A Florida community heals by celebrating the lives of 3 doctor suicide victims. Friends, family, & colleagues unite to share their love—and prevent future suicides. Listen in above to keynote and lively panel discussion. Full transcript and slides below.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I am so happy to be here. Mostly because I consider it a miracle—an act of God—that I even made it because coming from Oregon we just had our biggest snowstorm in 100 years just 24 hours before I was to board the plane. And it wasn’t just like a moment in time—it continued snowing all the way up until the point I was supposed to get out of my driveway. So like any good keynote speaker, I called the airport to get a shuttle and make sure I had my ride. And they were laughing at me. They told me, “Are you kidding? All of our cars are buried under snow. We can’t get them out of the airport parking lot.”

So that’s when I knew I was going to have to start digging my own car out. I started with a dust pan and a broom, a garden shovel and rake. Then we boiled hot water and poured it down the driveway and also my partner held a blow dryer, like some sort of thing from home depot, against the front of the car. Luckily we were one of the few homes with power. So this went on for hours and hours and hours. Finally my neighbors felt sorry for me and one guy did bring a snow shovel and helped us along.

So 2:00 am yesterday with a flashlight in my mouth, I’m trying to put chains on my Prius tires while my partner who never loses his temper starts raising his voice. “Sweetie!” kind of screaming, “Honey!” Luckily the snow absorbed all our voices so the neighbors didn’t wake up. I really had to get to the airport starting to move at 3:00 am because we could only travel at eight miles per hour because of all the downed trees and power lines that were hanging. I was kind of moving at the speed and the clearance of a lady bug in my Prius toward the airport. When I got to the airport I wasn’t at all sure I was going to actually leave in a plane, but my plane was the only one that was not canceled. Thank you United!

I didn’t even want to put that on Facebook or text it anywhere until I was officially in my seat 7A, at which point I did and I felt home free. But that’s when the announcements started coming on the plane—the engines were frozen. So they got a blow dryer out that was way bigger than the one held against my Prius. Took about an hour and then after that since you couldn’t see out of the plane window, they had to de-ice the entire outside of plane, which made the whole interior of the plane smell really weird—probably very toxic. Putting my life at risk trying to get here. I thought we were all set and the plane backed up from the gate and I was like awesome!

Until they made the announcement that they couldn’t go down the runway. We turned back around and went back to the gate. They told us all to get off the plane. And they announced operations had shut down at the airport—which meant the whole airport closed down.

Even if the airport shut down, I had determined I’d stay there until the time of my keynote until I’d get a plane—oh, and called my psychic friend LOL who told me she already saw me there speaking so I wasn’t too worried and knew it would somehow work out).

Luckily we had a female pilot who would not give up and so she somehow cleared this one little runway area and all the passengers were all like hovering around wondering what was going to happen. She the pilot tells everyone that she’s going to take the airplane for a trial run down the runway and if it worked she could come back and get us. She back up to the gate and told us all to get on.

We landed in San Francisco where the weather was rainy, windy, very hazardous and the other planes were delayed. So I went to sleep in a yoga room that I found in the corner there until I could get on a plane to Florida. So I just got here today after midnight. Let’s hear it for Sami from Volusia County Medical Society who picked me up in Orlando.

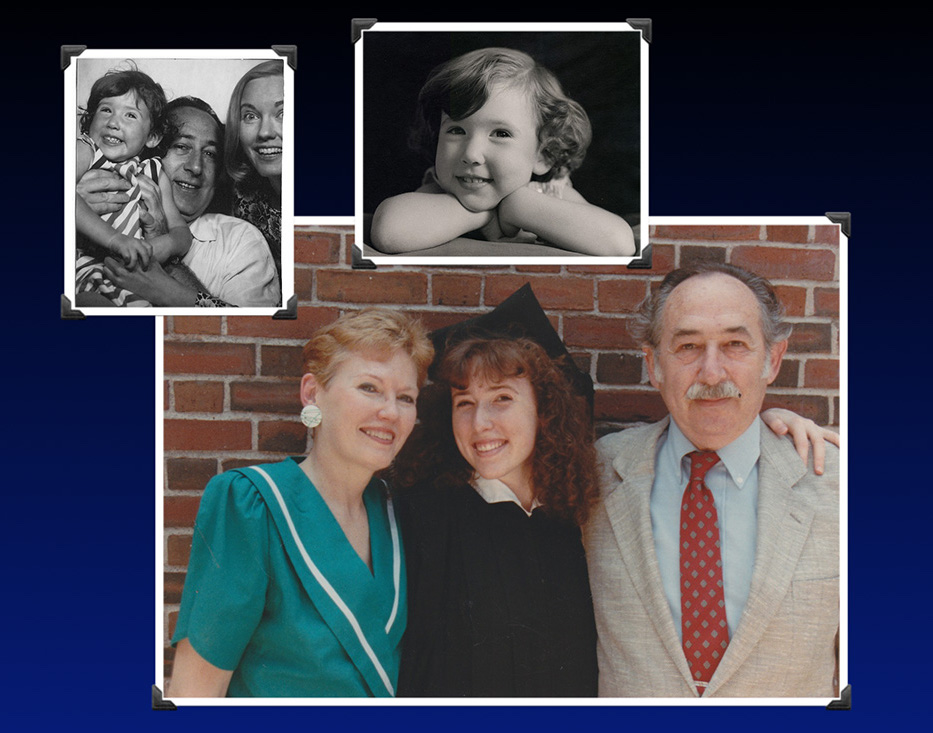

Reason why I feel like it was an act of God and a miracle is that I am here today to celebrate the life of Matt Wittman. Some things just can’t be stopped. Matt would have been a graduate at Florida State University College of Medicine this year, May 2019. And I have a few more pictures of Matt I want to share with you, beautiful soul that he is and I want to do a little experiment with you that my mom used to do with me when I was a little girl.

My mom was in her psychiatry residency when I was little and she never read me regular children’s books. She used to read me psychiatry journals and she used to stop at all the pharmaceutical ads and make me tell her a bed time story. Yeah, that’s what I had to do. This is what happens when your mother is a psychiatrist. Everything gets turned around like into all sorts of weird psyche games on you cause she liked to analyze how my brain was developing. So I had to look at these 1970s Valium ads with freaked out, housewives trying to grab their Valium and Mom made me tell her what was going on in their lives. So I got really good at looking in people’s eyes and trying to figure out what was really going on behind the smile.

So I just want you to look at Matt. I want you to see he’s such a genuine person and really steady. He strikes me as a steady, helpful, sweet man. And sometimes when I look at this now, I feel like I see maybe a little bit of sadness in the background. Matt is a true friend. He really is one of those people who … he was bringing food to the homeless, by his apartment. Always helping somebody else.

Here he is you can see him graduating from college. And these are his parents—Julie and his dad Clay. And of course they look very proud and happy. I have a letter I’d like to read from his parents. I think this will help you understand a little bit about the big why. That’s what we’re always left with when these suicides happen.

Dear Medical Student, I can’t imagine the stress and anxiety that you feel right now. However, I can certainly understand how you may feel, given the demands of Medical School. We lost our son, Matt, a second-year Medical Student, to suicide in February of 2017. He left this world in complete despair, hopelessness, and, in his mind, nowhere to turn for help. Unfortunately for all of us, he didn’t share these feelings with anybody: not his classmates, his church friends, or his parents. Only after we met the Dean of the medical college after his death did we realize he had failed his second class, and was in jeopardy of not being allowed to take Step one of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) in the coming months. Also, we found out in his short time in medical school that he had amassed $100,000 in student load debt. All of these factors certainly weighed heavily on him.

About our son. ALL he wanted to be in life was a physician. From about the age of 13 that is all he wanted. He had a less than stellar MCAT, and he tried for three years to get into medical school. He was finally accepted due to his practical experience as a crisis line counselor and EMT. Unfortunately, he refused to even talk about a plan B as he was applying for the second and third year for a slot in medical school. He refused to discuss a plan B after he started school and was not doing well. In the summer before his death he announced he wasn’t going to call us on Sunday as was the practice in our family. In fact, he told us he might call us once in a few months. Those months went by with one call from him, then the dreaded call in February informing us of his suicide. Matt did not discuss his challenges and his apparent increasing depression with anybody. When we met his classmates at the memorial, they looked to us for information as to how and why this could happen; none of them had any idea. Same when we met with his church group and the folks he spent time with on the weekends; none of them had any idea that Matt was struggling and in such despair.

So why am I telling you the story of our son? I want you to know that there ARE people who LOVE you, people who WANT to hear from you, especially in tough times. I want to make sure you understand that WE are there for you! We may not know you, but we ARE there for you. We had so wished our son had confided in us regarding his struggles, if not just to give us the chance to give him some kind words and hope for his future. We were not so fortunate.

There are many resources for you if you are feeling the stress and anxiety that our son did. We would recommend, as we told my son’s classmates at his memorial, that you please call your parents, call your siblings–reconnect with them if you have been too busy to do so in the past. Share your thoughts with them. Talk to your classmates: You may be surprised to find some of them experiencing the same challenges. If you are active in a church, mosque, or synagogue, talk to your pastor or church elder–you may be surprised that you are NOT the first student with your challenges.

Seek out medical help. Our son was clearly depressed, but he kept it from everyone. He couldn’t overcome the stigma of a medical professional seeking mental health counseling. That stigma is OVER. I know Deans of medical colleges that are actively trying to get the word out to their students to not be afraid to seek counseling, as nobody should bear the burdens of medical school by themselves.

You are NOT alone!

Julie Wittman

Wittman@hotmail.com

Clay is here with us today in the front row—and we have some requests to honor Matt Wittman.

We ask that you please have a plan B because successful people know how to quit and don’t isolate from friends and family and classmates and please share your feelings with someone. Seek mental health care as soon as possible. If you’re depressed and realize your life is more important than any career and know that you are loved.

So why do we care?

I want to share a picture of me at my graduation from college. Just kind of like the picture you saw of Matt and his parents. Both my parents are physicians and here we are.

You can see my dad’s kind of the absent minded professor type pathologist. My mom’s a psychiatrist. You never know what she’s really thinking. And there’s me when I’m little. And so when you look in my eyes, you can see I’m pretty much the same as I’ve always been from when I popped out of the chute. I’ve always had this ready to go, excited, can’t-wait-for-what’s-next-in-life attitude. Now I want you to see the next slide.

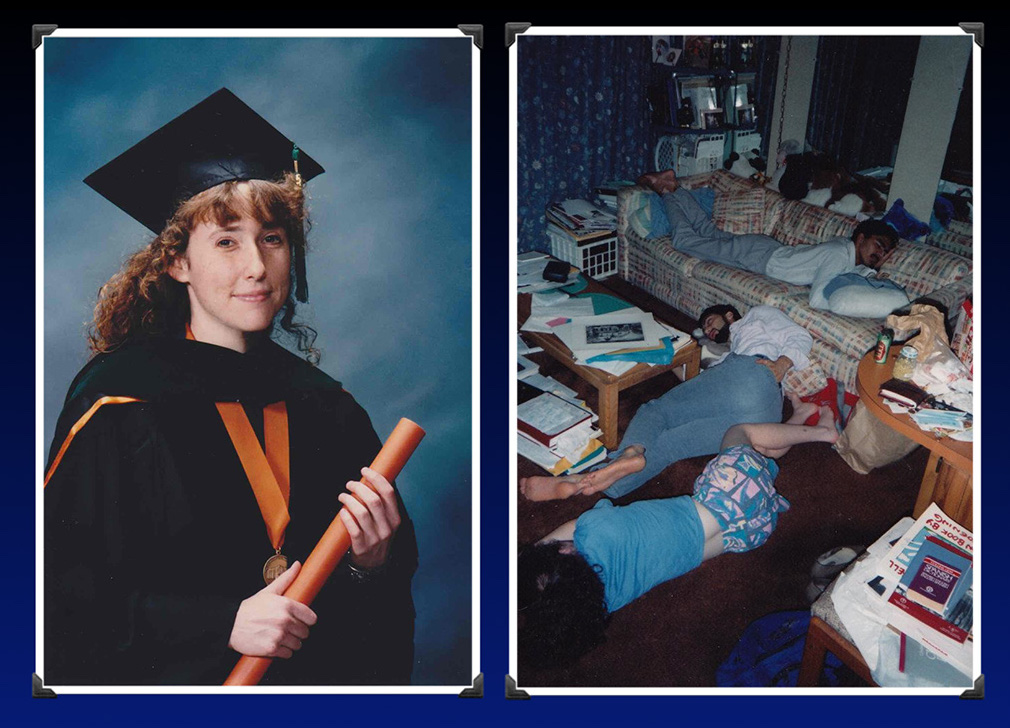

What happened to me in medical school? So there’s one picture of me graduating and one during medical school. So the one of me graduating, you can see I want you to just notice using the same technique my mother put me through with pharmaceutical ads as a child. Notice that I look different when I’m graduating medical school. I don’t have that same exuberant, I-can’t-wait-for-life attitude. What I look like to me is somebody who survived a war. And I am trying my best to smile because you’re supposed to smile when you graduate. Okay. That’s how I look in that picture and the reason why I look that way. You can see the next picture on there where I’m laying on the floor. That’s what I remember from medical school. I don’t remember anything that happened in the world for four years. All I remember is collapsing on the floor underneath all sorts of books and things that I had to do and I always felt behind.

