Inspiring presentation to students at The University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine that received a standing ovation. Listen in below to full three-hour event (including Q/A) and/or transcribed presentation below:

Each year our future physicians enter medical school with their mental health on par with or better than their peers. The best and brightest humanitarians with a deep desire to help and heal others soon find themselves in a career with the highest suicide rate of any profession. How did medicine lose its way? How can we inspire students amid a culture that undermines their own mental health? Breaking through a century of medicine’s mental health stigma, Dr. Wible demonstrates how to be true to your original calling, and why being congruent with your deepest spiritual values turns medicine from a job into the most fulfilling career on the planet. (Plus loving your life as a doctor just might be the antidote to our physician suicide crisis)

Mark Clark, PhD: With physicians stories certain things kind of stick out to me. Particularly on the lookout for things that I think are possibilities of looking beyond somebody as simply a role model and a mentor. First thing that struck me early on in Dr. Wible’s biography was the fact that she’s a family physician and she started out around the time I was starting to get into medical humanity so early 2000, somewhere in there. She got frustrated in the struggle with all the weight of family practice—the direction her profession was going. So what she did was go off into the community, lead a town hall meeting and she asked what kind of clinic they wanted. And from there she got started developing a solo community clinic.

This is not exactly the subject of her talk today, but I thought it was important because what I see happening is this finding yourself in the condition of helplessness or vulnerability—but responding to that in action. So she had the town hall and she got going. When we talk about “burnout” we feel a true lack of agency. So what I want you guys to look at in mentors, in role models, in physicians is where especially they find a way to act—despite whatever circumstances they’re in—there is this agency and this capacity to act. That can really make a difference.

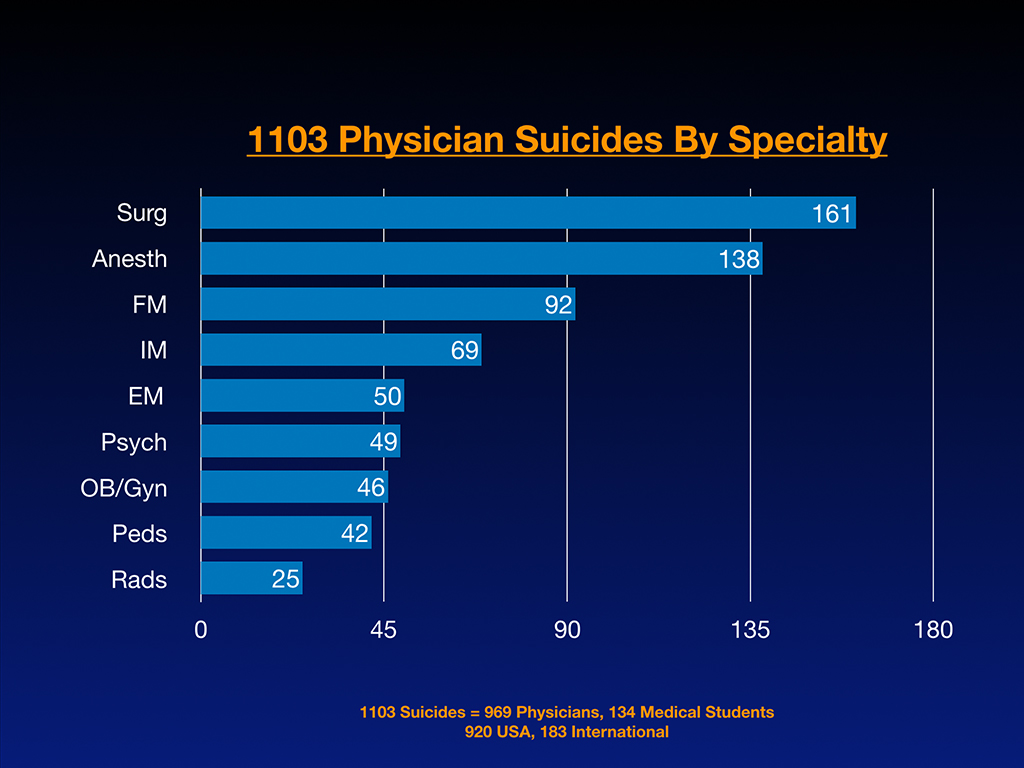

So she may talk about that. It really struck me as part of who she is and something that was worth noting. So she’s very active still in her family medicine clinic. Because of her own life experience, she’s gotten involved with physician suicide prevention. She’s investigated more than 1,100 doctor suicides and her extensive database and suicide registry reveals high-risk specialties—and solutions. In between treating her own patients Dr. Wible runs a free suicide hotline and has helped countless medical students and physicians heal from anxiety, depression, PTSD and suicidal thoughts so they can enjoy practicing medicine again.

I had several delightful conversations with Dr. Wible leading up to this event and I just felt like we are on the same wavelength. I was just incredibly happy when she presented me with the title of her talk which I thought was completely in line with what we have going on in unit nine and all the way through these last two years. Healing our healers—living your spiritual calling in medicine. Welcome Dr. Wible.

Pamela Wible, MD: Thank you so much for having me. I’m very, very excited to be here. Thank you for getting up early for me. So yeah, did you know that I almost went to med school in San Antonio? I only interviewed at two places. Back in the day when you could get into residency with only two residency applications. I got my top choice of residency and med school—and I only applied seriously to two med schools as well. But there was a cool thing with Texas, I don’t know if they still do it, where you apply with one application that goes to all schools. That was awesome. So yeah, I ended up at Galveston.

In my San Antonio interview, this old-guard med school guy was like really scary. He tried to scare us or something and I just thought, “Oh I love San Antonio but that was scary.” I’ve got to go somewhere where it’s safe. So I went to Galveston and I had my own issues there. But I’m glad that I went to UTMB, and my mom went to UTMB as well. So we just went back a few years ago to her 50th medical school reunion and it was my 22nd and there’s not many mother—daughter pairs that can go back to their medical school reunions together so that was pretty cool. Plants the seed for you all. Have your children come here I guess 25 years from now—and you can enjoy reunion together too!

So I thought we would do this in a really interactive and fun way where we could all learn together. Hopefully you all have index cards because I have a little experience for you all. I’m going to ask three questions. So on your index cards if you could just put one, two, three, one on top of the other. First question (don’t think too hard, just sort of stream of consciousness) is how old were you when you very first had the idea that you were born to be a healer or a doctor on this planet? The very first time you thought this could be your destiny. If you are on faculty, please answer these questions as well. You might want to make a note on your card that you are faculty. I would love to collect these at the end and just sort of see what everyone has written down. It would help me understand where medical students are today versus my experience 25 years ago.

So that’s the first question. Number two—what was your primary motivation back at that age when you first had that idea? What was your primary motivation in one or two words? Why is it that you wanted to pursue this profession?

And then number three. Same age. Take yourself back to that moment. What was your big dream that you had? Your original dream when you were four or five, eight years old—that original dream that you had to cure cancer, you wanted to be an amazing pediatric oncologist. Whatever it was that you thought that you were going to be at that moment. Maybe just a pediatrician in a small town or a family doctor. Write that down as well.

To find out the truth of what doctors are thinking, here’s my little Facebook question that I put out. Doctors—how old were you when you knew you were born to be a doctor/healer?

And boy, was this a really interesting adventure. I’m going to share some of the responses. First, I’m really curious in this room right now how many of you knew that you wanted to be a doctor, let’s say, in middle school? You knew by the time you were in middle school, like, what is that, 12 years old? By the time you were 12, just keep your hand up, by the time you were 12, you knew you wanted to be a doctor? Keep your hand up if you knew that you wanted to be a doctor by the time you were eight, you knew you wanted to be a doctor. How about by the time you were five? Keep your hand up. When you were four? Some people, how old were you? Yeah, when you knew you wanted to do this.

Medical Student: I was playing doctor when I was like four or five years old.

Pamela Wible, MD: So, four or five. Okay, what about our special dude in the back? Okay, so how old were you?

Medical Student: Four.

Pamela Wible, MD: Four, okay. So nobody was younger than four. In this room it starts at around four. It’s pretty cool when people get attached to their lifelong dream and I think that has a lot of relevance to how you proceed down your professional path. I’m going to share Facebook responses from some of my favorite physicians. Ann Cordum is an incredible internal medicine physician in her own practice in Boise, Idaho. And she’s one of those weird kids who at age five got her vaccines and was so excited, she knew right at the moment, like while all the other kids were crying, she thought it was the coolest thing ever and she knew she wanted to be a doctor. Isn’t that awesome? So cool.

And then we have Diane Pittman, an amazing woman, family physician who has her own ideal practice designed by her community in Minnesota. She bikes to work and does house calls. She’s super cool. Well turns out at four, she got bit by fire ants. Ended up with like anaphylactic reaction and getting rushed to a husband and wife physician team at their house and got the epi shot. That was her first experience of coming in contact with a female doctor. Since that age of four she was determined to be a female doctor and did not let anyone stop her. Apparently they kept giving her nurse kits and she’d trade them in for doctor kits.

Alright, then we have, this always amazes me. Joe Gates knew at age two. She’s a pediatrician. She knew when she was two years old that she would become a doctor. Often what happens, as you’ll see in her case is there’s a family member who was ill—her dad had back surgery. Well she was just so into it. Loved being in hospital, loved seeing how his care team was handling his case and just a super inquisitive child. Now she’s a pediatrician.

And then we have Madeleine—an internist in Pennsylvania. Interesting to me that she has nobody in her family in medicine. But somehow got so enthralled with her family medical encyclopedia that she kept running around, reading it over and over again, behind the couch, just hiding around with this encyclopedia and was determined to be a doctor from before elementary school. I just think this is amazing that people can hold on to their dreams that long. And they don’t obviously know what they’re getting into. She just loved her family medical encyclopedia.

My great friend Bob Calhoun just opened his own practice in Monroe, Louisiana. He knew at age eight. And his response here is pretty interesting. I’ll just read it.

I had played with the idea for longer than that but I made the decision that this is what I wanted to do with my life and had reasons for it at age eight. I had been interested in roles where I would be able to protect and help others for much longer, as far back as I can remember. I realized that I could help the most as a doctor at eight. I have always considered my profession as a divinely appointed calling, no less serious than the clergy which I’ve also considered at some point. And that’s how I have treated my job.

He’s an awesome guy, I love this guy.

So my question for you is do you feel that medicine is a divine calling for you? And I’m just curious with a show of hands, whether you were 22 years old when you felt called or four years old. How many of you feel some sort of divine calling? [most hands up in room]. Awesome. So keep that alive. That is very relevant. Many people make the decision to go into medicine as a second career and it’s made with less of a mind of a four year old and more of a logical linear decision making pattern. And so I just think this plays out in interesting ways in your career and you should be cognizant of the earliest motivations you have and the age that you decided to pursue medicine.

So I have this physician predestiny theory. This is just something that I made up. I make up a lot of things that make sense to me that guide me through life. May not make sense to others. But I will share with you my controversial answer to this question, which is that I believe we choose our parents before we’re born. And I know that’s very controversial but that’s what makes sense to me based on reflection of my life. And of course to be a healer, I chose two wounded healers as parents. That makes sense to me.

