Residents in Salem, Oregon, are designing an ideal medical clinic. Slated to open by April 2013, the clinic may feature a dinosaur exam table, a cool gecko that greets patients at the front desk, and maybe even a pet goat. But the final design will be determined by citizens gathering at town hall meetings over the next few months.

Community-designed health care is nothing new. Citizens in Eugene, Oregon, pioneered the first community-designed ideal clinic back in 2005 (see video). Now, ideal clinics have opened all across America.

Dr. Lara Knudsen, a board-certified family physician, and her husband, Chris, are bringing ideal medical care to families in Salem at Happy Docs Neighbors’ Clinic. They imagine relaxed appointments; walking visits in a beautiful park; patients’ pictures on the walls; superhero gowns; weekend hours when the whole family comes in; an annual clinic picnic; and lots of laughter.

Now, Lara and Chris are turning their dream over to the community. They’re asking residents to design Salem’s ideal clinic. I spoke with them after their first town hall meeting to find out how things are going.

Pamela: “What are you specifically asking citizens to do?”

Lara: “We want to know what patients would love to get out of seeing their doctor, what they imagine an ideal clinic would look, smell, sound, and feel like. We are asking citizens to attend one of our town hall meetings and share in writing, voice, song, prose, or dance their wildest ideas.”

Pamela: “Why open an ideal clinic?”

Lara: “In medical school and residency, I often questioned my choice to go into medicine. Pretty early on I realized that when I had TIME with people, to sit on their hospital bed and hear about their families and jobs and lives, then there were few things I loved more than medicine. It’s hard to have enough time with patients when working in a large system, so I quit my job and decided to ask the community to help me design an ideal clinic.”

Chris: “The big secret is that most of the things that patients hate about the system are exactly the things that doctors hate. Most of the things that patients want are what doctors want, too. So why not put our heads together and figure out a way to make our clinic what WE—patients, families, and doctors—want? Let’s build a beautiful healthful system, however small, that we can all be proud of, that reflects our values and encourages us to treat one another as neighbors.”

Pamela: “How did your first town hall meeting go tonight?”

Lara: “We met for an hour and a half at the Salem library. We handed out paper, pens, markers, and asked folks to imagine their ideal clinic. People were already brainstorming about ways they could help. They didn’t share everything on their sheets so when we got home and read the comments, it was really like Christmas as a kid. I should be headed off to bed, but I am still tingly and excited from it.”

Pamela: “What makes a doctor all tingly and excited?”

Chris: “It’s connection with patients. Folks had so many cool things to say. One man, a current patient, told me after the town hall that he and his wife believe that Lara’s approach to caring for him saved his life. Now he wants to give back to Lara and the community. And another patient hadn’t gone to a doctor for 67 years. He was literally shaking when he met Lara. A shut-in, scared and diabetic, he came and shared his love for Lara and his aim to help us create a clinic. It was really wonderful.”

Pamela: “So now patients are healing doctors?”

Lara: “Yes. Healing goes both ways. The current system is dehumanizing for patients—and doctors.”

Chris: “Doctors who don’t know you flipping through charts asking you the same questions over and over again is depersonalizing for everyone. A guy offered this analogy: ‘It’s like when you go to your public defender and you’re in court and he tells you, ‘Just say no, no, no, to everything.’ And you’re like, ‘But what about my case? What about my file?’ And he’s like, ‘You think I have time to read that stuff? I don’t have time to read anything.’”

Pamela: “Yeah, great analogy. So who came up with the idea for a dinosaur exam table?”

Chris: “A 20-something computer store employee said, ‘If the exam bed were in the shape of a dinosaur, I would go to the doctor then!’ So now we’re looking for carpenters to make our dino-exam table.”

Pamela: “And someone else wanted geckos?”