The person next to me on the floor I dated for three years in medical school and he actually died by suicide. And that is the only picture that I have of us together in medical school—and we dated for three years! So I think that’s significant when your life is so distorted that this is your experience for a prolonged period of time. It does feel like a war.

He didn’t die while we were dating. He died when he was a physician married to somebody else. Just making that clear. Because both men that I dated in medical school died by suicide and people are like, oh, you must be like a black widow. Like you kill all the men you date. I just want to say it’s really not me. It’s medical school and other things. I’m innocent. I just loved them while they were here. They died later while practicing medicine while married to other women.

I really thought I was the only suicidal physician and I was really depressed during medical school, especially my first year but I didn’t becomes suicidal until I finished my training and I was stuck in these big assembly line, big-box clinics and I felt like, oh my gosh. I went through 24 years of school from kindergarten straight through and a family medicine residency to just be a seven minute factory worker, physician in a assembly line clinic. It was terrible. This is how I looked when I was suicidal.

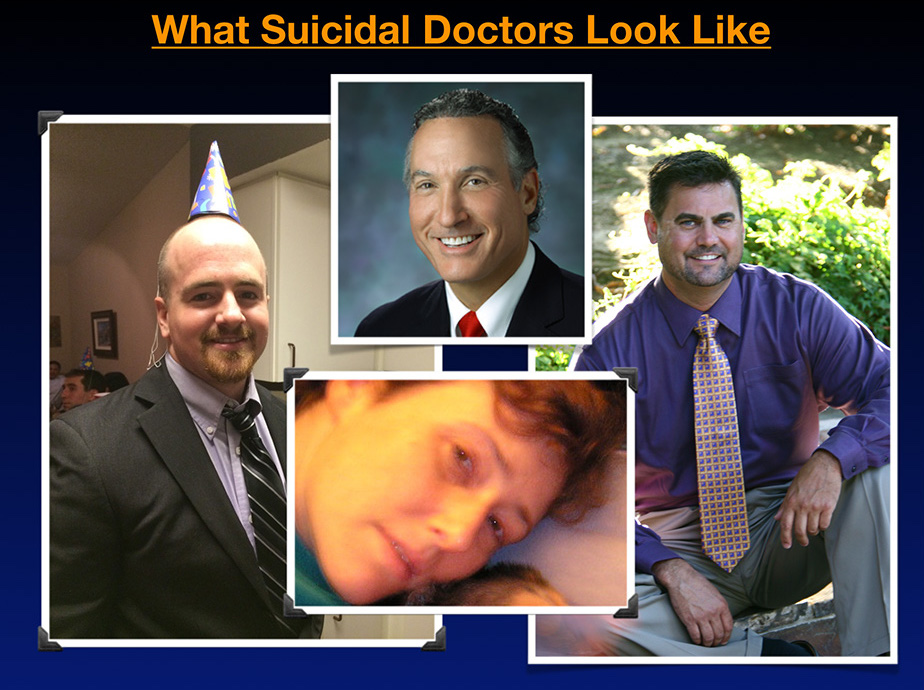

I just want you to see what a suicidal physician really looks like. This is one of the problems. We never understand who’s suicidal cause they’re all fake smiling during the day. And if you fake smile during the day, nobody can tell that you’re suffering. So I’m just trying to show that I’m certainly sure before physicians die by suicide they look more like me when I was suicidal. I’ve never really shared this photo publicly with anyone. It’s not like a great one to put on your Facebook page or whatever. But this is the truth.

To solve this crisis we need to reveal of our true feelings. Otherwise people are in the dark and they think that we’re just “happy.”

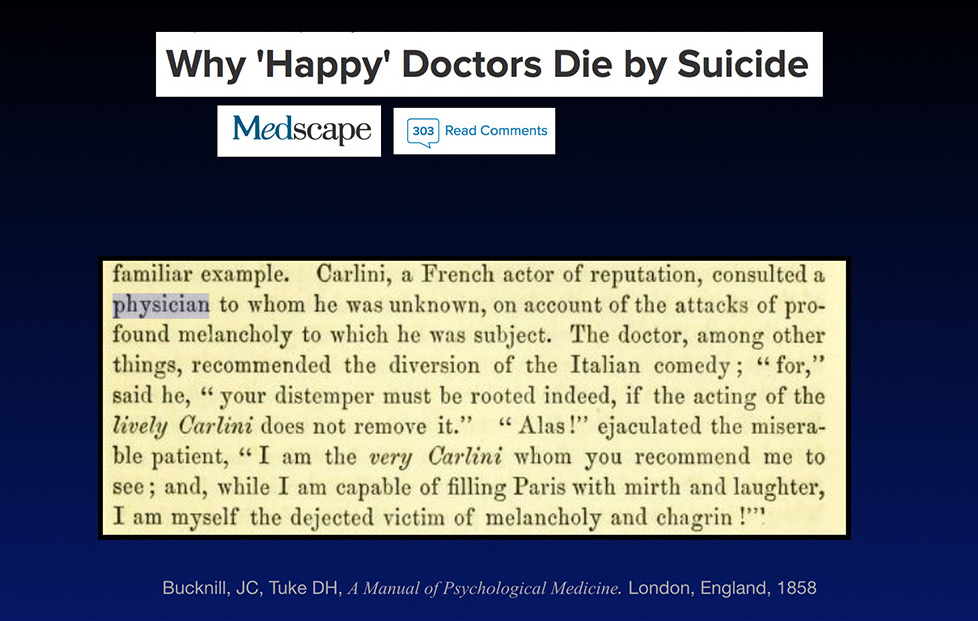

So the big shock for me is that I thought I was the only one. I didn’t know that this was a crisis that has been reported since 1858 when it was first discovered that doctors die by a high suicide rate and more than 160 years later here we are just like in the beginning baby stages of figuring out this is an issue because we are hiding the doctor suicide crisis through centuries of censorship.

So the root causes have not even been really identified or addressed because we’re hiding the situation. Physician suicide is most definitely a public health crisis because we lose at least 400 physicians per year in the US and that’s the equivalent of an entire medical school just wiped off the face of the earth every year. Should that now draw somebody’s attention and interest?

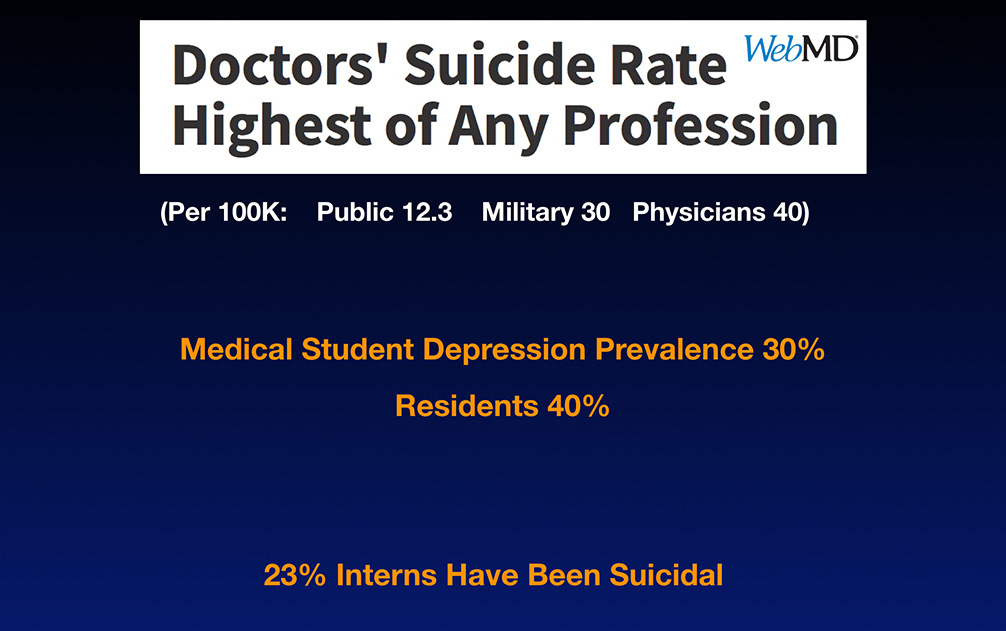

Because it’s such a scary taboo topic, nobody wants to discuss it. Now think about each physician with approximately 2000 to 3000 patients that they care for in their patient panel. Do the math. That’s a million Americans every year losing their doctors to suicide, which is huge. That’s a public health crisis. Right Recently it’s been reported we have the highest suicide rate of any profession. Does that make any sense at all?

You assume this is a profession where we’re all about wellness, but actually if you look at per 100,000 citizens in the US, the general public dies by suicide at 12.3 per 100,000. The military at 30 per 100,000 and physicians up to around 40 per 100,000. That’s not even including the medical students—and that number is still considered under reported for a variety of reasons. Mostly because the fox is guarding the hen house or whatever. We’re filling out the death certificates and not really coding our friends’ suicides properly. We as medical professionals are complicit in hiding these suicides, yet as scientists we’re in charge of revealing the data.

So the real accurate statistics might be worse than this. Medical student depression prevalence is about 30%, but I feel like most people in my medical school class were depressed at some point and so I just don’t think they’re telling the truth when they say it’s 30% because I think medical students are scared to even reveal this on any standardized—even anonymous—form that they might be depressed and residents, 40% are depressed according to various articles. And 23% of interns have had suicidal thoughts.

Okay. So this is an issue that’s not just isolated. This is an issue related to our profession and our training. And I think once we can understand that we can start to change things.

This picture, the next one is actually in my house, in my home business office. I have an entire wall now covered and photos of medical students and physicians that have been lost to suicide.

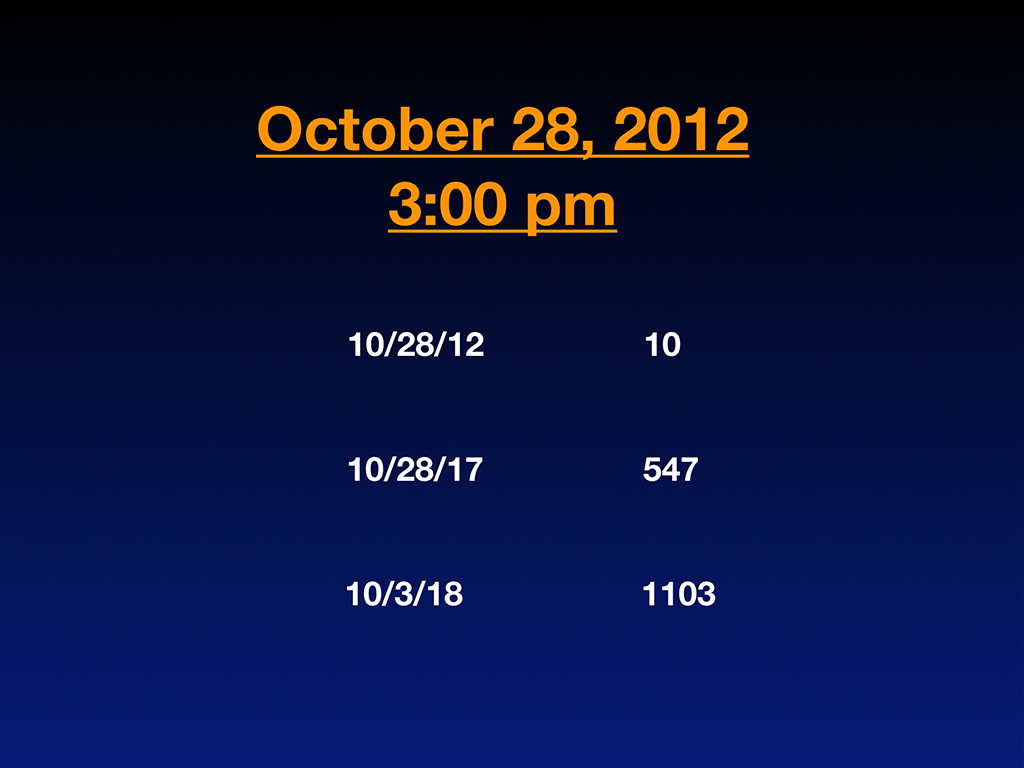

I have been working on this since 2012 when I thought I was the only suicidal doctor in the world. Who knew that there were all these others? And the number grows day by day—each day that we don’t address this as a real public health crisis, the numbers keep growing. And so I wanted to share how I got involved in this. It was October 28th, 2012 at 3:00 PM when I was sitting at the memorial for the third physician that we lost to suicide in my pretty small, sweet town, Eugene, Oregon where everyone holds hands, sings Kumbaya and goes to the farmer’s markets together. It’s the sweetest town that you could think of and they even help you when you’re stuck in a snowstorm. Your neighbors come with snow shovels and it’s just a sweet place.

Sitting there at this memorial in the second row behind his five children and his wife, I started counting, nobody could figure out why these people had died, especially at this memorial. Why did this guy die? He was, you know, these are not fringe characters. They’re best-rated doctors, top in their specialty, the prime of their careers. And suddenly he shot himself in the middle of a public park in the middle of the day. Why did he do that? And they never said suicide out loud at the memorial, which is upsetting to me because how are we going to heal from this and figure it out if we can’t even say it out loud?