And so I can ultimately do what I’m doing now which is understand physician psychology at such a depth that I feel completely comfortable running a physician suicide helpline—with no training at all other than just the experience of being raised by two wounded physicians and seeing medical students wounded pretty terribly during my medical training and having a problem with that and feeling like something wasn’t right and then seeing the outcome of these wounds, 20, 30 years later in the way doctors behave and practice medicine. So I do think there is long-term mental health sequelae from what happens to us in training. So it’s very important that we’re trained in a humane and loving environment. As it appears your school is one of the more progressive in that area. So kudos to your dean Robyn and you all for creating such an ideal medical school environment.

So you don’t have to agree with me on this, but it seems to make sense to me. And when I posted this online, I wasn’t sure what the response would be. But what do you know. Sam Madeira, a naturopath on the East coast, feels exactly the same way. Phil Totonelly—a cardiologist outside of New York City felt the same way from early childhood. He felt like it was never really a choice—just a fact of life. He just felt drawn to this profession. And then a psych resident friend of mine writes, “If your theory is right then I definitely knew before I was born, because why else would you choose a life full of trauma unless you knew you were meant to be a psychiatrist.”

This is me and my dad. My dad’s a pathologist. And so in utero, I’m following my mom working in the emergency room as a resident. I was inundated with medicine from prebirth. I want to share my experience growing up with my dad, because I think it’s pretty unique in that, I’m just giving you a little timeline what it was like 50 years ago in medicine. Okay, so my dad, back in the day, you could actually bring your kids to work. So I would go work with him in the morgue as a child. And he would actually introduce me to his patients. He’d open up the big cooler doors and say, “Good morning, is anyone home?” He’d make it like a fun kids’ game. I didn’t have a babysitter ’cause I was a really difficult child (early challenges with authority) so my babysitters would always quit mid-shift, couldn’t handle me. So I’d always call my dad and say, “Another one just left. I’m home alone again.” So he’d have to take me to work.

So anyway, I just very comfortable just hanging out with my dad in the morgue—coolest place ever. Nobody ever disturbed us there. It was like our private little clubhouse. It’s not like my brothers and sisters wanted to be there. Nobody wants to go to the morgue. Except for me and my dad. Most people think about childhood memories of parents at their ballet recitals or around the Christmas tree or whatever. All I think about is me and my dad in the morgue. I know it sounds really strange.

I’ll share a little bit about physician psychology because I think some of you might have this distorted thinking pattern too—like my dad and my mom, but especially my dad was always afraid that he wouldn’t have enough money to retire. That he’d really have to scrounge around. It’s so weird because doctors feel like they’re going to be successful as a doctor or homeless. Such weird catastrophic thinking. Either I’m going to make it or I’m going to be a bag lady on the street. There’s nothing in between. But it’s weird. It’s like wait, you’re super intelligent and top one percent. Like there’s a lot of other things between homeless and doctor. But people just don’t process it that way. Very weird.

As a result of his fear of never having enough money or big enough pension, he ended up working all these truly “odd jobs.” In medicine, what is an odd job? Let’s see. Before 1985, it was uncommon for police to have breathalyzers so they used to have a doctor on site in the jail to process drunk drivers. So that was my dad’s job and I went with him every eighth night we slept in the jail together in our own little cinder block room with his doctor name on the door. With mostly African-American men in inner city Philadelphia. Such super funny fly guys. I loved it. I thought they were like a total crack up. I was just sitting there on the edge of this cot listening to them try to explain why they got brought in and when they started drinking mostly Thunderbird. I just thought this was fascinating.

He was on call for the Philadelphia Fire Department too. So we would have to go to major apartment fires and planes on fire at the airport. All sorts of weird stuff like that. And I just thought it was normal to sit in the lead fire truck while big buildings and warehouses are on fire. I never really understood what my dad was doing, just mostly drinking hot chocolate with the chief fire department guy, so it all seemed fun.

At the police department they kept trying to give me policeman coloring books each week. But I got so tired of coloring in the guy on horseback. And they only gave you four crayons. It wasn’t really meant for a whole evening of coloring. Policeman coloring books were to just entertain kids whose parents were in trouble with the law. But I was there every eighth day and night so I was tired of the coloring book routine. So I asked if I could interview the inmates—and they let me! I had to stay on female side—and they warned me not to get too close to the bars because they might grab me. But I literally started interviewing patients like on my own because I was getting sort of bored. And so I would ask them, “What brings you in?” I mean I was just kind of repeating what I would listen to my dad say.

So I started my own interviewing skills early on with dead people in the morgue, people who were caught for drunk driving. And Dad also worked at a methadone clinic in Camden, New Jersey. So he would sit me between him and his patients and he would introduce me as a doctor in training. This is what he’s say every time, “This is Pamela. She’s a doctor in training. Show her your track marks.” This is it, this is what I was doing, examining adults, their extremities, and listening to their whole situation with drug use.

As a result, I’m pretty fearless about death and mental health issues because my parents introduced me to the real world of poverty, racism, alcohol problems, drugs. I got introduced to that really early on. And the other thing that’s super cool that I have to share about my dad. My mom’s really cool too. She worked at a state hospital. But she didn’t have as many odd jobs as my dad. I don’t think she was as afraid of being homeless as my dad.

So anyway, this is super cool, like this so relevant I have to share. When my mom went into labor with me and went to the hospital, C-section actually, my dad was teaching at a med school called The Medical College of Pennsylvania which is I think it might be the first all-female medical school in the country. Just closed in 2001. But he was teaching there in 1967 when I was born. And so he actually polled the class to vote on what to name me. Isn’t that cool? And they voted Pamela. I was totally named by a medical school class. Is that like cool? And my mom wanted to name me Victoria. I don’t really like that name for me. Doesn’t really thrill me. Pamela means “sweet as honey.” Way better for me. Anyway, so according to my mom while she was like sedated, he snuck in and filled out the birth certificate. Constant battles between the two of them. They didn’t stay married for long, they got married on April Fools day.

Okay so my dream, I just wanted to share the background of what brought my dream to life. I wanted to be like my mom and dad and be there for people at their most vulnerable moment and help them through it—just talking to them. That’s what I thought was so cool about my parents. They didn’t look like they were doing a lot except drinking hot chocolate in the fire station and talking to really interesting guys that were drunk. But they were there at this moment in time that was really significant for the patient. And through talking to them, they were able to somehow inspire them and change their life and change their destiny. I just thought that was super cool. I wanted to do that too. Plus I’m sort of a voyeur now. I think some people go into medicine are just a little voyeuristic. It’s very interesting to hear about other people’s lives and then also help them. Not just pure voyeurism.

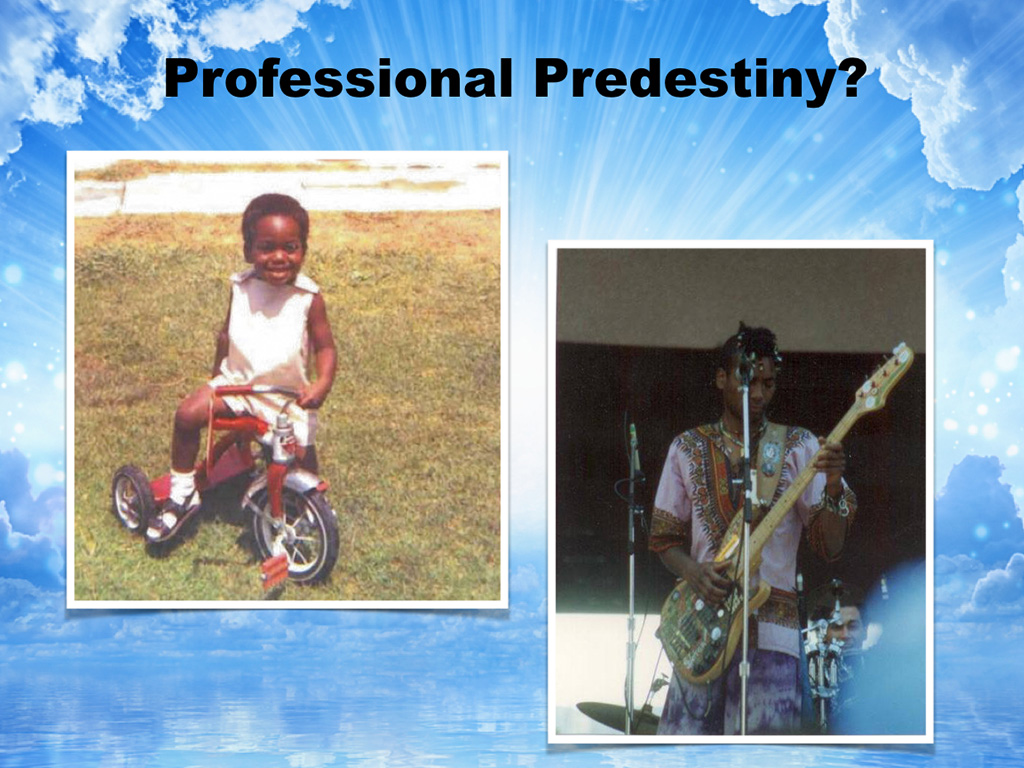

So professional predestiny does not just exist for physicians. I think that there are many other people in the world who know early on in life what it is that they want to do—like pilots. So I was interviewing pilots recently to find out, hey what age were you when you decided to become a pilot? That wasn’t really my original question for pilots. I was actually interviewing them about, not sure you’re familiar with this, but a few years ago there was a case with a medical emergency on a plane and a black female OB/GYN chief resident tried to assist and they told her to sit down and they were looking for a doctor. That was like some serious racism in the sky.

So anyway, I got interested in the whole triaging of medical emergencies on airplanes. And so I would spend a lot of my time on layovers sitting where all the pilots sit and flight attendants and just interviewing them. I asked them, “What’s your protocol if somebody loses consciousness on the plane? Who decides if there are five people running forward to help? Who are you going to pick? Are you going to pick the one that looks like Marcus Welby? Will you pick the one in flip-flops who is the chief resident? Or the one in sweat pants?” Like how are you going to make this decision because they don’t really know. And obviously flight attendants don’t have a lot of education in triaging medical emergencies for sure.

What I found really interesting from the pilots through all of this, I landed on the topic of how someone knows they will be a pilot. One pilot said, “Well you can always tell when you’re co-pilot is somebody who decided to become a pilot when they were a little kid.” The kids that have like the toy airplanes in their whole room, and they’ve been dreaming of flying since they came out of the womb. Obviously there are people who become pilots as a second career or even in the military or whatever. They’re approaching it very linearly without much excitement, just a job and let’s make sure everyone’s safe. But the ones that decided when they were five years old to be pilots, like every single time the plane takes off, they’re like, “Weeeeeee!.” They still have that childhood five-year-old bliss and excitement even though they’ve been flying planes for 30 years.

I want to introduce you to somebody else—my computer tech. He’s such a sweetheart. This is him when he was little. And he definitely had some professional predestiny because when his parents got out this record player (he loved music, but he never knew where the music was coming from until his dad put a record player down on the floor). Well when he saw it spinning around, he was completely enthralled. He put up his hand to stop anyone from getting near him or interrupting him. He would not come to dinner. He would not come to meals. He would talk to people. All he wanted to do was look at the record player and change the records. His dad taught him how to do this and now as a result of this absolute complete fascination with music and machinery, he’s a computer tech and a musician and that’s something again that started around age two for him. They used to call him the naked house DJ. He’d never wear clothes and just sit by the record player.

