions to medicine (kind of like a Vietnam Memorial for doctors). View movie trailer here: http://donoharmfilm.com

Hello, I managed the trauma program. A general/vascular/trauma surgeon that I worked with in San Angelo, TX commited suicide in 2013 – Patrick Gibson, MD. There was another surgeon (his partner) that also committed suicide in ~2009. Thank you for addressing mental health crisis/issues in healthcare. I was hired to come in and revive their trauma program after his death and didn’t know until after I’d gotten there that he’d commit suicide. His name was 2009 David Saborio, MD. Shot himself in the head in a local park. Pat or “Gibby”, as we called him shot himself in the same way in the same park. When I learned this, I asked if they were investigating since two surgeons died that way both from the same toxic hospital which had numerous leadership turnovers. I know he also had a lot of professional pressure. He was the only general surgeon for a long time for this hospital. There was one other hospital in town. But San Angelo is hours from larger cities and higher levels of care. There had been 3 surgeons in his practice. The oldest one was primarily retired. Then Saborio commit suicide and left only Gibson. When I got there to work with them to get the trauma designation back for the hospital, it was a lot for him. The retired surgeon would take call one weekend a month or so to give him a break. Then that surgeon dropped dead of a heart attack. Gibby was there, they were all watching grandkids play a basketball game, gave him CPR until medics arrived but he didn’t make it, they pronounced him in ED. As soon as I got word the next morning I went and found him as he was coming out of the OR to give my condolences. I’ll never forget how he laid his head on my shoulder and cried. He said “my partners keep dying on me.” A few months later they hired a new surgeon who was fresh out of residency. We were able to get the trauma designation back, then I resigned shortly after that. From what I was told they struggled again to keep leadership for the program and keep the designation. Gibby also told me that the surgeon didn’t stay (her military husband was transferred) so he was alone again, I don’t know for how long. He was one of the few people I stayed in touch with after leaving there. The last time I spoke with him, he was celebrating the birth of a new grand baby. I’m still heart broken over him being gone.

Wow. I’m seeing there are clusters now in certain hospitals and residencies. Just reading the last few comments. Two in the same park? We actually had more than one doc die in the same park too. Similar locations to the point where the medical society director was concerned that it was a hot spot for doc suicides. Unreal.

Will send you Pat Gibson’s obituary. It includes a lot of details but suicide is not mentioned.

3 Residents within the U of M residency programs have committed suicide in the last 3 months. Where is the outrage at the medical training system!? Demand answers from the people in charge of these programs. MN Daily found it pertinent to run an article on a study which showed a possible increase in suicidal thoughts within the LGBT acne community in 2017, thats right, the LGBT acne community. But when residents are killing themselves right under your noses you are silent! Demand answers and actual change, offering counselors and forums as a solution is comically deficient in addressing the real systematic problem. Residents and medical students are put under immense pressure and at any point in their pursuit they can be cut off due to any number of reasons (test scores, poor performance, health reasons). Demanding perfection of people for a decade is an unreasonable expectation. The university needs to offer exceptional resources and they need to let the residents know, no matter what happens the university has their back and will support them through tough times. Hiding physician suicides is common and an outrage. Mn daily needs to do their part in exposing the broken medical training system that demands too much from people and the consequences are dire!

Systemic issue and occupationally-induced especially with 3 in one hospital in 3 months! Root cause analysis points to medical education human rights violations of our doctors-in-training. Are these in the same residency program? Complex situation and many programs far worse than others. Thank you for speaking up. I’m heartbroken. Please send me the names as I want to make sure they are represented on the registry.

We need to go back to a balance of life and work that we used to have in the 1950s and 1960s before HMOs and business leaders took over the medical field.

Why are we not charging the CEOs, their fellow doctors and nurses with murder who cause these doctors’ deaths because they were bullying these doctors and creating slavery-like working conditions?

Thank you for bringing this to light, all you do, & being of service in this way. I am in the military part time and a wonderful physician colleague (family doc) and of course the happiest and sweetest man you’d ever meet also in the military, who treated everyone has an equal, but later found out had deep struggles with marriage and balancing his commitments and he committed suicide by hanging 2/4/17. From my own experience, it’s a challenge for those who want to be physicians or other medical providers as it’s a calling and devotion to your patients and others who don’t have that same drive& devotion to be healers like perhaps spouses or partners, they often times in their desire for a more balanced home life put further undue pressures and criticality on their spouse physicians, as not only there’s daily long hours but throw in deployments. (It’s a double ‘being of service’ whammy) that really beats up a stable home life. I would imagine military physicians are up there on suicides (and/or going ballistic overseas). Again, keep up the amazing work and I hope to attend a retreat to get my own biz off the ground doing what I love!