Where would we be with diabetes if we whispered in the bathroom stalls about neuropathy because we can’t say it out loud? I mean, just think if we applied this sort of behavior to any other medical condition, we would be in the dark ages, which is where we’re coming out of now.

I just actually sat there, started counting the number of doctors who died by suicide. And at that time, I knew both men that I dated in medical school were dead, but nobody had told me how they died. And I just sort of started putting it all together. You know when you have the light bulb moment when you’re like, wait a minute, wait, it isn’t just this guy. Wait, let me start counting. . .

When I started counting, I knew 10 doctors that died by suicide or under highly suspicious circumstances that I thought were suicides that I needed to check out to confirm. And that’s quite a lot considering I was in my early forties. Five years later I end up with a registry with 547 names because I guess I became known on the Internet as the person that wants to talk about this. So everyone was submitting to me all their relatives and neighbors and all that.

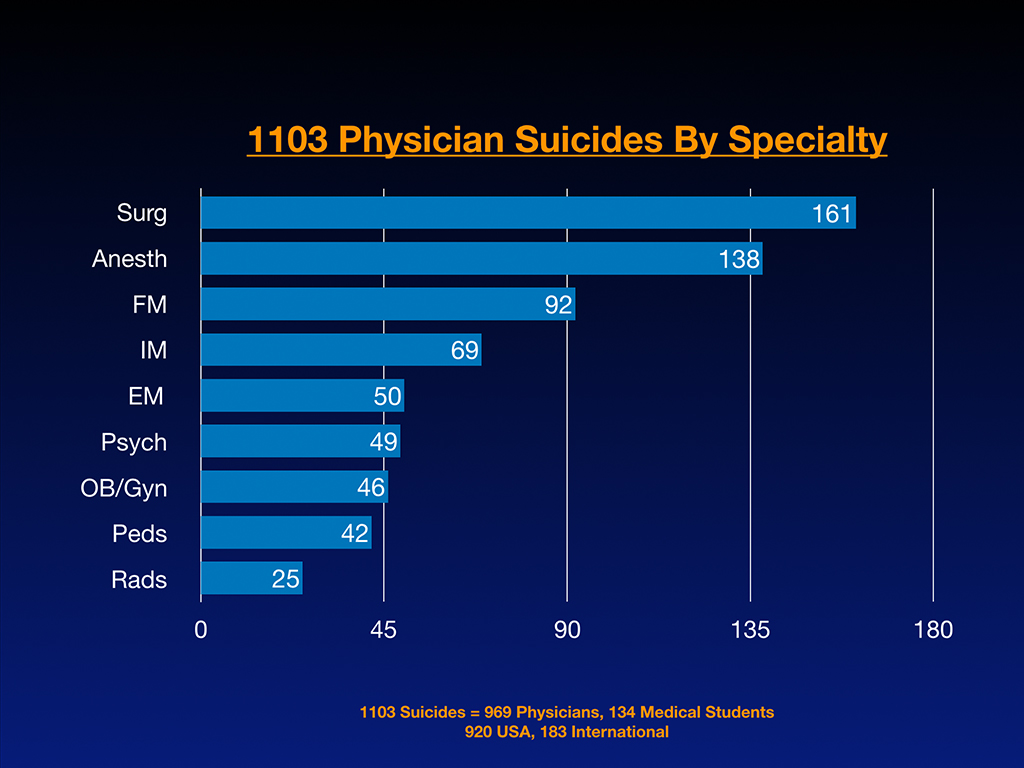

By late last year, I had 1,103 on my registry. I keep a registry by name, their date of death, their age, specialty, the extenuating circumstances and locations.

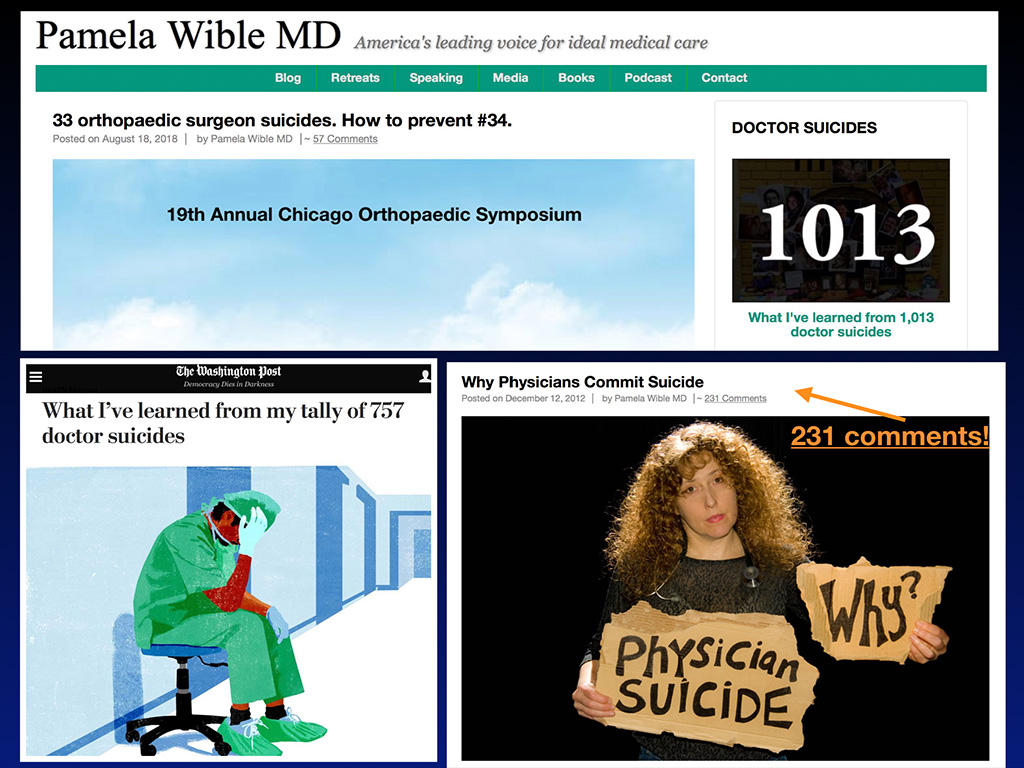

So now I actually have 1,208 on my physician suicide registry. And the next slide you can see, this is just my blog and I just became so fascinated and disturbed by this that I couldn’t stop talking about it or writing about it. Oh by the way, so this blog that I was working on since 2011, March. I don’t think anyone ever read my blog. I don’t think anyone cared who I was. I think I just wrote happy stories about being a happy doctor cause I had opened my own clinic. So like Delicia I was really happy in my own office and I didn’t quite realize until eight years later that that other doctors were suicidal.

All of a sudden I wrote this blog about doctor suicide and got 231 comments. I was like, “Whoa, I’ve never had a comment on my blog before in my life.” What is going on? The comments weren’t just like, “You go girl, like keep talking about it.” The comments were like, “I want to tell you about my son who died by suicide” and the entry read like a eulogy. Wow, these are some really intense comments on my blog. And so I felt like I just had to keep going.

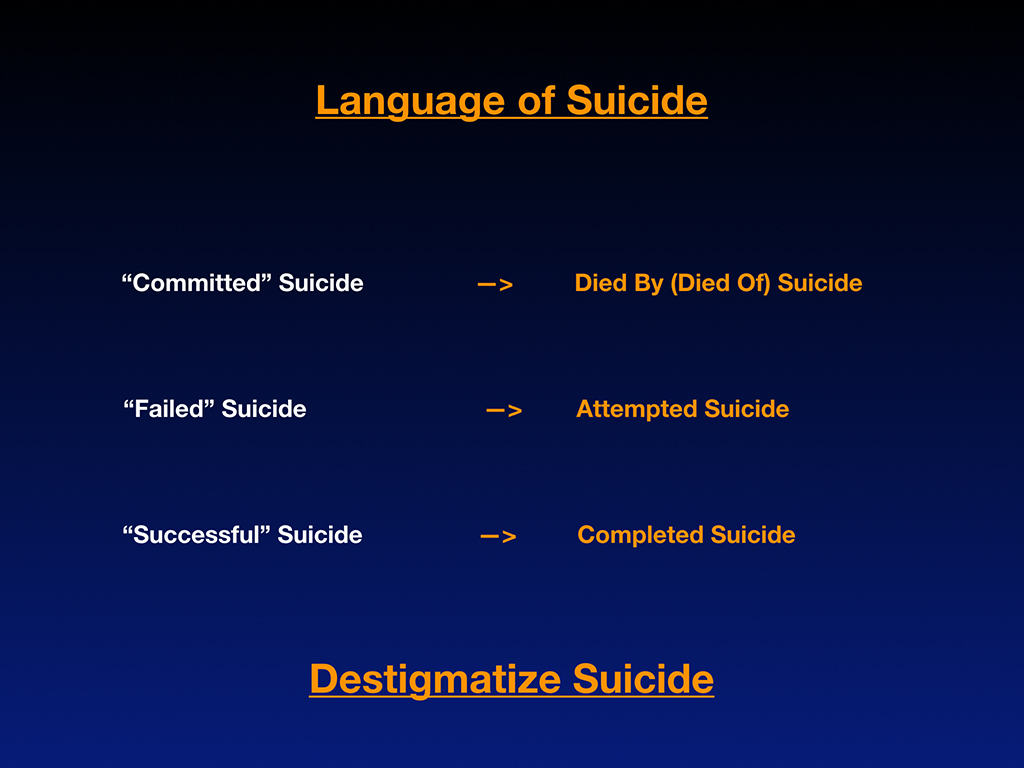

So I guess you could say I’m the leading voice on physician suicide prevention and so I’m going to share some statistics about suicide, but before we go into it I want to just discuss the language of suicide because suicide is such a secret and so taboo we don’t really know how to talk about suicide. And so I just want to share three things that we can do differently.

One is to stop saying committed suicide because committed makes it sound like a burglary or rape or a crime or something. And it used to be considered a crime, actually. But it’s really just a person who’s suffering and feels hopeless and doesn’t know how to get out of the pain. And the only thing they can think of is to stop breathing as a solution. And so it would be better to just say died by or died of suicide, just like died by pneumonia, died of from a car accident, that sort of thing. That way there’s no overlay of blame on the victim, which makes it challenging.

And then there’s this thing that we used to say, called a failed suicide, which is, I guess when you try to die by suicide and you survive, well, how could that be a failure? You’re still here. So let’s just call that an attempted suicide and you survived, thank God. Right? Don’t say failed suicide.

And then there’s this thing called a successful suicide. How is it ever successful if you’re 20 or 30 years old and you just killed yourself? That is never success. Don’t say successful suicide. We should call that a completed suicide.

So if we could just change the language in these three ways—just these three simple things could help us to start addressing suicide without so much stigma that we’re injecting through language.

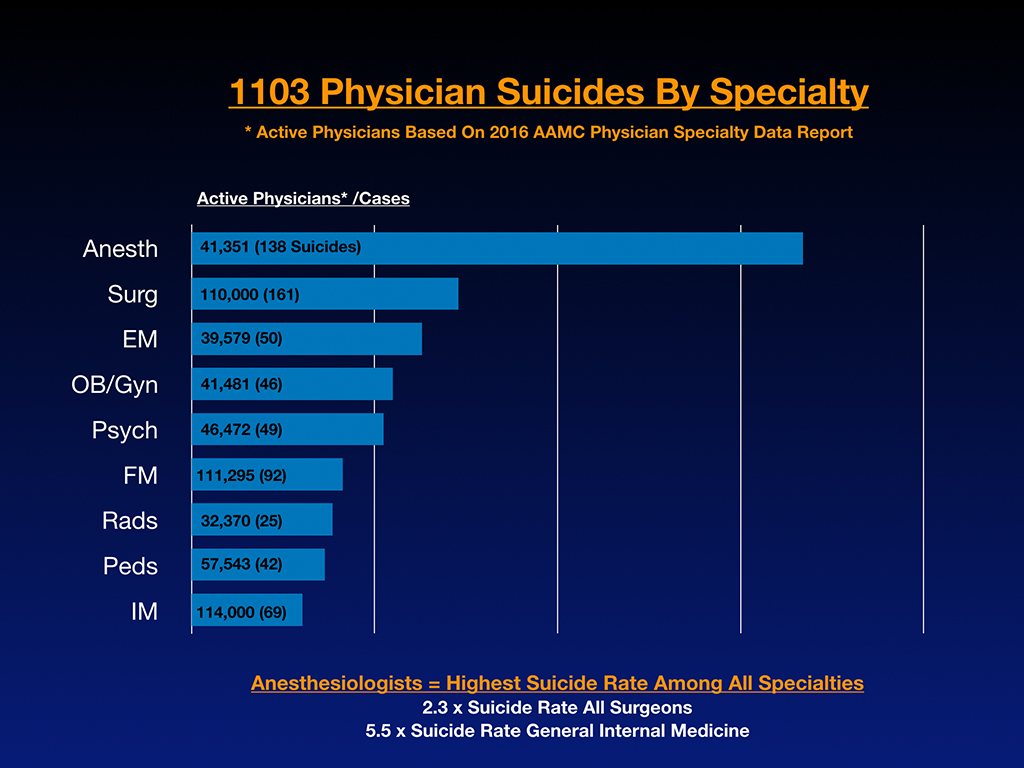

Now I want to share the results of analyzing the first 1,103 physician suicides by specialty that have come to me and in those 1,103, 969 are physicians, 134 are medical students and 920 are from the US but I also get them submitted from overseas. So 183 are international and India is a hotbed for this, by the way. And the UK also has their fair share and so does Nigeria, even though they act like there’s not a problem there. Australia, South Africa, I have some coming from all over the place and these are just submitted to me from people who run across my writing. So it’s very organic. It’s not like super scientific. This is just like whoever emails me and wants to share that they lost somebody to suicide. But it’s very interesting, the breakdown of the first 1,103 and that there’s a lot of surgeons and anesthesiologists and then you know, you can see like the raw numbers there out of the 1,103, but the next slide is really fascinating because that’s where I compared the number of cases I received with the active physicians per specialty. So we could start to see which specialty is really the winner in a game you never want to win.