So I just want to take you back to that original dream that you had and to think about what your primary motivation was at that age. Here’s a list of primary motivations. Why don’t you look at what you wrote for question number two and compare it with this list and see if what you wrote down is on this list. So there’s healing and helping others; academic stimulation and science; money and security (and none of these are the wrong answer). Some of you are like the first person in your family to go college or to medical school. It’s a very honorable thing to do to have a secure profession and be able to care for your parents later in life and that sort of thing. So if money and security is your motivator that’s also fine. Prestige and status. Some people are doing this primarily to make their parents happy. That can backfire if that’s your only reason. And relationships with patients. And then some of you are adrenaline junkies, let’s just face it—you’re going to be perfect for emergency. Trauma surgeons.

So I’m just curious, how many people in here are in it primarily for, like choose one of these if you can. Who in here does not see their motivator on this list? What is your motivator?

Medical Student: So my primary thing is to make change, changes, to change the system, to change the world we live in.

Pamela Wible, MD: Okay, cool. Awesome. So I guess the rest of you fit on the list here somewhere. How many of you are adrenaline junkies? One, two, three. Okay. Alright. How many of you are in it primarily, number one for relationships with patients? Three or so, okay. How about to make your parents happy? One. Okay. And what about prestige and status as a primary motivator? Nobody. What about money and security as a primary motivator? One. Okay, nothing wrong with that. And what about academic stimulation? Alright, we’ve got about 10 or so. And what about healing and helping other. Aha, the majority. Okay, that’s where I thought it would be. Just curious.

The third question is—what is your original dream? And I’d be really curious for a few of you to share what your original dream was. My original dream, which I didn’t really share yet is that I wanted to be a family doctor and I wanted to do the whole womb-to-tomb thing and see everyone. I kept having recurrent dreams of finding people stranded on beaches and highways and bandaging them up and bringing them to my house and giving them tea and sitting with them and watching them in a rocking chair and then releasing them at some point. Like, I guess, holding them hostage until they healed and then letting them go and finding more random people on the street. That was just a thing that I had. I don’t know. It’s weird. Anyone else want to share your original dream?

Medical Student: So I have no idea why, but my mom said before I was even school age I used to say all the time that I wanted to be a brain surgeon. We don’t have any doctors in our family. I don’t know where I got it from, but that was like my thing was that I wanted to be a brain surgeon and not a heart surgeon, because if you mess up on someone’s heart they would die. That’s what I would tell my mom.

Pamela Wible, MD: So do you still want to be a brain surgeon?

Medical Student: No.

Pamela Wible, MD: What about you?

Medical Student: I think when I discovered I wanted to be a physician I used to always say I wanted to be a pediatrician, and then as I got older I realized I love kids but not that much.

Pamela Wible, MD: I’m with you on that.

Medical Student: So it started out as a pediatrician, and then I kind of developed the mindset, like you said, I wanted to follow my patients from the womb-to-tomb kind of thing.

Pamela Wible, MD: Awesome. Anyone else want to share?

Medical Student: I know I wanted to be a pediatrician as well, ’cause that was the first doctor I saw, and when I went to the doctor I always had a great time, but I don’t like kids that much. I switched it later on. I like kids, but I like to give them away to their own parents, so I think I’m interested in OB/GYN.

Pamela Wible, MD: All right, awesome. So I want you all to really hold that original dream in your mind as you’re going through medical school. Whether you end up bringing it to fruition or not, it is relevant. The important thing is to let your original dream guide you, not be fixed to it, not to be rigidly attached to it but let it guide you. And this beautiful image here that I was inspired to share is just kind of a picture of professional predestiny. There’s the excitement for what you’re going to do in your life, and I think sometimes it’s with us from the very beginning, from age two, from when we first see a medical encyclopedia, from when we first see a record player, you know.

The important thing to do is be flexible, because the danger is I’m going to share with you some things that I wish people would’ve shared with me as a second-year medical student before going on to my clinical rotations, but if you become too rigid and fixed to your dream then you could actually sort of have a psychological meltdown and feel a complete sense of despair if for some reason something happens that does not allow you at least in that moment you don’t think that it is any longer possible to have that original dream.

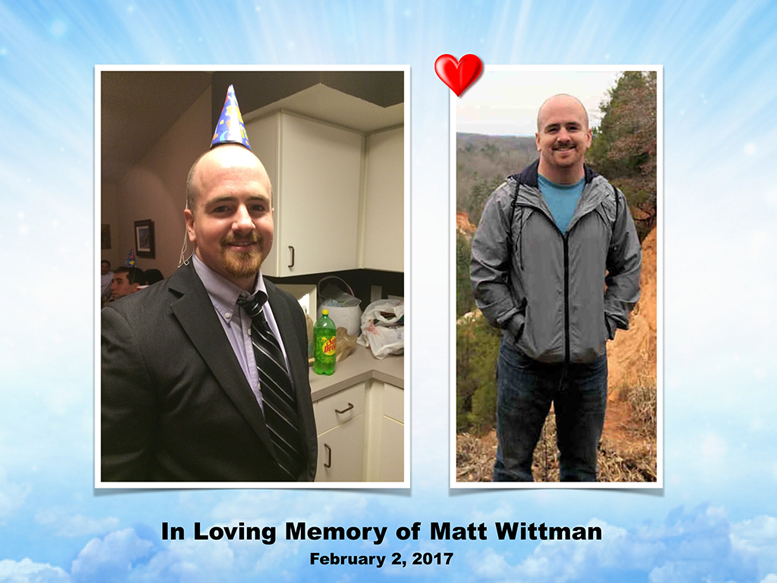

To drive the point home, I want to introduce you to Matt Witman, a second-year medical student who died by suicide because he lost his dream in his second year of medical school.

I’m going to share how that happened. These are his parents, and this is his college graduation from Florida State University. I have a letter from Matt’s parents that I brought that they wanted me to share with you, and this will help you understand what was going through a second-year medical student’s mind that led to this catastrophic decision.

Dear Medical Student,

I can’t imagine the stress and anxiety that you feel right now. However, I can certainly understand how you may feel given the demands of medical school. We lost our son Matt, a second-year medical student, to suicide in February of 2017. He left this world in complete despair, hopelessness, and in his mind nowhere to turn for help. Unfortunately for all of us, he didn’t share these feelings with anybody, not his classmates, his church friends, or his parents. Only after we met the dean of the medical college after his death did we realize he had failed his second class and was in jeopardy of not being allowed to take Step 1 of the USMLE in the coming months. Also, we found out in his short time at medical school that he had amassed $100,000 in student loan debt. All of these factors certainly weighed heavily on him.

About our son: all he wanted to be in life was a physician. From about the age of 13, that is all he wanted. He had a less-than-stellar MCAT, and he tried for three years to get into medical school. He was finally accepted due to his practical experience as a crisis line counselor and EMT. Unfortunately, he refused to even talk about a Plan B, and as he was applying for a second and third time to medical school. He refused to discuss a Plan B after he started school and was not doing well.

In the summer before his death, he announced he wasn’t going to call us on Sunday, as was the practice in our family. In fact, he told us he might call us only once in a few months. Those months went by with one call from him, then the dreaded call in February informing us of his suicide. Matt did not discuss his challenges and his apparent increasing depression with anybody. When we met his classmates at the memorial, they looked to us for information as to how and why this could happen. None of them had any idea. Same when we met with his church group and the folks he spent time with on the weekends. None of them had any idea either that Matt was struggling and in such despair.

So why am I telling you this story of our son? I want you to know there are people who love you, people who want to hear from you, especially in tough times. I want to make sure you understand that we are here for you. We may not know you, but we are here for you. We have so wished our son had confided in us regarding his struggles, if not just to give us the chance to give him some kind words and hope for his future. We were not so fortunate.

There are many resources for you if you are feeling the stress and anxiety that our son did. We would recommend, as we told my son’s classmates at his memorial, that you please call your parents, call your siblings, reconnect with them if you have been too busy to do so in the past. Share your thoughts with them. Talk to your classmates. You may be surprised to find some of them experiencing the same challenges. If you are active in a church, mosque, or synagogue, talk to your pastor or church elder. You may be surprised that you are not the first student with your challenges. Seek out medical help. Our son was clearly depressed, but he kept it from everyone. He couldn’t overcome the stigma of a medical professional seeking mental health counseling. That stigma is over. I know deans of medical colleges that are actively trying to get the word out to their students to not be afraid to seek counseling, as nobody should bear the burdens of medical school by themselves. You are not alone.

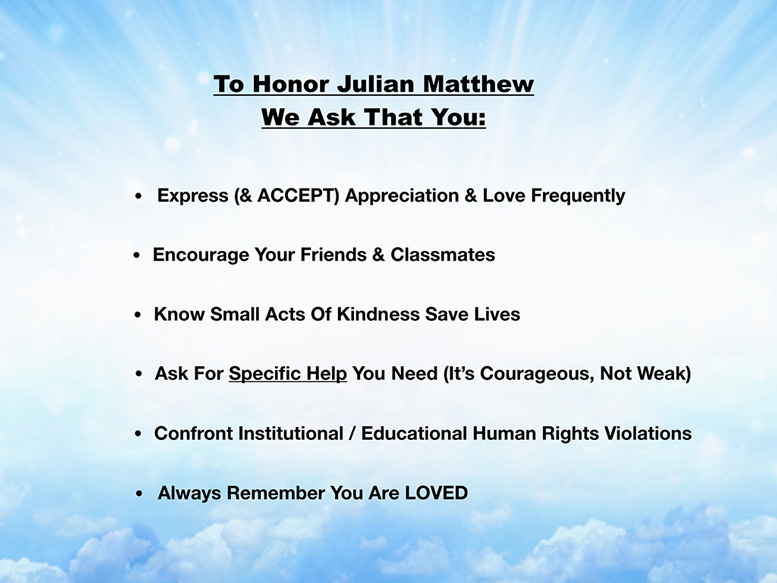

~ Julie and Clay Whitman

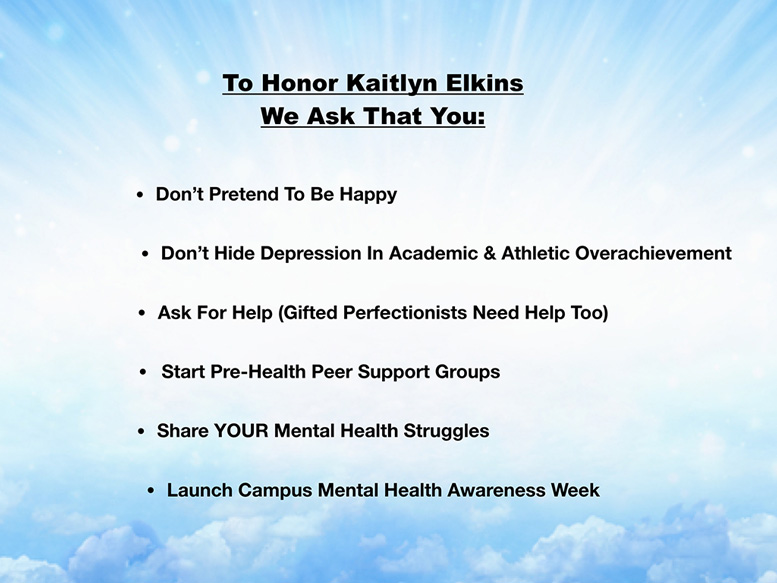

So, to honor Matt Whitman, Julie and Clay and I, your faculty and your dean are asking that you please always have a Plan B, because successful people know when to quit. That’s really important. Don’t isolate from friends and family and classmates. Please share your feelings with someone. I know men in this society are indoctrinated pretty heavily not to cry and be the tough guy and be the fix-it man, but I think that can really backfire in the field of medicine. If you contain all the suffering and pain that you have and all your patients tell you . . . well, you just you cannot contain all that as a lifestyle. So I think it’s really important during medical school when you’re learning how to do blood pressures, how to do exams, how to, you know, you’re probably practicing on each other at times different techniques and different exams, ear, nose, throat, you can practice sharing your feelings with each other, too. There is no shame in sharing how you are feeling and doing mental health check-ins with one another as part of your routine. You don’t have to just answer you’re doing fine and everything’s great if you’re feeling sad.