I want to make sure he’s on the registry. I’ll email you. So very sorry Diana. Military docs get kinds of a double whammy.

What an astonishing and astonishing sad and tragic presentation Pamela.

So glad that you are bringing this out into the open.

We’ve been in touch before and as you know I was a boots on the ground suicide specializing psychiatrist for many years, mentored by Dr. Edwin Shneidman, a pioneer in the study of suicide.

Here is a link to an infographic called the Road Back from Hell that I have been using with vets and active military. It has helped them by giving them a vocabulary to express what they feel, the doing of which seems to help.

Something that I am discovering with military that perhaps some of your doctors who are depressed and feeling suicidal might relate to is feeling not in control = feeling out of control and following that, the next step is feeling they will literally fall apart and shatter and never come back and always be a burden.

So at that point they kill themselves to avoid that.

BTW this is also the point where many vets are looking down the barrel of a gun and discover God. In a number of cases they are able to “surrender” to God and that allows them to short circuit or bypass the “not in control –> out of control” beginning of the death spiral.

And then something paradoxical happens. Instead of coming apart, they let go of control, lean into their faith, cry with relief and then slowly begin to come back to their senses.

You’ll get a sense of how faith can rescue people if you read the transcript of Brian Dawkins NFL Hall of Fame induction speech.

I believe that if we have groups of physicians sharing their feelings along the Road Back from Hell journey as vets are doing, this can help them get their feelings out, lessen the isolation (where you’re more prey to your imagination) and they will be able to lean into the shared humanity and vulnerability they are all feeling.

I’m also listing an article I wrote as my website entitled: Why people kill themselves. It’s not depression.

God bless you for this work Pamela.

Should be “astonishingly sad”

Doctor just told me: “I know of several colleagues. A plastic surgeon. A neuro-ophthalmologist, A Gynecologist. A Medical student + Several ” could be’s ”

For those who want to submit names to confidential registry please include: For registry I collect specialty, age at death, date of death, location, and any other circumstances you

wish to share (which I shall keep confidential).

One thing I would like to know from the physicians who considered suicide and did not follow through: What kept you alive? What kept you going? Perhaps this will give the rest of us clues as to how we can reach out and prevent further losses.

For myself I can say that I was in bed 6 weeks praying to die in my sleep and not wake up in the morning. I felt like I was in a depressive coma or something. What kept me alive is 1) I’m not a violent person (so no gun and no desire to do anything violent – overdose would have been my method for sure) 2) I was SO depressed I couldn’t even think straight to plan anything so what kept me alive is that it is very uncommon for a healthy vegetarian woman to die in her sleep at age 36.

As for others, I have heard it’s their kids that keep them going. One told me it was the dog. Feeling like you had someone depending on you kept some going. Download free audiobook (Physician Suicide Letters—Answered) as 53 docs share their feelings and reasoning for dying or staying when on the edge.

I was at a very low point in medical school, having requested a second non-consecutive year leave of absence, which the main Dean of the school responded to by advising the promotions committee to ask me to withdraw (a euphemism for being kicked out).

The Dean of Students, who to this day I believe was an angel sent to earth to save my life, delivered the bad news to me and before I descended further towards suicide, he stepped in, saw value and a future for me – that I didn’t see – based on some ability to care he saw in me that wasn’t graded in med school and then took on the medical school and its Dean to appeal their decision at his own expense.

When an angel steps into your life and saves it, you’re never the same again, but it compels you to pay it forward which is why I became a suicide specialist who intervened with people as he did with me, rather than studying it as an academic. That explains my challenges in getting through to the medical establishment with my non-evidence based approaches.

Pamela, once again you continue to amaze me! You so eloquently deliver sensitively an uncomfortable topic that needs to be discussed in medicine today. Since knowing you, I now see physicians in a new light and realize all the pressures they have endured to continue caring for their patients. It is time for the healthcare system and medical administration culture to change from demanding more from physicians and instead provide the support these healers need to heal their patients and themselves. Thank you for your passion and dedication.