Anesthesiologists are friggin’ off the charts with suicide. Just my 1,103 sample, which is probably the best sample we have going. Nobody seems to be taking a huge interest in this. I always thought psychiatrists had the highest rate. I had no idea, even a few years into this. And so I started analyzing by specialty what was really going on here. I think what clued me in that anesthesia was probably ahead is I was getting emails like this: “Hey, I’m an anesthesiologist and I lost eight of my colleagues to suicide.” I’ve never gotten a similar email from a pediatrician or a family medicine doctor or anyone else. And I’ve got several, a woman from Brazil who’s an anesthesiologist told me she lost six or seven colleagues to suicide and so I had a hunch, right. Oh I think anesthesia is way ahead on this. But now when I got the numbers down, it’s startling because anesthesiologists are dying by suicide at 2.3 times the rate of surgeons, which is the next highest specialty and 5.5 times more likely to die by suicide than general internal medicine.

Why is it important to discuss this? Medicine is all about informed consent. I just spoke at a pre-health conference last week. We are not allowing young people informed consent they deserve before they end up with a $100,000 of loans on a career path that may be high risk for them. It is only fair.

I mean we even have on cigarettes a warning from the surgeon general that you could get lung cancer. People who’ve already had suicide attempts in high school, who’ve already have panic attacks in college, who already have had been in drug rehab because of personal issues with addiction. Should absolutely know before pursuing anesthesia, surgery and emergency medicine, like FYI—Danger zone. There are reasons why you might choose preventive health or internal medicine or maybe something else or not even go to medical school. There’s other things you could do that are fun and exciting that help and heal people.

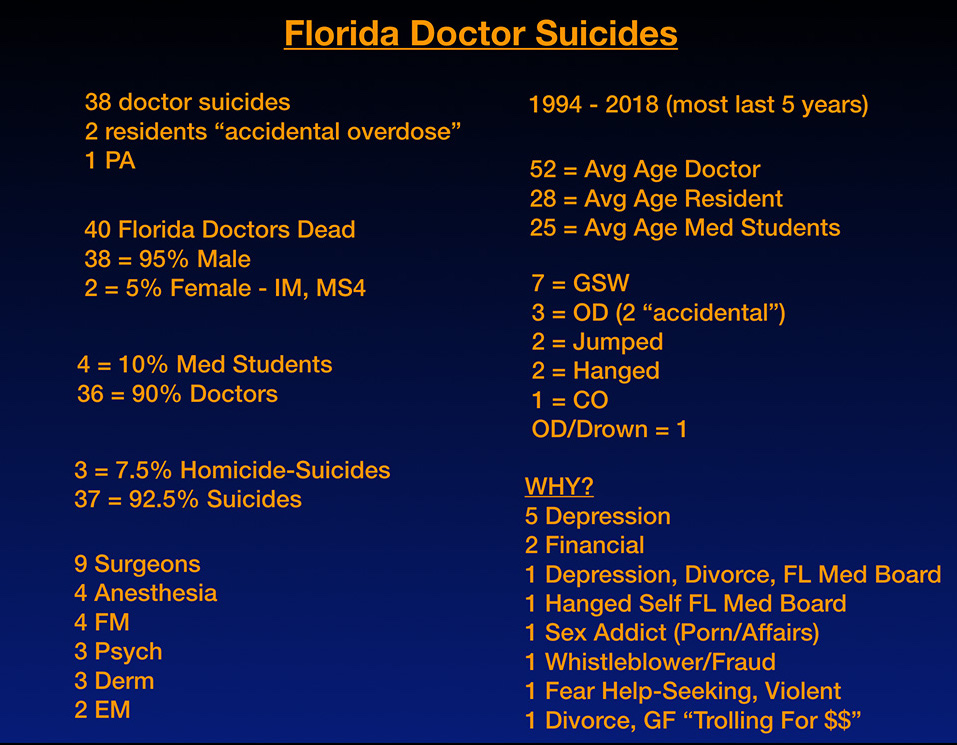

During the snowstorm while sleeping in the yoga room at the airport, I decided to pull out the Florida cases and just share a little bit of Florida physician suicide information with you all. So in Florida, I have 38 doctor suicides on my list of 1,208 and two of them are residents that are considered “accidental” overdoses, which I don’t believe for a minute. But I did speak with one of the mothers on the phone a while back and she was very insistent it was accidental overdose. So I do have the separate category called “suspicious for suicide” that I have them down in there. So they’re not really on my 1,208 actually, they’re in a separate little section for suspicious.

Regarding “accidental” overdose for a physician—you must be a really terrible physician if you don’t understand the lethal dose of Tylenol. Come on. If you were Michael Jackson, Prince, whoever else, and you died of an accidental overdose alone in your house playing with drugs, I could maybe believe that because you’re a musician. But if you dose drugs for a living, like that’s what you’ve been studying your whole life, you’ve been through so many pharmacology courses, I really think there’s absolutely no way it was a 100% accidental overdose.

It’s either a 100% intentional overdose or it’s a two to 99% Russian roulette situation that nobody knows except the person who’s dead. So we can’t ask them. But I really think it’s important for us to stop putting a whole bunch of doctors in the category of accidental overdose. If it’s a car accident, maybe, but still I’m sort of thinking if they’re a resident, I’m still questioning it. I think any death of a doctor under the age of 50, for sure, has to be suicide until proven otherwise, in my opinion. But I just want to point out my perspective on accidental overdose. There’s also one Florida PA, by the way. Sometimes people are submitting veterinarians and others to my list. So I have a separate list for other health professionals.

Out of the 40 Florida doctors who are dead on my list, this is really interesting, 38 of them or 95% are male. Now that is really different than the rest of the country where it’s more like 75% are male. Okay? So I don’t know what’s going on there. I’m just pointing it out. I mean, it’s a small sample size, but worth discussing. Two of them are female and one of those was internal medicine and one was a fourth year medical student. Four of the 40 are medical students. That’s 10% medical students and 36 were physicians, 90%. And what also is outlier, again, it’s a small sample size, but three of these were homicide-suicides in which two killed their spouse and one jumped off the balcony with his two children (while his wife was in the bathroom at a hotel). I don’t know that he lived in Florida, but he definitely died in Florida.

Physicians are so caring and healing and loving humanitarians—they pretty much martyr themselves to save others. So it is very unusual, I think, compared to other groups of people to have homicide-suicides. 37 of these were just pure suicides. So 92.5% of the Florida cases that I have were just pure suicides and how they break down by specialty. I don’t always have all the specialties. And because I did this sort of at an airport in the middle of a snowstorm, I didn’t really dig deep through all my files. I could have gotten more detail, but this is just a little thumbnail sketch of what’s going on in Florida according to my list. Nine are surgeons. Four are anesthesiologists. Four are family medicine. Three are psych. Three are derm and two are emergency medicine. And then there’s a scattering of everyone else.

These are mostly in the past five years. But the earliest case I have from Florida is from 1994. The average age of a doctor in Florida who dies by suicide is 52. The average age of a resident who dies by suicide, they were both 28 (and these are the “accidental” overdose crowd). Average age of a med student in Florida who dies by suicide is 25.

Method: Seven are gunshot wounds. So that predominates. With men, that’s a popular way to go on the west coast and in places where guns are accessible. Okay? Which I think is the case in Florida. Stand your ground state. Right? Like everyone can get guns here as far as I understand. I’m not pro or anti gun. I’m just stating the facts that we’re using guns on ourselves. Three were overdoses. Two of them are accidental. Although there’s one that was carbon monoxide in the garage. I guess you could consider that overdose, but I put that separately. Two jumped. Two hanged themselves. One was an overdose in combination with walking into the ocean. These are the ones that I knew about. Again, I often don’t have complete data on people because sometimes the people reporting to me are like, “I don’t really know how he died by suicide.”

So now why they died. Depression is number one, untreated depression. Five of them, I know, were untreated depression. Two were having financial issues. One was having depression in the middle of a divorce and had trouble with the Florida Medical Board. Another one hanged himself right outside the Florida Medical Board because he couldn’t get his license after three years, I think being locked in a PHP or some sort of a program for … often when physicians have problems, they’re sent into these punitive situations where they’re punished as a way to cure them or something, which does not help. It would be better to get actual health care and not be punished. But I think this gentleman obviously felt punished and he felt punished by the Florida Medical Board, so he chose to die right in front of the Florida Medical Board.

One was having sexual addiction problems with porn and affairs. But again, I think that’s a late stage impact of some of the earlier wounds to us during our medical training. And maybe if he had had help sooner for PTSD or whatever, he wouldn’t be all over the place with affairs and porn. One was a whistleblower and fraud related. One had a fear of help seeking. I really had a very interesting conversation with this man’s wife because she said he was becoming violent. He was one of the ones that jumped, not the homicide-suicide. But she wanted him to get help, but he was absolutely afraid of seeking help because it would kill this career. So he chose to kill himself instead of get help because this is the situation we’re in. We’re not making it easy for people to get help. We’re making it easy for people to be punished often. Another one was a divorce with a girlfriend trolling for money.

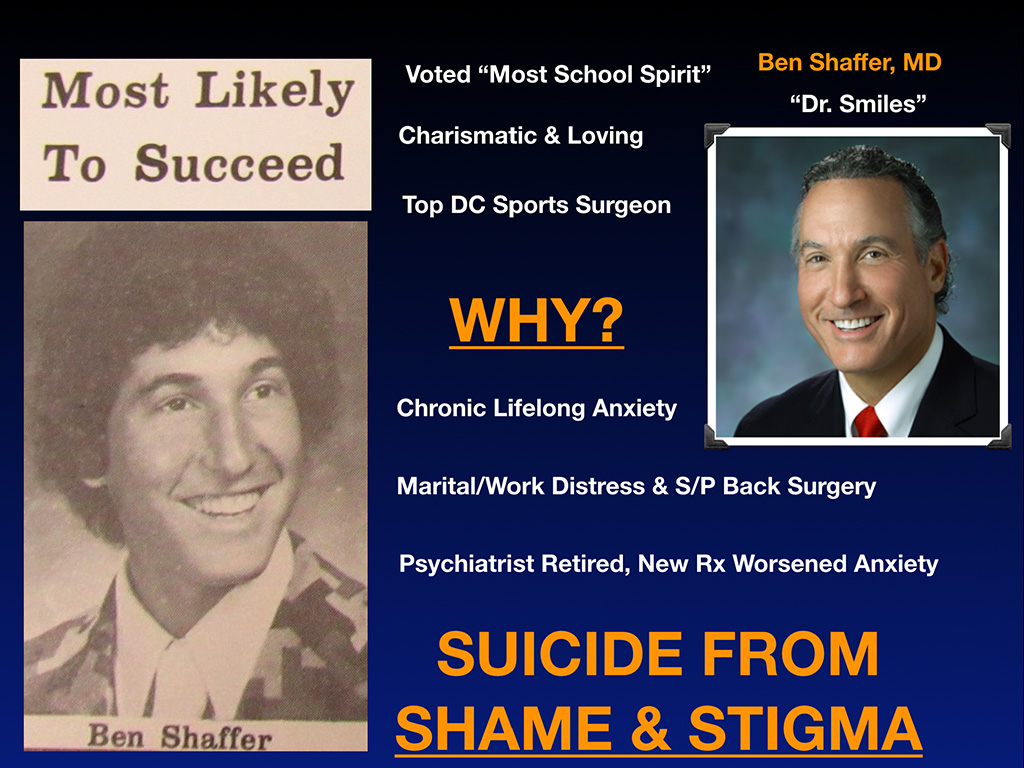

Now I want to share three actual cases from Florida just because sometimes graphs and charts aren’t so memorable as real people. So the next slide you can see a beautiful man named Ben Shaffer. Such a frigging cool guy. You can see another picture of him. They called him Dr. Smiles because he’s just such a happy, cool guy. He was voted most school spirit like in seventh grade and he’s such a charismatic, loving guy. He went to Florida, I think, for college and med school, although he did die in Washington D.C. He was a top D.C. Sports surgeon. Why did he die by suicide? Well, he had chronic lifelong anxiety.