In Matt’s situation, he died in his apartment. He slit his femoral artery. Parents were at his apartment when an Amazon box came the next day. Inside they found a bottle of St. John’s Wort, so obviously Matt knew he was depressed because he had ordered St. John’s Wort (an herbal medication for depression). So we also ask that you please seek mental health care as soon as possible you feel depressed. Don’t just try to order stuff on Amazon and figure it all out yourself. Not a good idea. Realize that your life is more important than any career and that you are loved, and there is so much awaiting you in your future, and it’s not a catastrophe if you have to reroute your career. It might mean there’s something better for you, okay? So please be open-minded about that.

So here’s me and my mom and dad at my graduation from college when I was super excited, can’t wait to get to medical school. Do you see that face? I am just invincible, unstoppable, so excited, and here are a few pictures from my childhood so you can see I’m the type of person that’s bursting with joy, can’t wait to get going, super-optimistic, idealistic type of person. But I want you to just at look at my eyes and look at how I am in these photos as I share an interesting situation that my mom put me through as a child.

So, when I was little she was in her psychiatry residency, and obviously she was studying all the time. Her idea of a bedtime story for me was to read her psychiatry journals to me and then stop on every pharmaceutical ad and make me stare at the picture of the freaked-out human being’s face and tell her a story about what’s going on with the person in picture. So I got really good at looking at people’s faces and figuring out what is really going on and seeing through the fake smile and all the stuff people try to do and get away with. I got pretty keen early on. These are mostly 1970s ads for Valium, so lots of housewives running around with their Valium to survive having children and cleaning the house and all that stuff.

Anyway, so this is how I looked before medical school, and here’s how I looked at graduation. That’s not the same excited, exuberant face. That looks like, to me, that I’m supposed to smile for that photo because it’s graduation day. It looks like I survived a war or something. It just looks terrible. And I did. There’s a picture of me in medical school laying on the floor collapsed with the guy on the floor with me is a man that I dated in medical school for three years, and he died by suicide, actually. Not while I was dating him. I want to make sure everyone understands that.

Both men that I dated in medical school died by suicide. I dated my anatomy partner, and he died by suicide when he was 39, married with two children, and then this gentleman that I dated for three years.

Which, by the way, this is, of course, before Instagram and cell phones. This is the only picture I have of him. I dated him for three years. This is the only picture I have of us together during medical school. I think that’s kind of weird. I think it definitely drives home the point a picture’s worth a thousand words, right? This is very significant that that’s why I’m not really smiling so much at graduation.

I was really traumatized via medical training, especially in my first year of medical school. It got better as I went, but mostly traumatized because of the dog labs they forced us to do, which was just horrendous. We had to murder people’s prior pets. They thought this was a great physiology lab experience, which is why I didn’t go to San Antonio for medical school because the guy, during our interview process, made a joke about how we’re all going to murder dogs, and I was like, “I got to get out of here.” I almost was going to faint. I was so sick. I couldn’t take the barbaric behavior. Okay, so, thank God medical schools don’t do this anymore.

My life totally sucked during my first year of medical school, and I cried most of the time. One morning I had cried so much that my eyes were sealed shut, and I couldn’t even go to class. I was really depressed. And I tried to get help from my parents, but my parents are not super emotionally and spiritually checked-in people. My dad’s more like an absent-minded-professor-type guy, and my mom is more like a drill sergeant, so you can’t get a lot of help. My mom basically sent me Trazodone in the mail. She mailed me psych drugs in the mail, and she didn’t really want to hear anything about how I was feeling exactly. My dad was pretty much like, “It’ll get better. Everyone goes through this. Just focus on this future,” or whatever. So it was like I did not feel like even my parents could be helpful, and they knew what I was going through because didn’t they go through medical school when it was even worse, like in the 1960s and the 1950s? Even worse.

But anyway, my life totally sucked. It did get better in medical school. I loved my family medicine residency. Awesome.

So my dream that I had of being this womb-to-tomb doctor doing house calls, being in a small town … Actually, my original dream was to be on the border of Texas and Mexico and have a family practice office and do house calls and do all this stuff. Then I ended up in Oregon. This is about being flexible. You might not end up in the city that you think you’re going to. What kept me alive, literally, during my most depressed moments was that I still had that dream. My dream is what propelled me forward, ’cause I knew it’ll get better if I just make it through. My dream can come to life, and it’ll be smooth sailing afterwards.

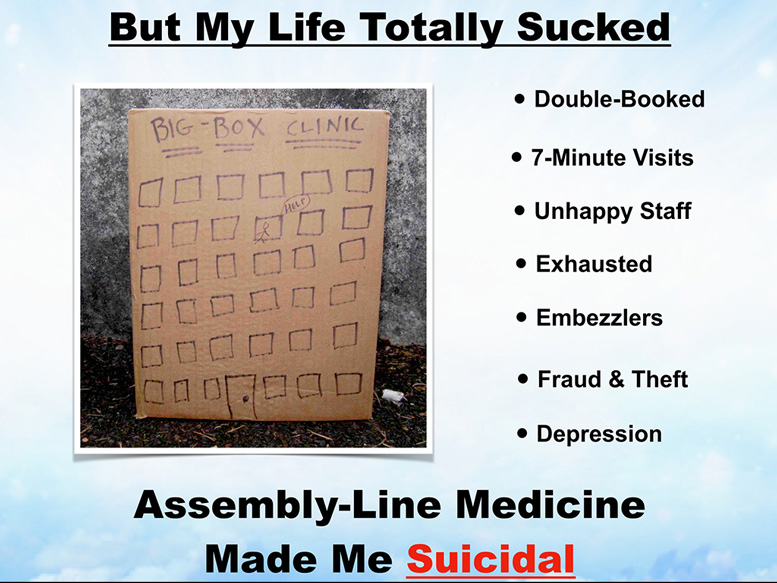

Joke was on me because my life totally sucked after residency because I ended up in what I call a big-box clinic. This is my little art project to try to rehab from the pain of being trapped in a big-box clinic. I don’t know if you’ve been at a big-box clinic as a patient or shadowing, but this is what it was like for me. It was like double-booked. I didn’t even know what double-booked means. That means two people shoved into a 15-minute appointment, they give you two people in the slot, so now you have two 7-minute appointments. How do you actually see somebody in seven minutes? Sometimes you’re triple-booked, so that’s a 5-minute appointment. Staff is unhappy ’cause how could you be happy if the patients aren’t getting the care they need and they’re yelling at you, and how do you even put people through a system in 7 minutes? It’s impossible.

And then I was exhausted ’cause I was seeing over 30 patients a day, and then we found out our clinic manager was embezzling money from the clinic. If you’re seeing patients every seven minutes, guess what? That’s an open door for embezzlers to come in, and when you’re trying to do your job all these other people are trying to run off with the money you’re generating. That’s just what happens at these clinics. There’s a lot of fraud and theft, insurance fraud for sure. People are upcoding, lying on the medical record.

I saw all this stuff at these different clinics, and so it made me depressed. I said, “Oh my gosh, I went through like 24 years of school, kindergarten through the end of my residency non-stop, and this is what I’m in,” and I felt like I was trapped in assembly-line medicine. Don’t worry, there’s a happily-ever-after ending for me and everyone else. But it made me suicidal. The fact that I had a dream that was completely thwarted by the healthcare system.

I just want to drive home the point this is my perspective. I think many people agree. Assembly-line medicine is dangerous. It’s dangerous for the patient because they’re not getting the care they need. It’s unsustainable for the physician, emotionally, physically, spiritually, and financially.

These large systems just don’t make any sense. For example, if you have an ingrown toenail, you shouldn’t have to go to a five-story hospital with a helipad and a five-story parking garage and wait in a cafeteria-style waiting room when you could walk down the street in your own neighborhood to a doctor who can see you. I’m in a 280-square-foot office, so I have low overhead, low volume. Major problem, by the way, what really fractures everyone’s dreams in medicine, is that you get forced by economic pressure of these unsustainable large systems. Essentially, primary care is held hostage to a tertiary care delivery model, if that makes sense to you. You’re subsidizing off the ingrown toenail the helipad, the electricity for the five-story hospital. A call to action: simplify your life and live your dream and let go of all the infrastructure you don’t need, because it will get in your way and suck down all your revenue.

And by the way, at my favorite factory job, my overhead was 74%, which meant that I brought in, back in 2001 or so, $500,000 a year to that clinic, yet the overhead was $370,000, which meant that my salary was like $110,000, plus I was supposed to get a $20,000 bonus, but I had to fight for two years to get it, because even doctors that I thought were my friends were willing to walk off with the money that I was promised.

So, anyway, 74% overhead means that when you see a patient and they give you, say, 100 bucks for the visit and you have 74% overhead, that means that you’re earning $26 pre-tax for that visit. Now my overhead is less than 10%, which means I get to keep 90, right? This is an example of the business of medicine and basic economics that if you can keep your overhead low, you can keep the money that you’re generating and pay off your student loans sooner.

Also if you open your own clinic and it’s a non-profit (yes! you can start your own non-profit clinic) you can get loan forgiveness of your student loans. That’s just a really big thing that … ’cause a lot of people end up working at FQHCs, Federally Qualified Health Centers, or working for somebody else that has a non-profit, but they don’t necessarily like the business model they are or it turns out to be an assembly-line type of non-profit scenario. So I just want you to know that’s an option. You can open your own non-profit clinic and get complete loan forgiveness, so that’s cool.