Im sure you were made aware of this Canadian Medical student who did not match to a residency program 2 years in a row. Debt, shame and societal pressure ultimately led him to take his own life.

Robert Chu MD

Yes. He is on the registry. I’ve spoken to his father. His photo is actually up in my house and he is going to be featured in the forthcoming film. Please view trailer here and come on out to a screening this fall: http://donoharmfilm.com

Matt Levin, MD here in Western PA

We’ve talked a couple of times and I gave “testimonial” about your first book the Goats, etc.

Sorry can’t get away midweek for your NYC present but look forward to your future work.

As a solo for 15 years, and treating several physicians for GAD, etc, I am pleased to see you making progress.

I am sure you are aware of the academic work on “burnout” a Stanford group is doing, as you were quoted in the Medscape article.

I would be pleased to be an “east coast resource” for suicide outreach if I can help.

Please let me know through email if I can be of further assistance.

Like you I am solo, and I like it that way….

Take care,

Dr Matthew Levin

I won’t put an email down here as medical needs should go through the office.

PS Yes I lost a professional friend to suicide by GSW; the “system” still has his name on the sign in front of the building I pass almost every day – it’s been 3 years now.

“very enlightening article. i am an orthopedic surgeon as well from the philippines. just like to share but i dont want my name or email written in the comment section. i have thought about these things too. like wishing the plane im on to crash or drive my car off the cliff. the worst is i see or imagine myself sitting on the bed with the gun in my mouth. medical practice is tough in my place. i can work 24/7 without complaint. if it is just the bulk of surgery as long as the materials are provided. the thing is that due to lack of manpower and resources, patient care and surgery is delayed which puts the patient at high risk for complications and us doctors for liabilities and public shaming. added factors are: i live alone in that workplace away from my family which i only get to see once a month (if i get lucky) or once in 3months. it has been 10 years that i havent spent christmas holidays with my family as i was always on duty for those days. we always postpone christmas and new year. my workplace is 380km away from our home. there were even times that i feel numb towards my patients…. at the back of my mind “there must be something more to life than this… i cant keep going on like this…” i felt trapped in a loop. eventually, i resigned. now im doing fellowship and feeling better. as to what comes next, still uncertain….”

have a few thoughts about anesthesiologist: first, they have ready access to lethal drugs and are skilled enough to be successful. Second, their workday is a lot like an air traffic controller’s, busy at the beginning and end of a case and mostly boring on the middle but they can’t leave their seat, then occasional episodes of pure terror. Third, they get blamed by the more glamorous and better paid (?) surgeons a lot. Time everyday to ruminate on and obsess over perceived failures. Also their schedules are completely tied to the surgeons’ schedules.The ones I know are also extra sensitive to pt pain and pain management lives in anesthesia in my institution, and they seem to feel patients’ pain more than other surgical people.

Have you noted any pattern at certain institutions? I started residency in California. I ended up at Mt. Sinai in NYC. It was like night and day. While my previous program was supportive and nurturimg during one of the hardest parts or our careers—sinai was horrible. The environment is so cold and harsh and cut throat. It was so bad that a number of the cheif residents had to be talked in to going to the graduation so the dept wouldn’t look bad. I found out why when i myself felt humiliated when I graduated and the dinner celebration where my family and friends had come across the country for graduation only to have a gruesome “roast” of the cheifs. Residents are routinely criticized and not supported and subtly encouraged to lie about our work hours. I was actually not surprised to hear of a couple of suicides out of Sinai a couple years ago. I was warned it was a “malignant” program and it was. Having had the benefit of a non malignant program i had already had my confidence built up and supported and i knew that was not normal or right- unfortunately most of the other residents had no comparison – so accepted that as normal. I’ve never said anything about this so please do not share my name—but keep an eye on malignant programs that push stressed residents over the edge.

They don’t mention, as a cause, doctors who are falsely accused of things for either Religious reasons (abortion providers being set up by zealous Catholic prosecutors and Heads of OPMC’s), rejecting sexual advances by very mentally ill patients, etc. who later falsely accuse them. The observations seem to focus on the doctors’ personal internal crises and the only mention of external forces relates to Malpractice suits and the stress that causes, or personal home problems. The focus seems to be on the doctor and not really on societal pressures. I spent 2 months in Lawrence, Kansas working with Dr. Richard Irons, author of “The Wounded Healer” and his staff who had over 25 years experience with this issue. Their insight would add greatly to this article.