Now look at his picture. This is the picture of somebody who’s really happy, but chronically anxious. Just FYI, I don’t know whether you can tell that he has chronic lifelong anxiety. These are the things that we’re not often picking up when people are cracking jokes and looking invincible. But he had, of course, some marital and work distress. If you don’t have marital and work distress in medicine, I don’t know. You’re probably the outlier. When you’re working a hundred hours a week, it’s got to affect your marriage. And he was recovering from back surgery. And his psychiatrist, this was the thing that really sent him over the edge, had retired and he was placed on new medication, which was not working. In fact, worsening his anxiety, insomnia. And he did not want to ruin his reputation.

So he chose to die instead of ruin his reputation. In his mind, he didn’t want other people like pro athletes and teams in Washington D.C. to know he was suffering. He didn’t want them to find out that he had, God forbid, a mental health issue. So instead of revealing this, he hanged himself on May 20th, 2015 on a bookcase in his house after driving his son to school. And he died because of shame and stigma, which is so very sad and unnecessary.

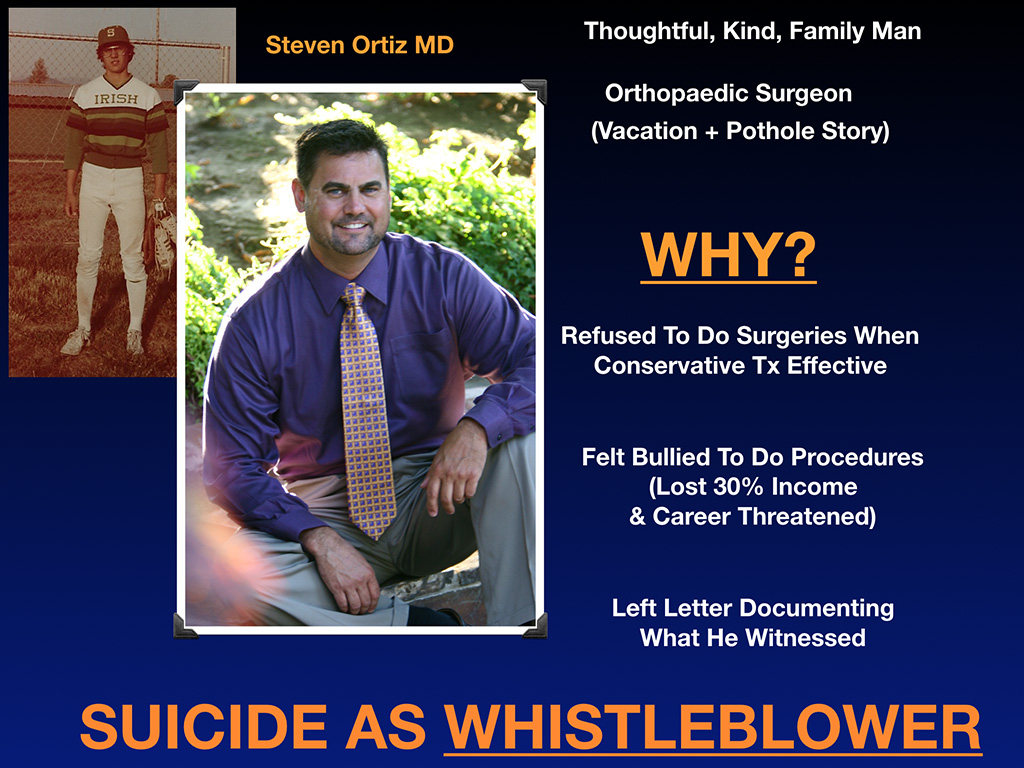

The next gentleman is Dr. Steven Ortiz. Such a cool guy. He grew up in Eugene, Oregon down the street from me and went to Sheldon High School. Such a thoughtful, kind, family man, orthopedic surgeon. I just want to share this little cool story about him. He went on vacation once, probably only once. He’s such a workaholic. But during his vacation, one of his patients became sick. So he flew home early to take care of his patient. What kind of doctor does that? I’ve been told I’m like Mother Teresa—and I’ve never done that! You know what I mean? Like that’s pretty hard core.

Check this out—there’s a bunch of potholes outside of this Spring Hill Hospital where he worked. And I guess as a spine surgeon, you don’t really want your patients bouncing up and down potholes. He talked to the hospital and they didn’t want to fix them or they were slow to fix it. So yeah. He used to be in construction before medicine, so he went to the hardware store and just got to work early and fixed all the potholes in the parking lot since nobody else would do it. That’s before he went into a full day of surgery. Is that a cool doctor or what? Like fixing potholes before surgery? I just want you to understand his character. You can see in his face he’s a steady, good guy. He really cares.

So why did he die? He refused to do surgeries when conservative treatment was effective. And as you know, surgeries bring in a lot of money for hospitals, but he felt bullied to do more surgeries or do more procedures than was necessary or something—or withhold surgeries from other patients. And he wouldn’t play this little game that goes on. I know many of you who are high-dollar volume specialists know what I’m talking about. And so he lost 30% of his income. His career was threatened and he left a letter documenting what he witnessed and then went outside into the parking lot, where he fixed the pothole, and sat in his truck and shot himself in the heart on February 8th, 2017. So he died by suicide as a whistleblower.

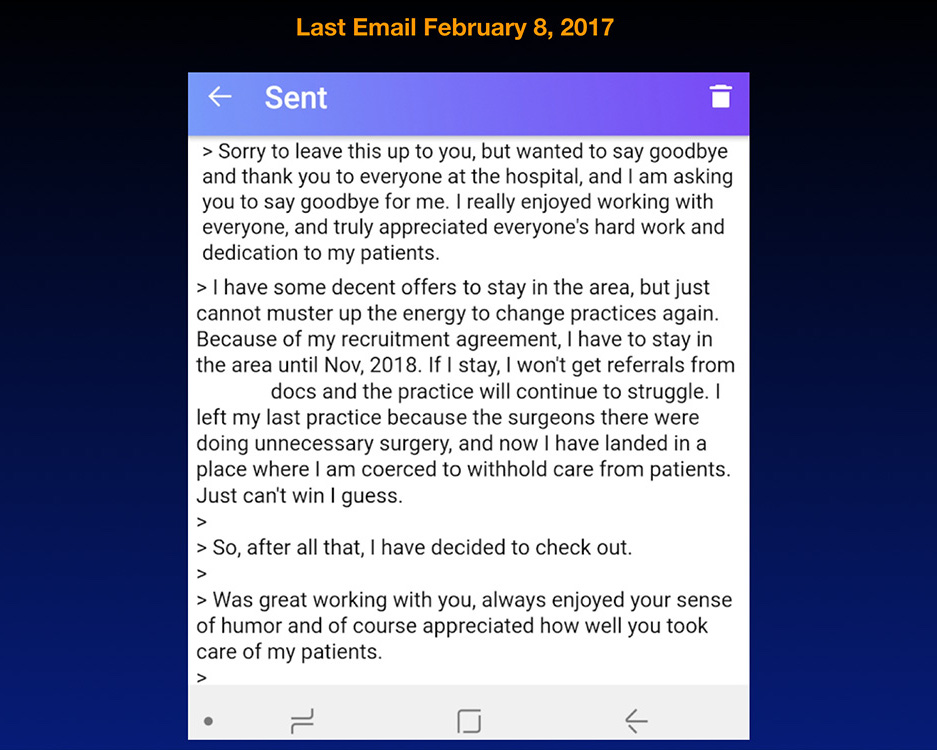

I think he was just exhausted. He didn’t know how to go on and he wanted people to know why he died. So on the next slide, you can see this was actually the very last email he sent on February 8th, 2017:

Physicians have a great work ethic until their last breath, generally. That’s the last thing that goes, which is why you can’t determine who’s suicidal because they’re shining stars at work right up until they grab their gun. Okay? Another orthopedic surgeon went and got a rope on the way to his office because he was going to hang himself at work, but he first wanted to finish dictating his charts. I’m just telling you, this is how doctors think. So if you see somebody going to work on Sunday finishing up their work, they could be suicidal. Who knows? They have a rope their car. I mean, how are we going to figure this out?

By the way, I interviewed a lot of male physicians who survived their suicide attempts (because this is still predominantly a male situation). And I asked them how long between when you decided you were finally going to end your life and you grab the pills or took the gun or whatever? They said three to five minutes. This is an impulsive move at the end. And I truly feel like every one of these instances, there were hundreds of missed opportunities that we could have helped them, especially if they would have made it known they were suffering.

I want to introduce you to our special guest today—Sherry Cleveland. She’s in the front row. She’s the one who received that email from Steven Ortiz and we’ll hear from her and Clay later in our panel discussion.

Another little tidbit which I found interesting. “Why happy doctors die by suicide” was an article that I wrote devoted to Ben Shaffer and became one of the top 10 on Medscape last year with 303 comments. So I think I’ve touched a nerve. And something that I mentioned in that article that really touched a nerve in me, came from that book from 1858, the book that was the one where the very first report of high suicide rates among physicians was first noted.

So this is the situation. We spend so much time helping and healing others and cracking jokes all day and seeming invincible, that nobody has any idea that we’re suffering.

I forgot to share with you a letter that I got from, from Sherry about Steven Ortiz, just to show you what a fun, great guy he is and how he kept smiling and was happy until the end. Nobody had any idea.

Dear Pamela, I’m the nurse who received the goodbye message from Dr. Steven Ortiz. I rushed to the hospital to see him and the police were already there. I still think of him all the time. He is such a sweet man and a great orthopedic surgeon who really cared about his patients and all the staff. One of the stories about him that stands out to me is he had to cancel a patient because the hospital did not secure an assistant for the case. She had been given Versed to calm her anxiety and couldn’t drive. He held her hand and explained the situation to her. He then decided to drive her home in her car over an hour from the hospital and took a cab all the way back to the hospital. He spoke to me several times about his struggles with work and his personal struggles. He called me the annoying little sister he never had because we would goof off and pick at each other on our OR days. Oh, and one time we were talking about a brewery and doing the VIP area. He was very popular with the ladies and we joked about hosting a date Dr. Ortiz event there. He laughed. The Friday before his death, he came out with a bunch of us and stayed for a longer time than usual. When he left, he hugged tighter and longer than he ever had before. ~ Sherry.

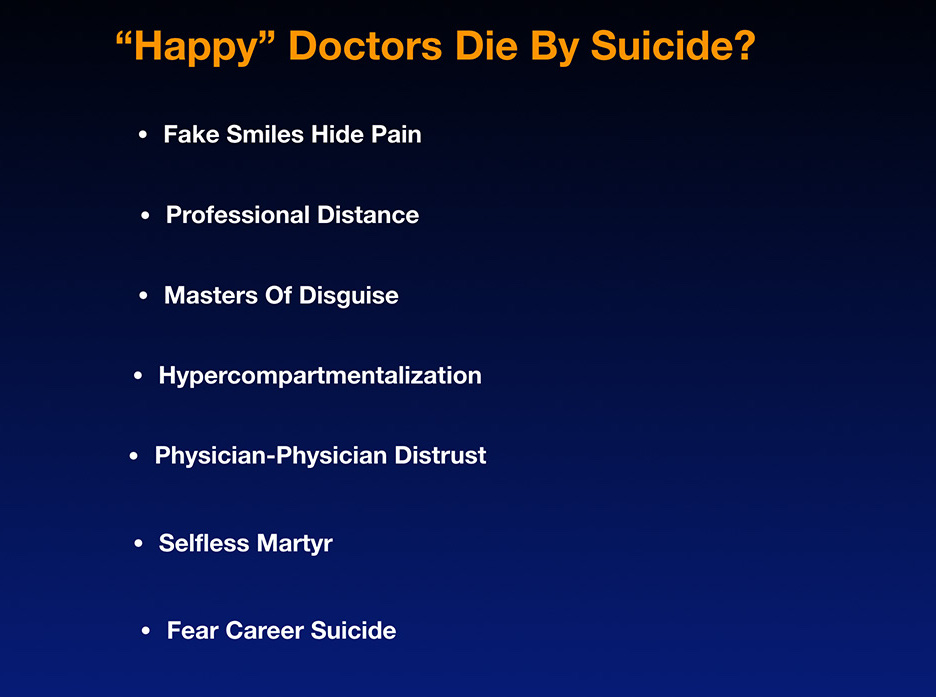

There we go. That’s all the indication he gave. So why happy doctors die by suicide. I have a little list here that might help us. Fake smiles, hide their pain. We’re trained in professional distance, so we’re not supposed to let anyone know we have any feelings at all. We’re masters of disguise. That’s part of the professionalism thing we have to follow. And as a result, we become hyper-compartmentalized, which means we play really hard and then we work really hard and we work really hard and then we do vacation here and then we … like everything is in the compartment. So basically what happens … oh, and by the way, something I found really interesting is like physicians, by nature, distrust each other. Like there’s a lot of physician physician distrust. Oh, and then we’re like the selfless martyr. And we also fear career suicide if we let anyone know.