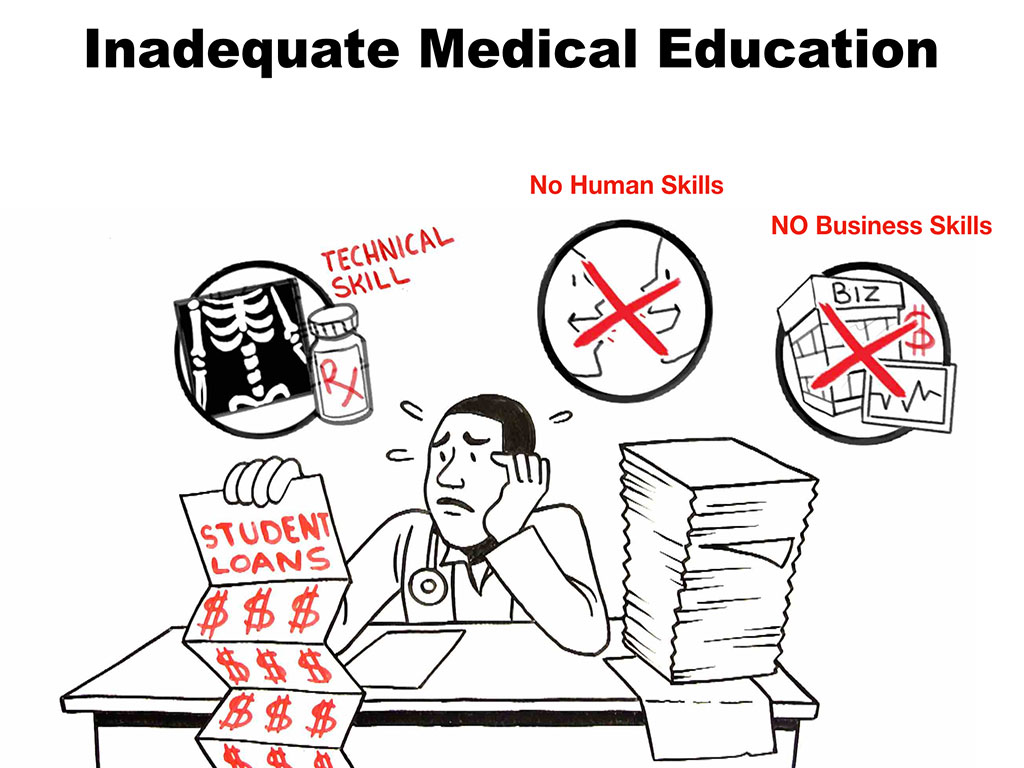

So how did this happen to us that we ended up stuck on these assembly lines? And this is my experience of medical education. Your medical school is so much better than what I went through, but this is my experience, and I think an experience that a lot of physicians can relate to, is that medical education was inadequate in two areas.

Of course med school gives you the technical skill that you needed so that you could be in the specialty of your choice. However, at least in my medical training, I didn’t get any human skills, and I definitely did not get any business skills, and I didn’t get business skills in residency, either. So you end up technically skilled to do something that’s a high-revenue-generating activity but no business sense to actually own what you earn, so you have a bunch of other “helpers” that come in—third parties that want to “help you” along and take a huge cut of your revenue.

Back to the 74% overhead, I want to just explain that would be equivalent of moving to a state that has 74% income tax. Who would do that? Would you move to a state that takes 74% of your income. That’s what you’re doing when you work at a big-box clinic. They take 74%. You are giving away so much of your blood, sweat and tears and intellect to somebody else who’s got a GED or an MBA or whoever these people are. Anyway, just letting you know.

So, the options that you have in training, what I feel like medical students and physicians are pushed into with your newfound technical skills—your choice is which assembly line do you want to sign up for? That’s pretty much the choice. Do you want to do treadmill OB? Or rat race pediatrics? Or drive-by psychiatry? Which you know doesn’t work. This is not going to work, this is not going to help the mental health of our country to get seven-minute quickie visits. I know a doctor in my town that does 6-10 psych patients per hour, and they’re very serious schizophrenic-type patients. And so you know people are not getting the care they need when they’re pushed through drive-by psychiatry clinics. So things just get worse and people wonder, “Why was there a school shooting?” and “Why did this tragedy happen?” Well, drive-by psychiatry with all the black box warnings on all the drugs and not monitoring these people properly and changing their meds could lead to unstable citizens. Assembly line urology is kind of weird too, and so I just want you to know that there’s a better way to do it and I’m going to share that today.

Medical education for me felt like an anti-mentorship program. I don’t think that’s your case here. You have a lot of wonderful faculty and people that are really inspiring that I’ve met, and so I’m just explaining what it’s like for me and what it’s like for many people today in not-so-progressive medical schools. A lot of this has to do with our mentors, the people who are training us, have been wounded by the old style of medical education. They’ve all had to kill dogs. They’ve all had to do things that were against their ethics during medical training, and so when they start bullying you and say, “You have it better than us,” and, “You’re a snowflake,” all those comments they make, that’s coming from people that have mental health wounds from their training, so have compassion for them. They’re hurting. I don’t know if you’ve heard the line, “Hurt people hurt people,” but that’s kind of a cycle that you get stuck in. So an antimentorship program just means you meet a lot of doctors you’d never want to become. It doesn’t look like their life is going well.. They had five divorces, they work 100 hours a week. That’s not what I want to sign up for, right?

And so we’ve lost our mentors. I think when you get right down to it, what is the main problem that is fueling the degradation of our profession is that we have lost our mentors—and this is an apprenticeship profession. When you don’t have mentors you end up sort of lost at sea and clinging to whatever piece of plywood floats by and then jumping on and hoping you can make a life for yourself. I mean, this is really dangerous when you don’t have mentors, and so I want to help you have mentors.

There’s a few secrets I want to share. Secret number one was to please hold on to your original dream but not too rigidly. Be flexible so that if something happens you don’t end up thinking, “I want to slice my femoral artery. I’m out of here.” Really, it’s not that bad. There’s a lot of cool things you can do with your life.

Secret two is I want you to find your mentors, and I’m going to give you some cool ideas on how you can do this. First of all, you should avoid cynics. If there are people that say, “Oh, you can’t start your own business in healthcare,” or, “You’re too idealistic” Has anyone ever heard, “You’re too idealistic”? Raise your hand if you’ve ever heard, “You’re too idealistic.” [Half the room raises hands] I heard that all the time. Terrible. That’s a terrible thing to say.

That might not be a good mentor, just FYI. “That will never work.” These are statements coming from people who’ve been injured, and I think it’s really important that you find somebody who is mentally well and really loves their job and can demonstrate what it’s like to be a really happy OB/GYN or emergency doctor or family medicine.

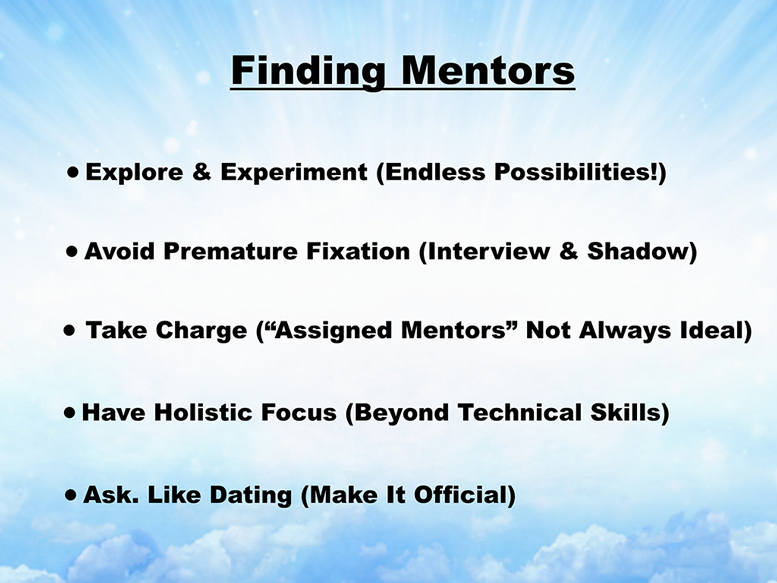

So finding mentors, here are some ideas. So, first of all, it’s really important not to prematurely focus on just one avenue for your future. Explore and meet as many people as possible, because there’s really endless opportunities for mentorship. You could be mentored even from somebody a year below you with physician parents. You could be mentored by your own physician that you happen to like or your own pediatrician, right? Just be open to who comes into your life. I’m happy to be your mentor. If you need a mentor, you can’t find anyone, and you think anything I said today made sense, you could contact me.

Also avoid premature fixation, which is what I’m trying to get you to do. Interview and shadow as many people as possible. And I want you to take charge. Sometimes people are assigned mentors. That’s like an arranged marriage. That could work for some people. Sometimes there’s no love there. So I want you to realize that assigned mentors are not always ideal, and so I want you to take charge and look around and find your own mentor.

Have a holistic focus. If there’s somebody that you think is an awesome brain surgeon but they’ve had like five marriages and they’re estranged from their children, they might not be the best all-around mentor because they’re off-kilter. You know what I mean? So think about … ‘Cause sometimes when we think about mentorship, we think about technical skill aquisition and who’s got that knowledge and who’s ahead of me on the path, but I think we need balance. We need to love the rest of our life. We need a real mentor that is person that you can look up to as a whole unit.

It’s amazing how physicians I’ve asked who are my age and 10 or 20 years above and below my age, “Have you had a mentor in medicine?” and they’ll say, “I’ve never had a mentor.” Isn’t that sad? To make it to 50 or 60 years old in medicine and you’ve never had a mentor? I don’t want you to be one of those people who says, “I never had a mentor,” That means that you might have had a lot of bumps in the road that were unnecessary that could’ve been prevented by kind of like setting your GPS properly and having somebody tell you, “This is the best way to go, and here’s the scenic route.” You want to get the secret recipe to how to become an OB/GYN the easier way or the better residency and that sort of thing.

So, I want you to take it really seriously, almost like you would dating or marriage. If you’re listening to advice from the wrong mentor, you could end up in the wrong specialty in the wrong city, and it’s not pretty. You’ve got to find people you that admire, and then ask them like dating, “Hey, would you be my mentor?’ and just realize that that is an honor for them. Some people think, “Well, I don’t want to put them out. They seem so busy,” but for you to ask somebody this is a huge honor, and it makes them feel appreciated and loved. And it’s really kind of a mutually-beneficial relationship because when you ask them questions it gets them thinking, and they feel like they’re sort of teaching again, and they get to look at their life anew, and so it’s a really beautiful relationship. So I would encourage you to have at least one mentor, maybe more, and then have a structure like you meet once a month or you have a phone call every week or something so that you have an ongoing … Don’t just leave it free-flow. Make it official.

Secret number three: this is the one that excites me more than anything. This is the one that if somebody would’ve clued me in in high school to this one, it could’ve saved me 20 years of agony, seriously, which is you need to know whether by nature you’re an employee, a business owner, or an entrepreneur.

I’m going to give you a little cheat sheet. And you should write this down as number four on your index card, because by the next few slides I want you to write down your answer. You might feel like you’re in between one or the other, but try to write down the one that you think you’re closest to, okay?

So how do you know what you are supposed to be when you grow up? Okay. Because the thing is if you just pick your career based on your technical interests or somebody who was nice to you on a rotation, sometimes people pick their specialty because, “I know in these three rotations, these guys were mean to me, but the woman doc on this rotation was nice to me, so maybe I’ll go into this specialty.”