An hour certainly is not enough time to dive into the magnitude of data I’ve collected and insights gleaned from speaking to thousands of doctors—many injured by the “system” and blamed/shamed in ways that are completely disabling. Sadly. many of us are set up to fail in part due to an artificial cap on the number of physicians leading to shortages (creating a ton of stress on those who remain) and lack of compassionate leadership at our medical institutions that often seem more interested in short-term profit than in the health of their physicians.

I dont think of suicide but I am very depressed. I dont talk about it with anyone, not even my husband because I need to be strong for my family. There are days I feel I am in the wrong profession. There are days I think I dont want to be a doctor anymore. I dont have enough time for my family especially my daughter. I feel like I missed so many things in life because I have dedicated my life to medicine. I try to be strong everyday and face my struggles day by day and try to be happy despite of.

Call me: 541-345-2437 or send a confidential email here and I’ll call you back: https://www.idealmedicalcare.org/contact/

Funny question submitted by a doc:

“Pamela, I was very touched by this piece regarding the orthopaedic surgeon suicides, namely the stories of the two surgeons that you depicted. From looking at the figures breaking down the numbers it appears to me a staggering number of these cases are male. Being a guy who was a star football player tough guy type who is now in medicine (the common sterotype of most Orthos), I am wondering what the best way to get through to them would be? You are undoubtedly the leader and a true hero in this field, but you are what can be conceived as the opposite of the ortho stereotype, a west coast maternal type (no offense intended : ) ). Do these macho guys have a hero in the mental health / physician suicide struggle that looks and talks like them? There was recently a piece on ESPN.com about some prominent NBA players who have been struggling with mental health issues and how few of them talk about it because of the stigma associated with it. A few have come forward however and led the charge, showing that men can be vulnerable and theres nothing wrong with it. These are the people that orthos treat and the tough guys that men look to most often as heroes growing up. If you have an example of a male ‘Pamela equivalent’ that is as passionate about the subject as you are, please let me know, I’m very curious. Thanks again for what you do, you undoubtedly are saving lives every day.”

My response:

“I am happy to help any group of men find the guys among them who can be leaders in this area and facilitate a group that will create culture change in any institution. What I would suggest is a panel discussion (which I like to do after keynotes) in which men will step forward and start to share among each other their struggles and successes within the realm of mental health. I have an example on YouTube – a spontaneous moment during a keynote that demonstrates how your solution is already in the room: Medical school dean talks about losing student to suicide. No need to bring in a Pamela-esque guy from out of town (I don’t really know of any guys like me :). You can harness the champions among you in your organization. . . a west coast maternal type (no offense intended : ) – love it!”

Hi I’m a general surgeon, practicing in Cebu, Philippines. Doctor suicide is rare in the Philippines. I would like to know how we can help… perhaps by comparing.

How to help:

1) Collect data in your country—examine every physician death—especially among younger doctors (and male anesthesiologists)

2) Perform psychological autopsies on all suicides.

3) Show the film in your country at hospitals, clinics, medical schools: http://donoharmfilm.com

Begin the conversation about doctor mental health. Thank you Shawn!

Reading this both angered me and left me with an unknown salty discharge. Thank you for sharing what has been a sobering read.

Salty discharge is part of the solution. And anger is an excellent fuel for action.

At once saddening and surprising because suicides among doctors in my India is nearly unheard of.

Actually more common in India than it may appear.

Do you know anything about the motives for the suicide of Dr. Dean Lorich? Thank you.

Nothing I can discuss publicly at this point. You can read the media. Lots of “theories” out there.

Dr. Wible: I am Dr. Dean Gerard Lorich’s wife. Nobody speaking out about my husband and the father of our three beautiful daughters has tried to contact me since his death.

Alternatively, how might I find you?

Deborah

I’m so glad you reached out. I didn’t know how to reach you and will email you right now. You can always contact me here and I will get back pretty quickly: https://www.idealmedicalcare.org/contact/

Your husband was much beloved by this group of orthopaedic surgeons and they really wanted to dedicate my keynote to him.

Ms Lorich:

I was one of Dean’s first residents at Jacobi, on the very first day that he began… I was a senior resident at the time. I had occasionally contacted him over the years with clinical questions as well. My deepest condolences on his passing. The entire orthopaedic community is diminished by his absence.