I mean, this compilation of things leads people to be smiling and joking all day like they don’t have a problem in the world except that they’re planning their suicide and going home and getting a rope. So here’s what suicidal doctors look like. They look like these three guys. I bet there’s a lot of suicidal doctors walking around today in the US and around the world that all look like this. But the next picture you’ll see is me—this is really what they look like, but doctors don’t show you what they really look like. And I’m hoping that we’ll start showing everyone.

As physicians, my call to action, please reveal your feelings and let people know that you’re hurting and crying because hurting and crying by yourself and feeling hopeless is not a recipe for success. Just like hiding your diabetes and your hemoglobin A1C under your pillow won’t help you either. We sort of have to let people know what’s going on.

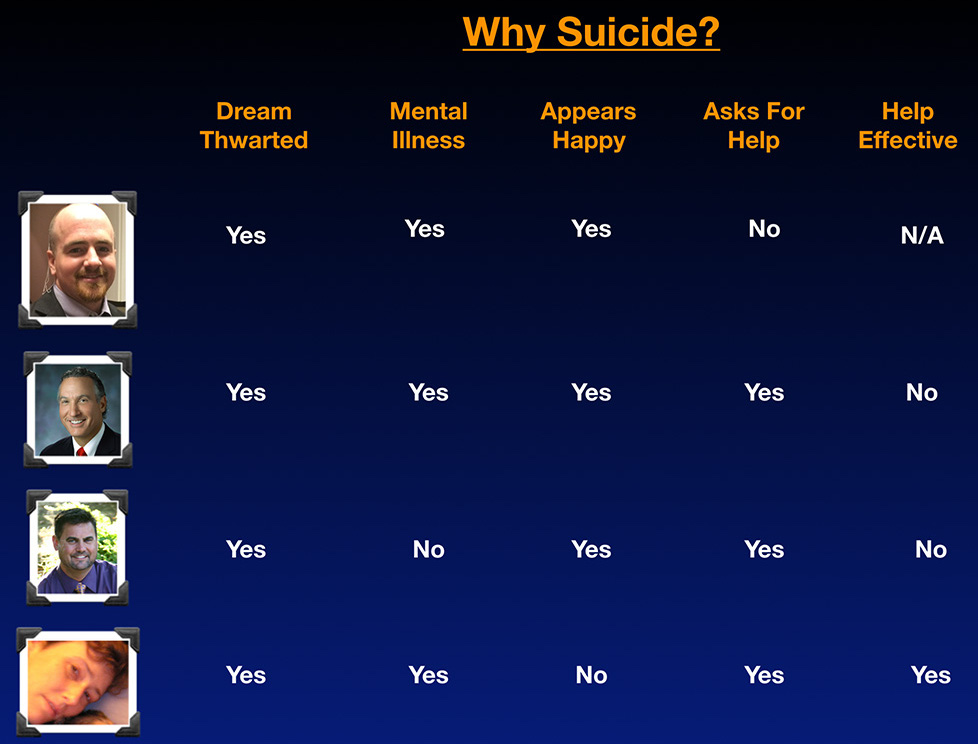

The next slide is super interesting because I decided to figure out why this was happening by just comparing the four cases.

Now, the first issue we have is your dream has been thwarted, generally. Yes. It has been thwarted because he had academic issues with Matt. Yes, the dream was thwarted for Ben because he just couldn’t keep working. He was so frazzled by his anxiety and the medication he was on and his insomnia. Yes, Steve’s dream was thwarted because he couldn’t deal with some of the things he considered fraud going on at the hospital and stuff that was happening. And yes, I was suicidal because my dream was thwarted and I didn’t like being an assembly line worker.

So that’s one thing you could think about. Is your dream being thwarted? Is the thing that you feel like you’re living for, that you’ve wanted to do ever since you were 13 or three years old or whatever, is something getting in the way of you doing that? Because if so, I think you’re at risk, especially in medicine where our identity is so wrapped up with our profession. I think you’re at risk of dying by suicide or being very sad, at least.

Is mental illness an issue? Yes, with all of us except for Steve. Steve’s suicide was not mental illness related. He made a logical choice based on his work situation. He felt like that was logical and rational to him.

Always appears happy. Yes. Everyone always appears happy except me. Here I am. During the six weeks that I was suicidal those near me knew I wasn’t happy, but that’s because I was moping in bed and I didn’t get up for six weeks. It’s pretty clear.

Asks for help? Well, Matt didn’t ask for help, but everyone else did, which is interesting. This was a group that did ask for help, meaning Ben was seeing a psychiatrist, but the meds they placed him on, obviously were not helpful because that’s what spiraled him down the tubes. Steve sort of asked for help. I’ve talked to a number of doctors who worked with Steve and he did let them know he was really disturbed about the way things were going and they didn’t seem to have an answer. Actually, they told him, “Well, just go with the flow. This is the best it’s going to get. This is just how it works here. You just have to suck it up and do it.” Well that didn’t really work for him. I asked for help, but I did a sort of interesting thing. I’ll share how I asked for help.

So was the help effective? Well, with Matt, if you don’t ask for help, your help is not going to be effective because you’re not going to get it. With Ben, no. The psychiatrist, the meds he was on, did not help him and made him worse. And with Steve, saying, “Just go with the flow. This is as good as it’s gonna get,” didn’t help. For me, the help helped. Now, how did that help? I’ll share how it helped. Here’s my suicide survival story.

I asked for help and I asked for help from the right people. Even in my suicidal depressed state, actually, I was starting to ask for help before I became suicidal and I was just seriously depressed. But I made this decision not to ask other medical professionals for help because both my parents were physicians and I’d ask them for help and they were not helpful. My mom actually sent me psych drugs in the mail during med school, just sent me Trazodone. I took it one night and then almost fell down. She said, “It might make you really tired.” I was like, “Okay.” I took it, then I went to go take the trash out in my apartment, and almost fell down the stairs. But I just took it one night.

So I just don’t feel like my parents were really helpful. I think because they’re not people that are really emotionally and spiritually accessible and I’m an extremely emotional and spiritual person. And so I felt like they didn’t even get it when I was like, hey … I mean they love me, but they just were not able to help me. And I made a decision that I wasn’t going to ask them for help again because I didn’t feel like they helped the first time. And so then I also decided I wasn’t going to go to a psychiatrist and ask for help because my mom is a psychiatrist and I thought she was sort of not really that great for me. And my mental health … sorry, earlier in my life. So I was just like, I don’t see how this is going to help. So I was thinking maybe all psychiatrists are not that helpful. This is just what I was thinking in my irrational state of trying to figure out what to do when I wanted to kill myself.

And then I was like, “Okay, let me just think about this. I’m upset because I’m trapped in assembly-line medicine and big-box clinics and I don’t think other physicians know how to get out of this because they’re all trapped there too and the patients don’t like it.” So I had this great idea. I had a vision—a prophetic dream. Why don’t I just ask the patients what they want? If I invite … oh, I had this really wild dream that woke me up out of my suicide. I feel like it was a message from God. When I describe this to people who are like Catholic or different religions, they’re like, “Oh wow, you had a” … and they had a word for it, I forgot what the word is.

But I think people pay like $30,000 to sit with monks in caves in other countries try to get these prophetic visions to happen. But me, I just laid in my bed and as long as you’re still breathing, it’s possible that God might speak to you or something can happen where your life can be saved. But in the nick of time, it was 6:00 am, December 7th, 2004. I had just slept through my 36th birthday two days before and I woke up all of a sudden with a vision of everyone coming together and me designing healthcare and patients and everyone holding hands, police officers, firefighters. I saw like a happily-ever-after story where everyone built their own clinics and hospitals and I just got really seduced by it and I was like, “Well, this is better than just laying in bed in a stupor. Oh my God.” So I called the newspaper and said I was going to lead a town hall meeting and invite the whole county, I guess this is bipolar . . .

I went from like not moving for six weeks in a coma. Seriously depressed and suicidal. To leading nine town hall meetings in my community. It’s all how you channel your mental illness. And I invited people to design their ideal medical clinic. I was like, “Hey” … I just told people in my town, “I’m suicidal. I can’t be a doctor like this. I hate working in seven minute increments. You probably hate it too. Let’s do something different. Now, you tell me what you want, as long as it’s basically legal, I’ll do it.” And so they filled out all these sheets and I got a hundred pages of written testimony over between January 20th and March 6th of 2005. I was able to … I mean I pretty much told people like, “I’ll make all your dreams come true. Let me know what you want.” I even told them there was a medical journal following us, our progress, but I didn’t know of one that was really doing it, but in my dream, I saw it happening. So I just told them.

And you know what? Four months later, after we opened, the medical journal did the story on it. So hey, it happened. I really do feel like that was a prophetic dream. It lifted me out of the worst case of despair and suicide of my life. But I mean, I’ve never been suicidal before or after. I’ve been depressed sometimes after, usually every seven year cycles. If I am bipolar, I get depressed maybe every seven years. I mean, seven years of getting a lot accomplished and a little hibernation break every once in a while. So anyway … so what I want to say is that I read all those 100 pages of written testimony, adopted 90%, and we opened the first clinic in the entire country designed by patients. Okay? And so as a result, not only did I have my suicide cured by my patients, I ended up having an amazing life.

Here I am doing house calls and then also loving my patients. Look at Johnny, he’s so cool. I love him. And then I’ve got …

Look, I’m doing oceanside appointments on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. I love Oregon, even though there’s a lot of snow.

And then I even do quadracycle visits. Yep. I will do your medical appointment anywhere where you are. Under a tree, under a bridge, on your quadracycle.

I even do surprise birthday physicals and there’s more to that. She thought she was getting a physical. I had all her friends. She’s my friend. I had all her friends hiding in the bathroom. So she went around to get undressed and they all jumped out with balloons. And so then we all went out to dinner together and we had to reschedule her physical. But it was really fun because I had forgot her birthday so many years and she’s a close friend of mine that I just decided to do it this way. “Oh, it’s your birthday. You should come get a physical.”

I want you to see these are examples of happy doctors, I think to solve the suicide problem, we could go in one of two directions. You could do what Maslow does, which is study what makes happy people so legitimately really happy, or You could study the problem and keep trying to figure out why there’s the problem. So I’m sort of working in both areas. I have all these retreats. And by the way, I have a free retreat coming up for suicidal doctors and suicidal medical students. If you ever want to come to a free retreat and hang out and leave like this, it could be better than a psych drug. You never know. But I think losing our mentors and not really having super happy doctors to be around kind of puts us in a state of despair. Just want you to know this is an option and has really helped me to be around other happy doctors.

What are the simple things we can fix now?

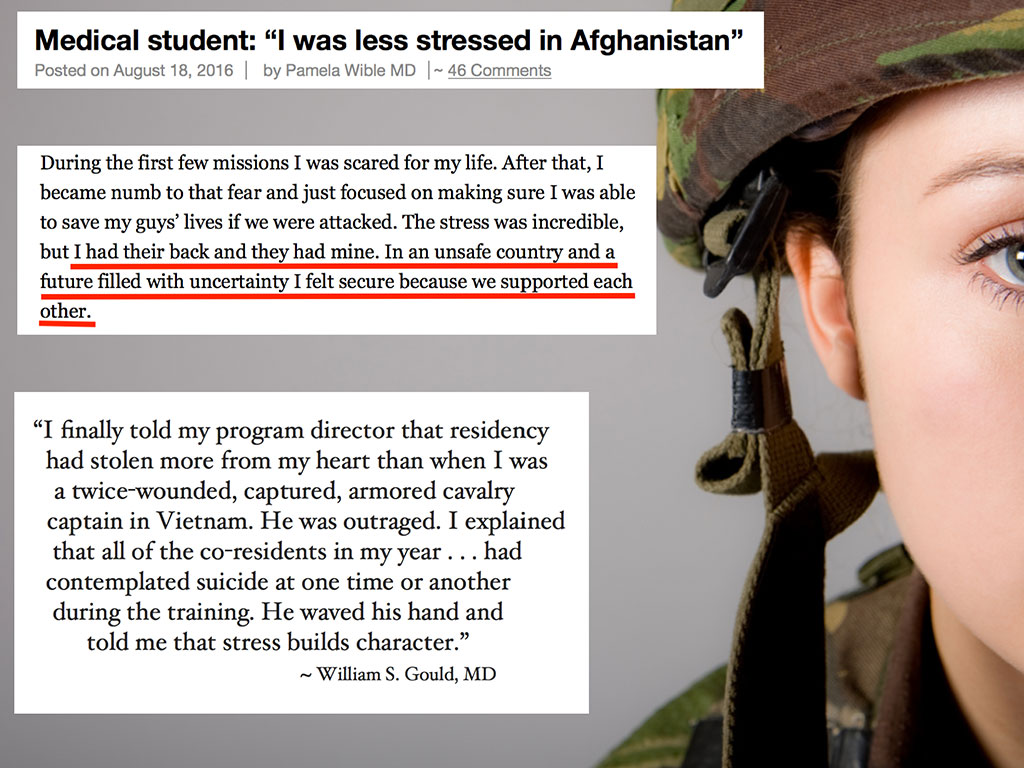

One of the things we can fix is that I got an email that really shocked me when a medical student wrote, “I was less stressed in Afghanistan.”