Don’t pick a specialty based on who was nice to you. It’s a combination of multiple factors and one of which that should be weighing heavily is whether you’re an employee, a business owner or an entrepreneur. Because if you’re a neonatologist, you’re probably going to be an employee, right? If you are a family doctor, you could be an entrepreneur or a business owner.

Some people are choosing professions based on perceived lifestyle. I’m going to do radiology. Well you are going to be an employee and you’ve got some high capital expense and you may be in a straight jacket, and you better get along a lot of people and be a team player. Don’t have a lot of original ideas. Some specialties are not open to that.

So anyway, here’s how you figure it out. Employees generally are risk averse. Business owners are risk tolerant and entrepreneurs love risks. They’re the kind that jump out of planes and decide they’re going to start a whole new business that nobody’s heard of and they feel like it’s going to work. And nothing stops them. You know where I am. I’m in the entrepreneur category.

Employees love structure. Business owners enjoy structure because you need a little bit for a business to work. Entrepreneurs hate structure. They go on and do something different every day. Life is a supposed to be an adventure.

Employees follow rules. It feels safe when there’s rules, they feel safe knowing where the edge is, where their cubicle is. They want to know what they’re supposed to do. They want to read their job description, and they want to do it well.

Business owners respect rules and want to enforce them but they want to be in charge of the rule making. Very different situation there.

And entrepreneurs don’t really like rules. I’m making some generalizations here, but it’s like rules are too confining. That means I can’t have creative thoughts and do something completely different tomorrow.

Employees generally, there’s some motivated employees, but in general when you look at these three categories, employees have lower motivation. Business owners are very self motivated, and entrepreneurs have extreme motivation and sometimes rarely sleep. They’re so excited about whatever they’re going to do next.

And employees tend to be more self and family oriented. Thank God it’s Friday, barbecues on Saturday. I’m going to see my neice on Sunday, I’m going to go to church. They like the structure of here’s what I’m doing every week and watch the clock, five o’clock time to go, see ya on Monday. That’s an employee, right?

Business owner is community oriented. I want to start this business and really serve my community. I’m thinking beyond just seeing my niece and my mom and going to a barbecue. I’m thinking of how can I improve my community. Entrepreneurs want to change the whole world overnight with some cool idea they think of in a dream.

Employees really like stable income. Business owners are profit-driven. They have to be to succeed in their business. Entrepreneurs are not really profit-driven as much as passion-driven. They don’t care as much about how much money they have at the end of the day, but they want to know that what they did improved the world and they had a message and they got it out there.

Employees really like routine. They feel safe when there’s a routine. Business owners like control, and entrepreneurs don’t like routine, because the root of the word routine comes from rut. Who wants to be in a rut? I mean this is me talking, right? So I’m not really into routine. I get bored easily, especially if I have to do the same thing two days in a row. Okay. So there we go.

I’m just going to leave this up for a minute and have you look at that list and think about where do you feel like your basic nature lies? Do you feel like you’re really at your core an employee? Do you feel like you’re more of an entrepreneur, or do you feel like a business owner? Just write that town. And some of you might feel like I’m part business owner, part entrepreneur. I’m a halfway employee and part business owner. But if you had to pick one, just write that down on number four. And I’m very curious, how many of you feel like your employees? Okay, so maybe is that 25% of the room or a third? Okay. How many of you feel like you’re business owners? Many more business owners. Okay. How many of you feel like you’re entrepreneurs? Okay. Not quite as many as the employees.

So I have this feeling that most physicians are really by nature, at least business owners. Okay? And many are entrepreneurs. And if you put a business owner or an entrepreneur in an employee position, that’s going suck, whether it’s a 30-minute visit, a 60-minute visit, a seven-minute visit. This was key for me to understand, and I only, by the way, I understood this when I turned 45. I’m trying to help you understand something. Oh my gosh, my life would have been so different if I understood that I was an entrepreneur.

So anyway, I launched my own clinic twice, which was awesome. After my first job, which was an assembly-line clinic in Eugene, Oregon, I was completely frustrated with how they were doing things. And so I just thought I could do things better. So I opened a clinic in a converted carport at my house for all uninsured, and I did that at age 29, and I just traded, I don’t know, carrot juice and whatever people wanted to pay. And it was 14 to one hundred dollars sliding scale and you got a discount if you rode your bike or took the bus. And I had a gift basket. It was really fun, but the thing is … And I actually did make $30,000 that first year, which is pretty good. A lot of doctors when first launching clinics (usaully high-overhead assembly-line clinics) don’t make any money because their overhead’s so high. It takes them a while. So I made more in my cheapo little clinic in my house than many doctors their first year.

But anyway, so that was my first attempt, which I really loved, except that since I’m an entrepreneur, but I didn’t know at the time, I think I had some restlessness because I need to change the world. I have this change-the-world, change-the-world spirit. And how am I going to change the world if I’m in a carport in my house where it’s a cool happily-ever-after kinda thing in Eugene, Oregon, but this isn’t going to change medicine. Most doctors aren’t going to quit their jobs and open in carport clinic for poor people and giving carrot juice and trading for tofu. Most docs are not going to do that.

And so I just felt this urge to jump back in with my newfound knowledge, jump back into medicine in an employee situation because I didn’t know I was a business owner or an entrepreneur. I still didn’t get it back then, but I jumped back in so I could almost spy and see what’s really going on and try to figure more out because I knew there was something else that I was supposed to do but I didn’t know what it was.

So I jumped back in, and isn’t it cool? I jumped back in and landed in a clinic with your med school dean Robyn as my colleague. We worked in the same clinic 20 years ago! Isn’t that amazing? I hadn’t seen her for 20 years. We were at Lake Forest Park Medical Clinic together as colleagues. And I knew what she looked like but I hardly spent at any time with her because this is one of those run-around-in-circles clinics, a small clinic with only five doctors. But I felt like I was confined to my one little corner. So I think I saw her at a distance, probably like we are here. And I said, “Hi Robyn. Good morning.” But we never really got to know each other—until two nights ago at dinner!

And she was just the same. She hasn’t aged a day in 20 years. Look how beautiful she is. Oh my gosh, she’s doing something right. You guys are keeping her young. She’s in her dream job in her ideal medical school. That’s why. So I went back into the beast, okay. And I took notes, and I felt like I was like a little bit of an investigative spy reporter thing, and I tried another few jobs and then finally I was like, this isn’t working. I got to do something different.

I moved back to Eugene. Basically after six jobs in ten years, I ended up feeling like, oh my gosh, this is as good as it’s going to get. They were all numbers game, production-line jobs, so I basically got super depressed and ended up in bed—suicidal for six weeks because I was like, oh my gosh, there’s no way to be a doctor in this country. I haven’t found my dream job, and I’m 36 years old and I’ve tried six jobs.

I was at my wits end, but I ended up figuring out that I could do things completely differently in a cool way that has now been replicated all across the country—and I’m going to share what I did, which is I became a real doctor in a community designed clinic. I’m going to share more about how I do this, but it’s super cool. Out of my depression and my suicidality, I had an epiphany through some sort of a weird prophetic dream/vision where I saw people coming together and designing our own clinics and hospitals and I was like, Whoa, that’s the solution! I just got to stop being an employee in these large systems and invite the patients to be in charge!

This is by the way, the most progressive way to do anything is you invite the end user to design their own system. So for example, I think the most progressive medical school would be designed by medical students, because they know what works for them, right? I think the most progressive medical clinic should be designed by the patients in the community that the clinic is going to serve. That way they feel like a sense of ownership with the clinic.

So I did a series of town hall meetings. I know it sounds really weird. I went from laying in bed for six weeks, hoping to die, praying to die, but as a vegetarian, healthy 36-year-old woman, it just didn’t happen, fortunately it didn’t happen. So I’m still here to talk about it. So I had that vision and I literally jumped out of bed and called the newspaper and let them know that I was going to lead a series of town hall meetings and invite the community of Lane County, Oregon to design their own medical clinic.

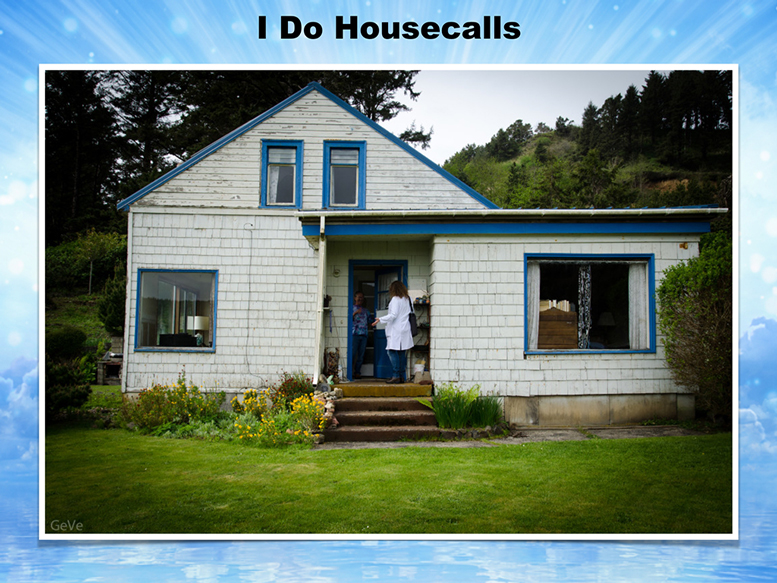

And that’s what I did. And these are just news clips from TV stations and Al Jazeera America and the Harvard Business Review. View TV and film clips here. What we did gained a lot of traction and ended up getting in the media because it’s so unique. What patient gets to design their own medical clinic. I had them basically write my job description for me. And so now I do house calls, which I never was able to do in those employed jobs. This is me seeing one of my favorite patients, Johnny, at his house.

Look at this, overlooking the Pacific Ocean on a hundred foot cliff and his yard, which he gets to stay there for free. He used to be the landscaper, and the woman won’t sell this property, and so she let him live there for the rest of his life for free, which is so sweet.

And so I go to visit him. He has terrible arthritis. He can’t really drive so far, it’s a hundred miles from my clinic. People come to see me from hundreds of miles away because they want a doctor who delivers relationship-driven care and gives them more than seven minutes, right?

And then I have time to do house calls for the homeless. Okay, because when you’re your own business owner and entrepreneur, you can basically say, “okay, I’m leaving at three to sit under the underpass, hang out with homeless, see what they need.” And you could just spontaneously do that. You don’t have to ask permission, you don’t have to get the day off.

I have done quadracycle visits. Okay, this is a patient of mine where I did a house call, and then he wanted to just do the visit on his bike, so we rode around town, and took the chart note sitting on my laptop there. Isn’t that cool? On his bike. He’s super cool. I love this guy.

And then I did a surprise birthday physical for my friend. You know how you remember some peoples’ birthdays and and then some people you go oh no, another year went by and I forgot, and I’ll give them a belated birthday call or whatever. So I’m like, “Ah, next year I’m gonna do this thing where I’m going to remind you and have a physical on your birthday, and then I’m gonna …” Basically I got all of her friends to hide in the bathroom. And so when she went around the corner to get undressed, everyone jumped out with balloons and that’s just one of the fun things you can do. Obviously I don’t do this for every visit. I’m just giving you a sense of you don’t have to be in seven-minute cubicle situation.