Jim McL.

Dear Dr. Wible:

Your presentation at the 19th Chicago Orthopedic Trauma Symposium was excellent. This is a follow up to the last audience response question after your talk. There is a body of literature that implicates the drugs used to treat mental health disorders may be causing more harm than appreciated. Since you are on the forefront of the suicide epidemic perhaps you will find this information relevant. The book

“Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America” (2010, Broadway Paperbacks)as well as Mad In America shed more light on this crisis.

Dear Paul,

This week on Mad in America, Martin Plöderl and Michael Hengartner discuss their recent research investigating the association between drug prescriptions for mood disorders and the suicide attempt rate among adolescents. Noting that their findings are in line with those from randomized controlled trials, they write: “Put together, these data strongly suggest that antidepressants can cause suicides and aggressive behavior,” despite mainstream psychiatry’s continued claims that these drugs reduce suicide risk.

Also in blogs this week, Helen Spandler reflects on what she has learned from working alongside psychiatric survivors for 30 years, writing that it has been “profoundly unsettling and challenging, but ultimately rewarding.” Patrick Landman examines “the psychoanalytic struggle against the DSM” over the past 40 years, and Eric Coates shares memories of a friend who had taken her life, writing that “the things that conspire to drive a person over the edge are too numerous and varied ever to point and say, it was this one.” And in this week’s personal story, Michelle Llamas shares her struggles with severe panic attacks and how a book she had dismissed as “self-help quackery” later showed her alternative methods of treating her problems.

In research news, we report on a new Journal of Mental Health article questioning the ethics and effectiveness of mental health services. We also take a look at the connection between education level and prescription drug misuse in young adults, how publication biases inflate the perceived efficacy of depression treatments, how peer support reduces chances of psychiatric readmission, and how prenatal exposure to SSRIs alters fetal neurodevelopment. And on our podcast, we speak with Sami Timimi, Peter Gordon and Stevie Lewis about their formal request to remove a UK Royal College of Psychiatrists representative from Public Health England’s review of prescribed drug dependence, due to his financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

As always, we welcome you to follow and join in on these critical conversations, and many others, through our news features and blogs.

Until next week,

Emmeline Mead, Managing Editor

Great article Pamela, I’m always scared when I see your posts because they’re so heartwrenching. But I think two things wee need to address. And they should start in medical school. Counseling students on how achieve work-life balance and how to maintain their relationships and marriages.

No other professions demands time away from family as much as doctors. Hospitals needs to ensure, they’re staffed well enough so that doctors are working shifts like everyone else and no not just simply filing forms about hours. They need to be grounded with their families. I think marriage breakdowns are a major source of pain and strife.

Absolutely. Given that some surgery programs used to BRAG about 100% divorce rates among their residents, I think this is a great idea! BTW, med students CHOSE those programs bc they thought they’d get better training there!!!!

My father was a physician. He did not directly commit suicide although I expected it. He did stop taking BP lowering meds… which probably contributed to an earlier onset of dementia… which did become a major factor in his death. One of his brothers did “actively” commit suicide. My sister is a practicing Midwife… and shared on FB your report with a comment that she identifies with one of the examples… I also would have to honestly “keep my hand raised”…

I’m grateful someone is even thinking about this…I just completed an orientation at a large, prestigious hospital and there was no mention of physician burn out or depression/suicide, just the usual about caring for the patient first etc. I’m concerned about the workload on the floors, there’s a maximum number of patients a nurse can have for safety reasons, yet no max for physicians…same old same old… Thanks for caring.

Michael Brown was a nutcase. Why include him with the others? I’m from Houston and his mental/drug issues were well known. It would have been there no matter what his profession was. Putting him alongside respectable doctors is a disgrace.

I realize the extent of his situation and untreated severe mental health condition. My registry reflects ALL doctor suicides—including homicide/suicides and others. As with all people and professions there are some who are more disturbed than others.

I mentioned to my psychiatrist who was treating me for depression and P.T.S.D. (who was also vetted to me as THE psychiatrist in my state to be seen by for physicians) that I was not suicidal any longer but that I was surprised that after three prior years of nearly daily SI that I had not acted on it. Within 24 hrs this psychiatrist without further evaluation recommended to the board that I no longer be allowed to see patients and I was ordered to cease practice. No transition period for my patients nor any possibility to find appropriate care for their follow up. I was told to give them a list of possible providers and that I was not allowed to explain to them any circumstances simply that I could no longer see them. I remain horrified and hesitant to consider returning to practice despite horrendous need in an underserved area.