This just was shocking to me. She wrote, “During the first few missions, I was scared for my life. After that, I became numb to the fear and just focused on making sure I was able to save my guys’ lives if we were attacked. The stress was incredible, but I had their back and they had mine. In an unsafe country and a future filled with uncertainty, I felt secure because we supported each other.”

That’s the key, not just lip service, we’re a team, but like you know that they have your back and they’ll be there for you. Like even if you got blown up by a land mine, they would pick your body parts up and put you in a body bag and be covered with the American flag and you’d go back home, yet in medicine we don’t have this feeling that the person next to us has our back and is going to be at our funeral and love us to the last breath on this planet. Now in the military, they have that and you sort of know who the enemies are and who’s on your team. In medicine, you don’t know who the enemies—could be your attending or chief resident. You don’t know who’s going to scream at you next.

What a terrible situation for sensitive people that want to learn that are Valedictorians. I mean, the thing is we’re picked because we’re the cream of the crop. So we shouldn’t have to be terrorized to learn. We should be in a safe learning environment where we can really thrive and feel like we’re in a family. This is another quote that I saw from a guy. Similar sentiment of feeling safer in the military than medicine. “I finally told my program director that residency gets stolen more from my heart than when I was twice wounded, captured armored calvary captain in Vietnam. He was outraged. I explained that all of the co-residents in my year had contemplated suicide at one time or another during the training. He waved his hand and told me stress builds character.”

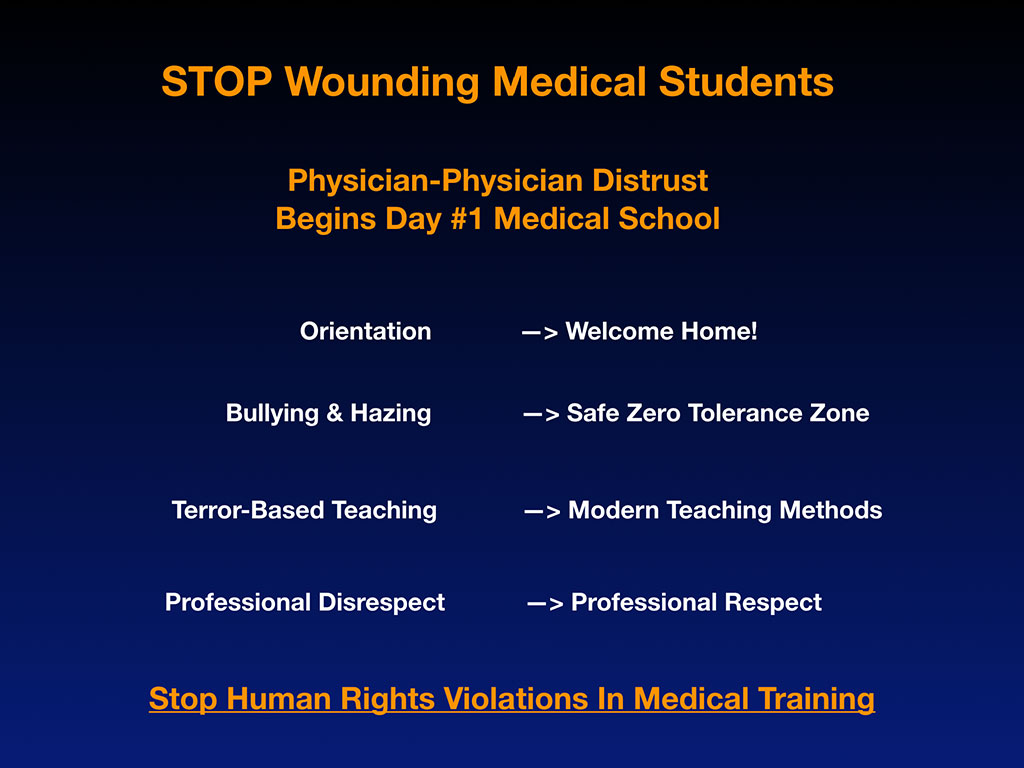

My first suggestion is that we stop wounding medical students. Physician-physician distrust begins on day one of medical school. In orientation, sometimes they still lead orientations like, “Look around the room, half of you won’t be here next year. Get studying.” Some professors during orientation have given instructions for suicide. If you can’t make it, hey, here’s how you do it. Don’t become a burden to society. Here’s how you end your life. Instead of that, what I would suggest is that you welcome people home to the family. This should be a tight-knit family like the military. We’re in it together. Right? Also bullying and hazing is just standard practice with pimping and all this stuff in medicine. Grilling people to the point of breaking them down and crying in front of the nurse’s station and the patients. We should have a safe zero tolerance zone for bullying and hazing in medicine. There’s no reason to terrorize people who already have a 4.0 GPA and want to learn. If you already want to learn, we should help you learn. You don’t need to be scared. Terror-based teaching is not a modern teaching method.

Some of this probably came from, what’s his name? William Halsted, the cocaine-addicted surgeon that started residency programs. You really can’t work at cocaine speed right now. And we shouldn’t be bullying people to do like 13 brain surgeries in 24 hours. Just move at a normal pace, eat dinner. Professional disrespect should be replaced with professional respect. I call all of this human rights violations in medical training because we are having our human rights violated in ways that break the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. And it’s not just one instance, it’s seven plus years (If you make it through med school and at least three years of residency) in which you are at risk of having your human rights violated.

We must revamp medical education and there are simple things we can do that are literally no cost and you’ll get better students. There willl be happier with higher test scores when they love each other and feel safe. There’s no reason to control people with the divide-and-conquer fear tactics that are being used now.

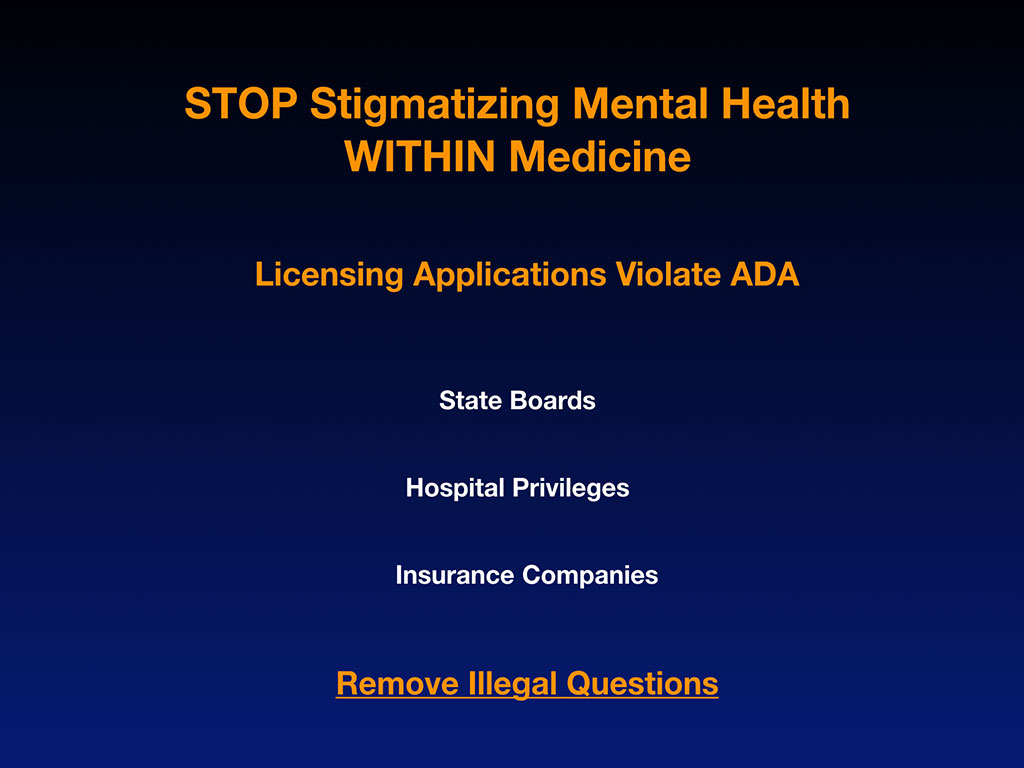

The other thing I want to share is why doctors don’t seek mental health care. And this is because we have antiquated the licensing applications that are in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. This is actually a real application I pulled this down from the Alaska … I mean I was going to look at all of them. I started with Alaska. I tried to go alphabetical. I only made it to Colorado because it’s a lot of work to review all these applications. But this would be a good project for a medical student or resident looking for a fun psych project, pull down all the state licensing applications, review their mental health questions, and do a little paper on that. You’ll probably get it published and be a leader in changing this because this should be illegal.

Whose right is it to know all this stuff anyway? If you are not impaired. Mental health issues do not equal impairment. If you are not drunk at work and you’re treating your patients great, you’re the brightest guy in the ICU, why should you be asked all these questions if you had a panic attack or you were depressed during your divorce, you know what I mean?

We should be getting help and not penalized. This is what prevents physicians from going and getting help. They’re afraid of having to check one of these boxes. And so what I’m suggesting is that we stop, within medicine, stigmatizing mental health care and that we make these questions illegal on all applications. And right now, they’re on state board applications in a lot of states. I mean, New York state, by the way, took it off completely. There is no mental health question in New York state’s application. I would recommend if you care about this and you’re in Florida, that you yank that question off your state licensing application. Maybe you could replace it with something about impairment. Are you safe to treat patients? Are you impaired in any way? Then it’s a subjective thing and the person can answer and they don’t feel violated by the ADA.

Also insurance companies, just to be on the in-network panel of Blue Cross Blue Shield, you’re having a check these questions again. Why should Blue Cross Blue Shield have access to my psych records, you know what I mean? We’ve got to remove these illegal questions. A few more slides and then we’ll go onto the panel discussion.

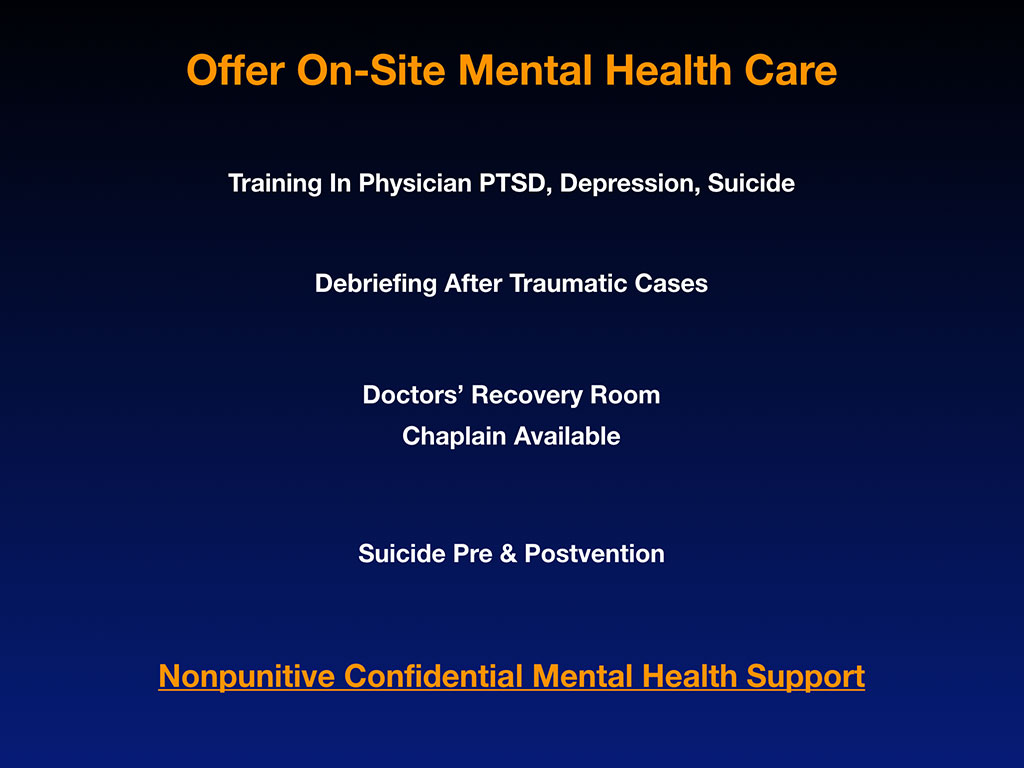

I do feel like we need on-site mental health care in medicine. Because let’s just face it, when you see even one stillborn or toddler shot in the head or something like that, that could cause PTSD. And physicians, we’re in high risk environments for PTSD.

This isn’t like baking cakes. We’re watching people die and we’re surrounded by humans suffering all day long. And so this is like the equivalent of dental health, eating Halloween candy every day and never flossing or brushing. All right? Mental Health. Rhymes. Dental health, mental health. There’s a section in the drug store for all the dental health products. What are you personally doing as a mental health flossing and brushing routine? Anything? I don’t know. Most people aren’t doing any of that. And in medicine, you’re in a high risk environment where you’re saturating your teeth with the equivalent of Halloween candy every day, right? So we have to be in some sort of a mental health maintenance program.