So you could be here in your ideal clinic, and this is what I’m hoping for you all, that you have your ideal life as a doctor in the right specialty for you with an awesome mentor and that you can create the business structure that’s going to work best for your personality, and you can be in the town that you love and deliver the care to the population that you feel called to serve. And so what I want to share with you that’s super cool is I actually brought the town hall testimony from my clinic, the hundred pages that I got from the keynote. I’m going to pass this around so you can look at it, but I’m going to read a few things that people actually said to me, and I’m going to share these with you.

So basically there was a sheet that I handed out so that the meetings were about an hour long. I did nine of them over six weeks. And it just says, “Create your ideal medical practice. Please take time to imagine what it would be like to walk into an ideal medical clinic and an optimal health care system. We will embark on a meditation during which time you may jot down your wildest dreams and most creative ideas. Afterwards, we will share our insights and consider implementation strategies.”

So it’s a blank sheet at the bottom. They can put their name and phone number if they want to be involved or if they want me to call them when when the clinic is open. So that’s what I did. I love this first one. It used to make me cry every time I read it, it’s just so poetic.

So I’m just gonna read a few excerpts of what patients really want from you. Okay? No matter what your specialty is, I think most people just want basics, right?

A sanctuary, a safe place, a place of wisdom where we can learn to live harmlessly, listen with empathy and observe without judgment. A place where a revolution starts. A new way of seeing where we rediscover our priorities. A place to learn to live, a place to learn to die.

A place where the doctor is happy.

The doctor is waiting for me when I arrive.

No high front counters and benches separating people from people. Maybe a lounge of sorts. Sofas, not hard chairs. No old magazines that make you think of your own mortality and how many years have passed. Interesting books on house, music that is comforting but not schmaltzy. Rooms set up in some rustic, homey theme. Already is too much stainless steel and gauze. Fun surgical gowns, complimentary massage while waiting.

I did that by the way. There’s basically massage therapists in every town who need to get hours of experience and you can bring them into your practice and they will massage your patients for free and get credit for their graduation. So that’s a way that you can do it. I was having people get foot and hand massages during their appointments where they’re sitting there, talking about their psych issues. They felt really happy. Okay. So let’s see. A few more . . .

Small living room style, welcoming room with cushions on the floor, comfortable chairs, relaxing music, herbal teas, a books with words of wisdom, meetings for food, drug and alcohol and cigarette addicts, Tarot card readings and spiritual cleansing ceremonies.

I obviously can’t do like everything but I can refer them to people who do the things that I don’t do. Let’s see. Barter for trade, barter produce, vegetables, plumbing, cleaning. I do all that. So I do most of the things they said.

Most important is to feel heard, understood and cared for no matter how long you need to babble to get your point across.

Minimum of 30-minute office visits.

Healing is not symptom suppression. Work with the body, not drug people beyond recognition. Abolish cookie cutter medicine. Everybody doesn’t need the same thing.

The doctor knows everyone by their first name. The doctor knows the patients in a social context, the doctor appreciates the link between mental health and physical health. So the doctor prescribes meditation, Yoga. The doctor knows something about nutrition, duh.

I would like to be treated as a peer and not a commodity. I want to sit in a comfortable room with overstuffed chairs. Eliminate the medical assistant who weighs and measures and takes notes that the physician doesn’t read anyway. Sufficient time to make this seem as though the visit is between peers.

Low overhead kept small and personal.

Is self employed or works in a small office, doctor owned.

I’d like to see a relatively relaxed physician in a calm space, someone who has plenty of time off.

That’s awesome. And I just have to read my favorite one. I love this guy. This was my first patient and by the way, he walked in for his first appointment with very high blood pressure. A skinny little macrobiotic guy that lives in the woods, uninsured, he ended up having renal artery stenosis and it was like my most amazing case of my career of catching something. And then making time and following him straight and convincing him to go to the hospital because the guy is so funny. He just kept me laughing the whole time because he anyway, didn’t want to go. But you’ll see. This is what he wrote on his little thing. He’s this guy with dreadlocks, skinny little hippie guy from the woods. Okay. What he wanted is . . .

They would have a pet cat that will greet you in the waiting room. Houseplants, cool kids’ toys, good and intriguing magazines that I will ask to borrow and I will have time to read. A clean space, friendly, relaxed workers that I know, a community of doctors that work in all types of practices and work together to heal the people in need. Massage, western and eastern medicine, acupuncture, and whatever else is available from this cohesive community of healers. [This next line is my favorite line ever from any of these] They have a big garden and a running stream. You come over for lunch and play with the pet goat who inadvertently heals your broken leg.

Every visit with him is like a complete crackup, but his blood pressure, well he’s getting ready to die, but I’m still laughing. And he’s asking, “Well, what if I stop eating peanut butter?” And his blood pressure’s 220 over, and I was like, “No, I think we really should go to the hospital.” He’s like, “Should I just not drink pickle juice? Would that help?” We’re sitting on the couch and I’m like, “What about if we call your parents and head to the hospital?” It took him a while, but he finally agreed, but I really had to seduce him into it. You know what I mean? So anyway, I just want you to know how cool it is to have your own clinic and have these amazing patients.

So secret number four is, it’s very important to connect spiritually with your patients. Now if you stay spiritually connected with your original dream and that beautiful natal picture, then you’re probably more likely to be able to spiritually connect with your patients, because you wont be disconnected yourself.

One of the things that’s a funny pet peeve of mine is all these doctors are going to integrative medicine practices. You’ve probably heard of that, right? But they’re not really integrated themselves. You know what I mean? They’re kind of a mess. Now they have a wellness center, and they’re offering integrative medicine when they’re not connected spiritually, emotionally they’re a mess, they probably have a little PTSD and their marriage is on the rocks. They’re not really too integrated themselves.

So I would suggest that you get integrated and stay connected with yourself, your dreams, your heart, your soul, because you’re going to be able to connect with your patients better.

These are three questions that I have on my intake form. What is your life purpose? What is your dream? What is your vision? I have all the other questions like cardiovascular disease in your family, diabetes. I have the regular intake form, but I add these questions at the end.With some patients that are really existential thinkers we spent the entire 60 minutes on what is your life purpose! It was a young guy in his twenties and he was just like, “Wow, nobody has asked me that.” And he’s like, “I’m going to have to think about this.” And we had to talk about it. He was really into it. He came back the second time to continue to talk about the life purpose question.

So anyway, I just think this helps you bond with your patients at such a deeper level. Even if you’re a trauma surgeon, even if you’re emergency doc. As long as they’re not coding, right? You can ask these questions. Very important to get to know who the person is that you’re treating because everyone is different and unique and deserves a unique way of dealing with them. They’ll be more compliant and agreeable with a treatment plan if it is in alignment and congruent with their spiritual values and their cultural values.

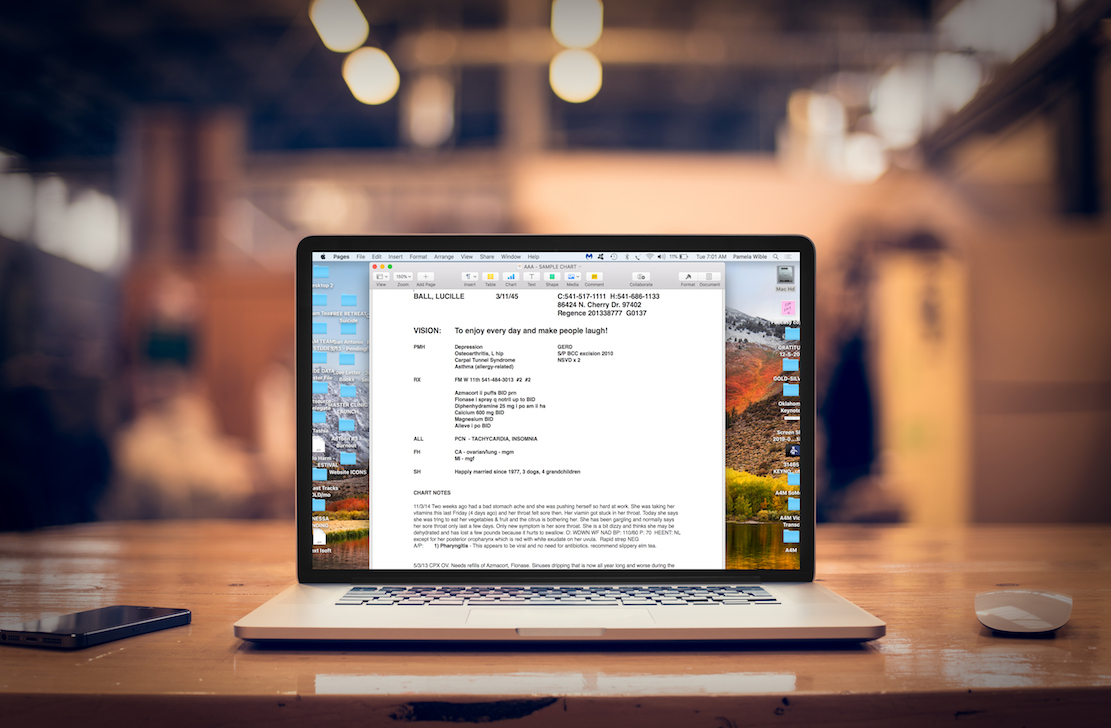

So this is actually, I wanted to show you a picture of my electronic medical record that I created on my own. I don’t even use a purchased system. I made my own electronic medical record with off-the-shelf software that came with my Apple laptop. This is a closer view. It’s a sample patient, Lucille Ball 🙂 and at the very top I have a vision. On every one of my patient’s charts, I start with their vision for their life ’cause I want to know if their vision is to be with their grandkids every day or their vision is to make other people laugh or whatever their thing is or to be of service to God. To open a chart and to first see that in bold just really sets the tone for the appointments so that we’re connected spiritually.

And I would encourage you, even if you’re on Epic medical records or one of those other systems to have some place in there where you can make a note, some spiritual information and their social history or just their life purpose somewhere. It will really help you bond with your patients and they’ll connect with you. And it’s just fun. You can be human together, not just like a factory worker.