Dr Ortiz was a wonderful surgeon and well liked in the community. Heard him speak at hospital marketing dinner lecture several years before his demise. Such a loss–unfortunate outcome for a wonderful surgeon.

Interesting, but being a surgeon myself I talk about there being one more layer of the cause.i.e. Stress and depression are reactive, not causative in these situations. Having worked in 4 countries(so far) there are national, cultural differences but the end-results rare the same. It is too easy to put it down to gender/race based discrimination or even perfectionism. Being surgeons describes us completely, as surgery is our vocation, our true calling. For starters, I would suggest dropping the P from PTSD. Interested in exploring this further? So far, I have been turned away from all doors I’ve knocked on, just to get those who should take notice to listen

Thank You for sharing this. I got chills reading the article. It further reinforces the fact that violence, suicide & mental illness are related and in many cases preventable, if we were to examine root causes,and explore systems-wide/community-wide strategies.

I am curious…did any of the ‘near miss’ doctors mention a history of Childhood Sexual Abuse or any other ACEs?

If you’re looking for excellent resources on prevention, see The Prevention Institute & Berkley Media Studies. BMSG just released a Guide on Sexual Abuse Prevention… I have found that the suggested strategies are relevant across health issues.

Thank you again for bringing this to light.

All the Best.

This is a very good research blog. I want to tell you how much I appreciated your clearly written and thought-provoking article.

I’ve followed you throughout the years and like how your presentations have become more data-driven (or “evidence-based”). Of course, I wish you didn’t have any data to work with, but I digress.

As a general pediatrician with a history of major depression, ADHD, and anxiety, here are 3 things that thus far, seem to work for me:

1) I DISCLOSE my diagnosis to my patients, within context, of course. By “patients”, I mean parents.

2) I ask MY patients to support ME. Sometimes, we need to forget the B.S. that patients cannot be our friends.

3) I try to have a hobby and share it with others as much as I can.

#3 is obvious. Talk to me about something I like and it’s like a mini-vacation. In the future, I’ll work on some sort of calendar so patients know there’s an event related to my hobby. There was an article in The New Yorker (I forgot now) that argued the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but human connection.

I disclose my diagnosis freely and gladly, again within the context of the encounter. Before, I was terrified of doing so (and still am, but do it anyway). The usual stresses of daily practice – finishing notes, patient care, going beyond to have a patient receive the care they need – can drive sane people crazy. We’re gonna fail because we’re not perfect. We do NOT understand that. But patients and parents DO. Especially when discussing mental health in children, the stress of parenthood, and usual “adult problems”.

The “cheerful doctor” acts this way because he/she needs to. Alcohol and drugs are a lot easier but much less creative. A teenager once asked, point-blank, if I ever thought about killing myself. I said: “No! I love food way too much!!” Which was my actual response to a previous program director who only viewed depression as a one-way street: unless I was suicidal, I should not bother anyone. It was a sign of weakness. Now, I ask for a hug after almost every encounter and I tend to receive at least 1, usually from the parent! This started one day simply because I truly needed a hug. I was giving some personal advice to the mom (well-known to me) of a beautiful, perfect baby. She lost her 1st child in devastating fashion from a heart defect. She needed a hug too, and from that day on, my personal RVU formula includes earning a hug from at least 75% of my patients. Most days, it’s usually 60%, but the ones I don’t get now, I’ll get later.

Don’t smoke, barely drink, and am scared to death of benzos. I use them sparingly (once a week) and only by the insistence of my psychiatrist. Though I’ve always been friendly, asking for help, much less affection, is something foreign.

My wife is amazing. She trained as a healthcare professional and currently stays at home with the children (a full-time job of its own). However, she still doesn’t understand why my depression and ADHD have not been “fixed” with medications, or why some nights I simply can’t sleep well. She does help me greatly, but we’re wired differently. My pre-teenage child knows I have depression, but we’ve never formally talked about it. Perhaps it’s time we did. It’s the bad thing about reaching out for help – if I fall, they’ll view it as their fault. A burden most of us do not want to pass on to our family. Which is the reason I tell my patients… so that burden is now shared.