Chris: “As brainstorm fodder, I wrote words and questions on the white board. One word was animals? So a guy asked, ‘What did you mean by animals?’ I told him some clinics have cats, dogs, fish, and even therapy goats. He smiled and looked relieved, ‘Well then I would say geckos. We have a gecko and he is really cool and I would love to bring him.’”

Pamela: “What surprised you most from the evening?”

Lara: “People thought that we’d get overwhelmed, inundated by patients. ‘Everyone in town will want you!’ one guy said. We told him that yes, at some point, we’d post a notice on the website: ‘Sorry, but we are not accepting new patients until our current ones get healthier. Keep checking back though!’ And one guy in the back (the same guy who talked about his public defender’s lack of personal attention) said, ‘You know? That makes me feel accountable to other patients. Like, knowing that other people won’t get to be in this clinic because I am still sick would actually motivate me to take better care of myself.’”

Chris: “Amazing! We hadn’t even thought about that, but it creates patient accountability. Patients will rise to the level of functionality we expect. And that guy blew us away with this immediate understanding of what we were getting at. He saw it before we did.”

Pamela: “So how can people get involved? What do you say to get folks to participate?”

Lara: “Attend the next town hall meeting! Would you and your in-laws like to have a dinner with me? Perhaps your church has members who would like to help design an ideal community clinic. What about your classroom of third graders? Your coworkers, softball team, economics class, motorcycle club? We want to build our meetings through the people we meet. More adventure that way. So send us your group, the number of people, and a proposed date and time. We’ll fit you in.”

Pamela: “Anything else?”

Chris: “Location! Think outside of the sterile, florescent-lit, paper-gowned box. Think of the coolest, most comfortable, most convenient place where you would want to visit your doctor. Then consider if you have friends who happen to have that place. Look for easy walking distance to a park, 250 square feet minimum, and rent between free or barter and $700/ month.”

Pamela: “How can people contact you?”

Lara: “Have a great idea? Go to our website and share it with us at Happy Docs Neighbors’ Clinic!”

A drawing of Chris and Lara planning an ideal clinic.

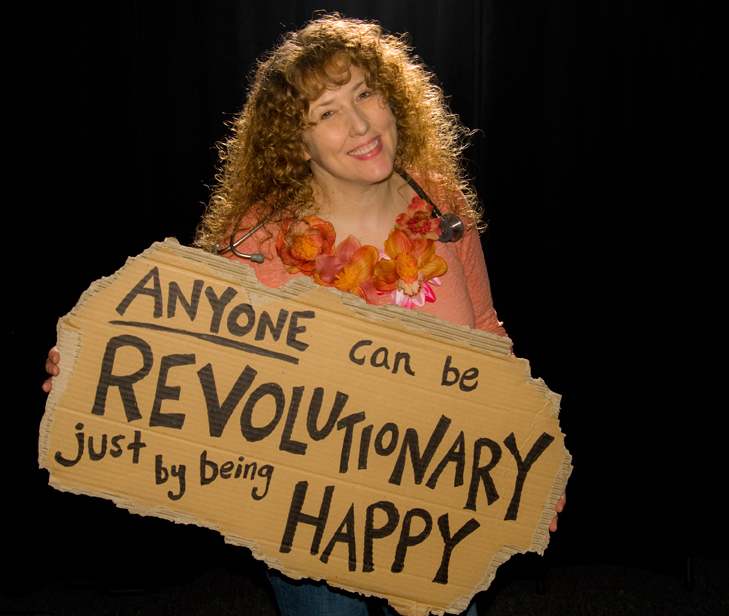

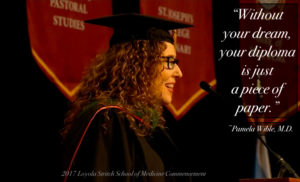

Pamela Wible, M.D. is a family physician in Eugene, Oregon and author of Pet Goats & Pap Smears, a book that documents how Oregonians pioneered the first community-designed ideal medical clinic in the nation. She trains physicians (and other health care workers) to lead town hall meetings and open ideal clinics at her biannual retreats.