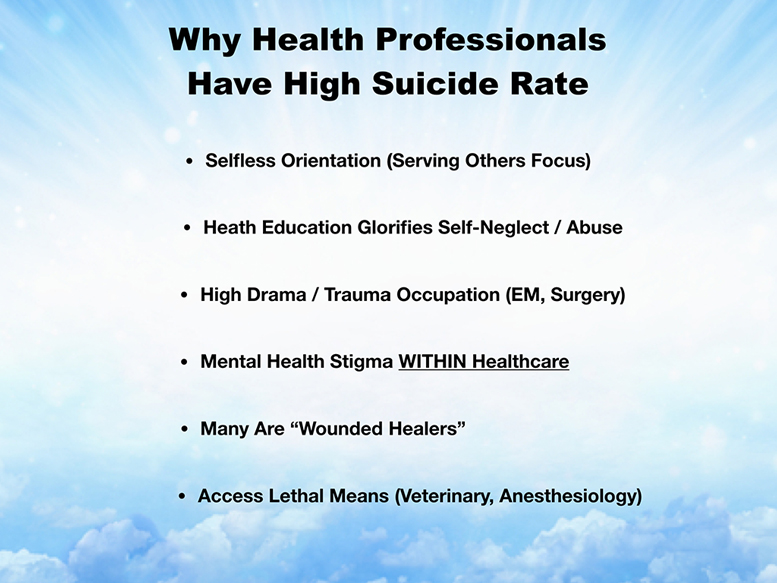

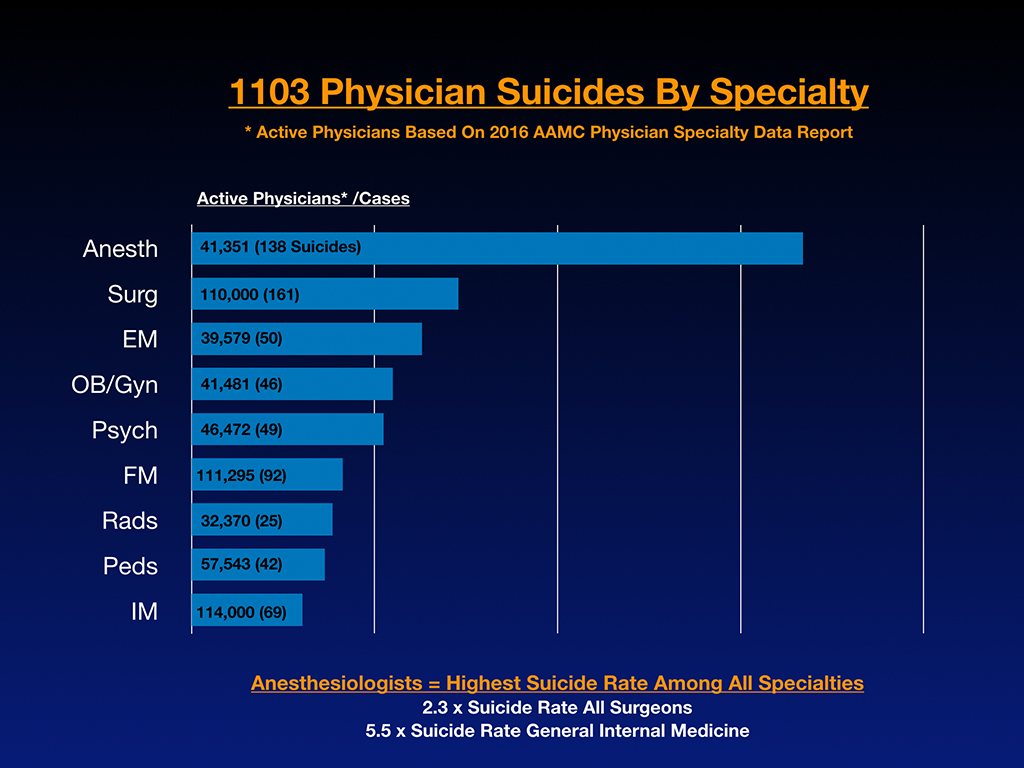

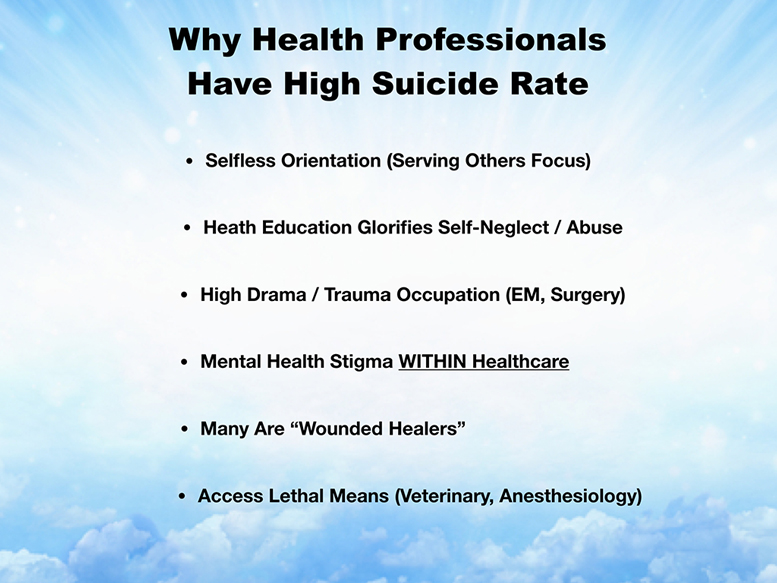

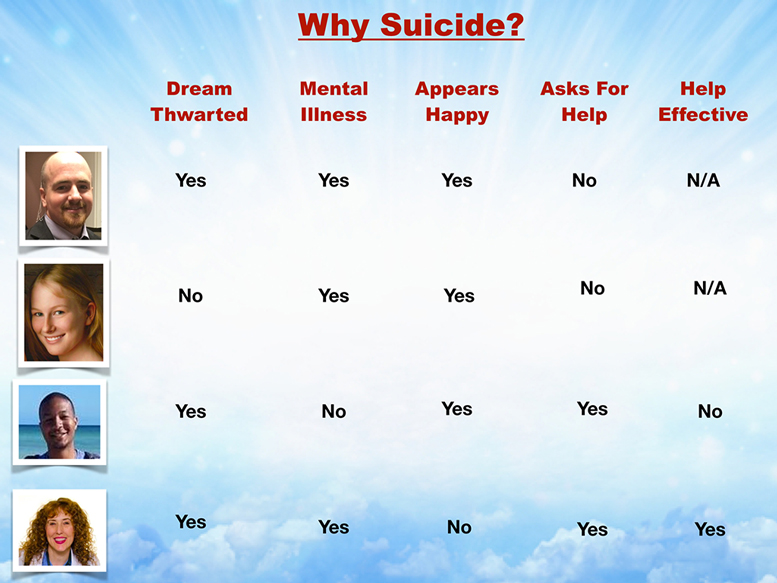

So secret number five is it’s very important to know the health professions mental health risks. There are significant differences and mental health risks between specialties. And what I feel that happens is people pick medical school and specialties without informed consent. And it really pisses me off because you end up in a the wrong career that can risk your life. Isn’t informed consent so important in medicine? If you get this procedure, you have a 10% risk of this, and it’s going to take you this many weeks to recover. And that’s just common sense. But people are ending up in medical school and hurry third year, fourth year, choose a specialty, hurry, you got a match, and they’re in their rush to suddenly pick something, and they’ve never received informed consent about what the mental health risks are. If you already have like a drug addiction issue from high school or a suicide attempt or something, maybe you don’t want to be a male anesthesiologist since they have the highest suicide rate of any combination of gender and specialty.

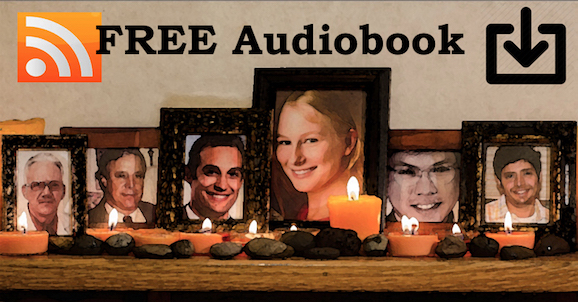

So these are things that I think people need to know ahead of time. Not once, they’ve already picked a specialty and they’re suffering. So I’m going to just share with you, this is a wall in my house with pictures of some of the now 1,208 doctor and medical student suicides that I’ve investigated.

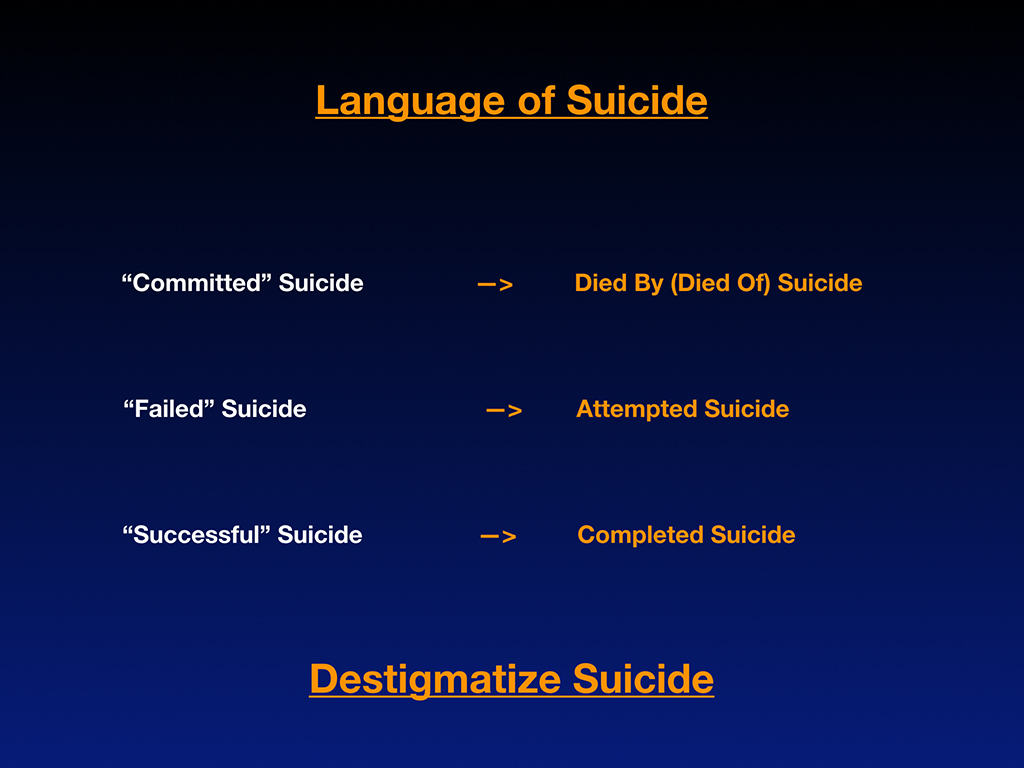

And so I have a very deep understanding of why people choose suicide in medicine and what specialties are more likely to succumb to these sorts of terrible decisions. And before we dive into it, I just want to share a little bit of the language of suicide because this is such a taboo topic. It’s very hard for people to discuss it without a huge emotional overlay. And I think if we could just use factual terminology, that would help. That does not stigmatize the conversation.

So it’s really not a good idea, even though everyone in newscasters still say “committed suicide” because “committed” makes it sound like a crime, like committed burglary, rape or something like that. These are people who are hopeless, who are in pain and they feel like their only way out is to stop breathing. So they’re not committing a crime. They have not found an answer for their pain in drive by psychiatry or whatever they sought. Just say “died by” or “died of suicide,” that will help kind of like died by pneumonia, heart attack, just to take the emotion out of it and just deal with the facts.

And they used to use this term, I don’t know if you still do or you’ve heard it, “failed suicide,” which is an attempted suicide that failed. Well how could that be a failure when you have a 20 year old who attempted suicide and he survived. That’s a success. They’re still here. So the whole idea that you failed your suicide attempt is ridiculous, and then a successful suicide. Matt had a successful suicide. How is that a success? He’s dead. That’s a completed suicide. That is a very sad situation for somebody who needed help and for whatever reason was not able to ask for it as a second-year medical student.