You want me to write a letter to your insurance, another to your child’s school, and one to your employer, while working on prior authorizations? No problem – but I demand a hug or some outward form of encouragement to keep me going! It doesn’t have to be physical, but my empathy is not unlimited and as a salaried physician, get paid the same for every patient. These interactions almost always happen in the hallway, partly to avoid any “appearance” problems, partly to teach parents and patients “this is the way medicine is suppossed to be practiced”.

Also, thank you for mentioning that physicians can and do have children with health problems. One of my children is autistic… while the child has made FANTASTIC progress over the past 3 years, the thought that my child will not have a “regular” adulthood is a source of constant anguish. As I tell my patients: my child simply needs more help… but then again, which child doesn’t?

Ironically, I do NOT disclose my depression, ADHD, or anxiety to my physician colleagues. Hospitals may be callous, and health insurance companies are greedy, but it’s my physician collegues that will chit-chat among themselves, or send “anonymous concerns” to a superior. Our “public persona” may be “tell someone if you’re depressed, get help!” but physicians will be the first ones to not trust each other and refer to a committee or a medical board. Perhaps I’m a loner, but that’s been my experience.

The way I see it – I can certainly lend a hand to any of my personal physician friends. We do need to heal ourselves, but if patients want an empathetic physician that’s always available, they need to keep me healthy too.

“I DISCLOSE my diagnosis to my patients. I do NOT disclose my depression, ADHD, or anxiety to my physician colleagues.”

That really says it all. We have been pitted against one another and infighting among victims only perpetuates the stigma and isolation. We are brothers and sisters in medicine. We should be each others’ biggest cheerleaders.

I’ve followed you throughout the years and like how your presentations have become more data-driven (or “evidence-based”). Of course, I wish you didn’t have any data to work with, but I digress.

As a general pediatrician with a history of major depression, ADHD, and anxiety, here are 3 things that thus far, seem to work for me:

1) I DISCLOSE my diagnosis to my patients, within context, of course. By “patients”, I mean parents.

2) I ask MY patients to support ME. Sometimes, we need to forget the B.S. that patients cannot be our friends.

3) I try to have a hobby and share it with others as much as I can.

#3 is obvious. Talk to me about something I like and it’s like a mini-vacation. In the future, I’ll work on some sort of calendar so patients know there’s an event related to my hobby. There was an article in The New Yorker (I forgot now) that argued the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but human connection.

I disclose my diagnosis freely and gladly, again within the context of the encounter. Before, I was terrified of doing so (and still am, but do it anyway). The usual stresses of daily practice – finishing notes, patient care, going beyond to have a patient receive the care they need – can drive sane people crazy. We’re gonna fail because we’re not perfect. We do NOT understand that. But patients and parents DO. Especially when discussing mental health in children, the stress of parenthood, and usual “adult problems”.

The “cheerful doctor” acts this way because he/she needs to. Alcohol and drugs are a lot easier but much less creative. A teenager once asked, point-blank, if I ever thought about killing myself. I said: “No! I love food way too much!!” Which was my actual response to a previous program director who only viewed depression as a one-way street: unless I was suicidal, I should not bother anyone. It was a sign of weakness. Now, I ask for a hug after almost every encounter and I tend to receive at least 1, usually from the parent! This started one day simply because I truly needed a hug. I was giving some personal advice to the mom (well-known to me) of a beautiful, perfect baby. She lost her 1st child in devastating fashion from a heart defect. She needed a hug too, and from that day on, my personal RVU formula includes earning a hug from at least 75% of my patients. Most days, it’s usually 60%, but the ones I don’t get now, I’ll get later.

Don’t smoke, barely drink, and am scared to death of benzos. I use them sparingly (once a week) and only by the insistence of my psychiatrist. Though I’ve always been friendly, asking for help, much less affection, is something foreign.

My wife is amazing. She trained as a healthcare professional and currently stays at home with the children (a full-time job of its own). However, she still doesn’t understand why my depression and ADHD have not been “fixed” with medications, or why some nights I simply can’t sleep well. She does help me greatly, but we’re wired differently. My pre-teenage child knows I have depression, but we’ve never formally talked about it. Perhaps it’s time we did. It’s the bad thing about reaching out for help – if I fall, they’ll view it as their fault. A burden most of us do not want to pass on to our family. Which is the reason I tell my patients… so that burden is now shared.