We do more to maintain our car, getting it’s checkups with oil changes, than we do for our own mental health. That’s weird. I’m just letting you know. I think we should address that. And we should debrief after traumatic cases. If you’ve just lost a newborn or you’ve just had a young woman, maternal death during pregnancy. I mean, you think he can just go to the next room and deliver another baby and not keep having horrifying thoughts about what happened in the other room?

We also need a doctor’s recovery room. None of this stuff is like recreating the wheel, really. We already have recovery rooms in hospitals for after surgery. Empty out a broom closet, put in a little couch, lava lamp, little refrigerator so you don’t have to steal the crackers and apple juice from the patients in case you’re hungry. Maybe real snacks like Power Bars or something. Put an affirmation on the wall, a lavender spritzer. Just make a cute little kind of relaxing room so that in case you, God forbid, have a maternal death, you don’t have to hide in stairwells. Right now doctors are going into bathroom stalls, hallways, and sneaking out into their cars in the parking lot and crying so nobody sees them. But see, this way you could go into a room (and the nurses in the ER need this too) and cry without crying in front of the patients or having a breakdown in front of everyone.

You just saw something scary and terrible. You were involved in it. You were the last person there to say that the baby’s coming out and now the baby’s dead and now the mother’s dead. This is traumatic and we need to be able to press the chaplain button. The chaplain already works in the hospital, so why not press the chaplain button for help and they can come help you because you might need help too. Not just the family who lost the mother and the child. Suicide pre- and post-vention. This is all part of preventing suicides. Part of those 100 lost opportunities with these people.

Post-vention just means after a suicide that we actually talk about it because if we censor it, it sends the message that, “Oh, it’s not okay to die by suicide or talk about suicide.” And I have to keep pretending and smiling every day. And so this is the message that’s been going on since 1858, and I think it’s time to change it. So non-punitive, confidential mental health care is key.

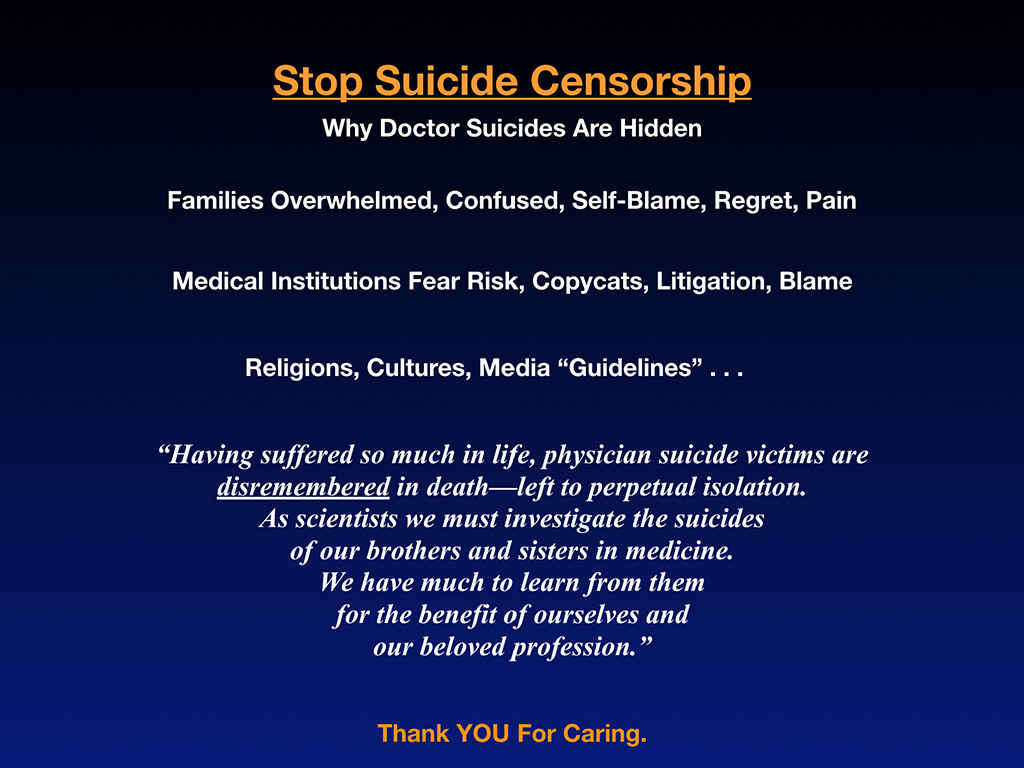

My final suggestion is that we stop suicide censorship. These are why doctor suicides are hidden. Families are completely overwhelmed, confused. They sometimes blame themselves. They get stuck in regret and pain and keep thinking, how could we have done this differently? Families are in no position to take like a leadership role in changing the whole doctor suicide crisis because they can barely cope with the fact that they lost their child.

Medical institutions fear risk and copycats and litigation and blame. And so they don’t want anyone to know.three doctors jumped off the rooftop of their hospital in the last two years. But if you don’t tell anyone and your solution is just to put a chain link fence up and bolt the windows down, then you just have suicidal doctors that are bolted in. They can get out somewhere and they still have access in the anesthesia room to the drugs. And if you Google “doctor found dead in hospital,” they’re pretty much all male anesthesiologists and they’re all overdosing INSIDE hospitals.

We’ve got deal with this. And with these doctor suicides inside hospitals they’ll report “no foul play.” And I’m like, “No foul play?” Are you kidding? This is happening at every hospital in the country. There’s dead doctors. I mean, there is something at play and it’s foul when so many doctors are found dead inside hospitals. Not to do something about this? It seems foul play to me not to intervene.

Religion, cultures, media guidelines, continue to censor. And so my final remark is having suffered so much in life, physician suicide victims are disremembered in death, left to perpetual isolation. And if I were not here flying through the snowstorms to do this, these people who I talk about, Ben Shaffer, Matt Wittman and Steven Ortiz could be at risk of being left to perpetual isolation in death. Which is what killed them in life, sort of. They were isolated and felt hopeless. So as scientists we must investigate the suicides of our brothers and sisters in medicine. We have so much to learn from them for the benefit of ourselves and our beloved profession. Thank you for caring.

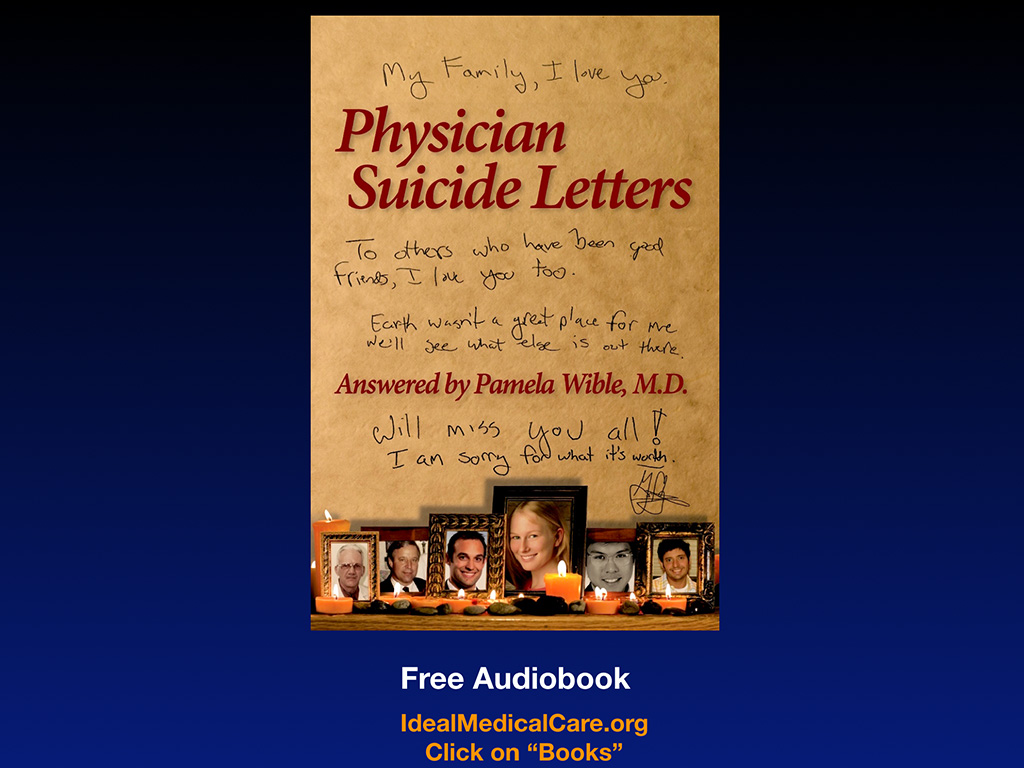

I’m going to take questions in a minute. I want to draw your attention to a free book that I have online —published suicide letters from doctors. I know it sounds super depressing, but it’s really inspiring. Only a few of the people are actually deceased. This is like a print version of the suicide hotline that I run with physicians. So this will give you like a really deep perspective on why physicians and medical students are suffering and there’s lots of solutions offered in the book.

Finally, I want to honor the three people that I remembered through my talk and take a moment of silence with everyone to just look at this slide as we get our panel together. And we’re going to play a song here in a minute too during this transition. Just look in their eyes. Look at them. There’s a lot of doctors like them right now.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Dr. Pamela Wible: Here’s our esteemed panel. Our first guest is Clay Wittman. He’s a personal friend and a lovely gentlemen. A member of the FSU College of Medicine family now, for a lifetime. He works tirelessly alongside many passionate people to help students in need and honor the memory of his beautiful son Matt, who would’ve graduated this May with the class of 2019. Clay and his wife Julie live in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where Clay is the principle of Wittman Legal, addressing criminal defense, estate planning and general civil matters. After 26 years in the US Air Force, he retired as a colonel in 2009. In addition to his own practice, he volunteers, like his son, with the homeless. He has a homeless veterans legal assistance clinic and he has expertise in helping the Kent County Veterans Treatment Court. So definitely his heart’s in the right place, like his son. We knew that, and so let’s hear it for Clay.

Our second panelist truly needs little introduction as she is a trailblazer in the medical community here. She’s the past president of the Volusia County Medical Society. Doctor Delicia Haynes started the very first direct primary care practice in the area and is celebrating her 10-year anniversary as the owner, the founder and CEO of Family First Health Center this month. Let’s hear it for that. Delicia is also releasing her new book, The Dawn: a Med Students Roadmap to Finding a Light in Their Darkest Hour. That’s a personal reflection of her own struggles as a medical student, which she’ll share with us. I’ve known Delicia for at least 10 years since I saw her bright shining face on the cover of the American Medical Association Newspaper and consider her to be an amazing physician, a great friend, and a leader of the next generation of physicians.

And I’d like to welcome our final guest, Sherry Cleveland, an RN, who drove in from Spring Hill, Florida without any snow problems today to be part of our event. Sherry began her career in the legal arena as an administrator in the county court system. She made the move to healthcare seven years ago and was very fortunate to be able to work side by side with such a wonderful man and spine surgeon, Dr. Steven Ortiz, She is here tonight to share her story and to continue our collective healing. Let’s hear it for Sherry.

So we will now take questions. If anything I shared provoked any thoughts or anything that you would like to ask.

Clay Wittman: Dr. Pam, I would like to interject a little bit. She mentioned that she fought off a snowstorm with a broom and rake. I’m from Grand Rapids, Michigan. When I went to airport at 6:00am, there was 51 degree temperature differential between here and Grand Rapids. It was 15 degrees when I left. So we have a lot of snow shovels we’d be glad to send her in Oregon.

Woman (Audience): I think you wonderful people should just move to Florida and you wouldn’t have to worry about any of that.

Clay Wittman: Another thing I would like to point out is I am, as a non-medical person on this panel, I’m honored and humbled to be here. And more so with my 26 years in Air Force, I’m especially humbled to be in the presence of a medical doctor who’s here in this room. It was a long-term prisoner in Vietnam. I heard his story tonight and I was deeply humbled and I’m honored to be here with him. I also want to thank, and I’m gonna get emotional, I try not to do this, but I want to thank Dr. Dunn here at local Campus for his warmth and taking care of me and my trip. Our discussions going back, we’re both Air Force Academy graduates, although he was quite a few years before me. And we had a great discussion this afternoon, so thank you for your time.

Dr. Pamela Wible: So we have handheld mics moving around for people who have questions. Just raise your hand, I would guess.

Male (Audience): Dr. Wible, thank you very much for the wonderful, wonderful presentation. I graduated medical school in 1992. To hear your testimony and tell the story of each gentleman was inspiring because I think we all go through low points in our lives during her medical training and in our careers. I think I’m still trying to figure out if I went into the right profession or not. It took me 50 years to figure this out, but I’m happy with my decision. But it was always a struggle right up until the recent past. I got to wonder though, since the years I graduated, you described you know personally 10 people that have died by suicide in medical school or in their profession. I know zero. I wonder if in your statistics, is there a regional bias? Does it happen more in certain parts of the country or is it just a general phenomenon that we see across the country? I will also admit that I don’t really keep up with my friends very well, so it might have happened. I don’t know about it. But it just seems like it’s a tremendous number that you’re contending with there.

Dr. Pamela Wible: What’s your specialty?

Male (Audience): I’m an interventional radiologist. That was way down on the list.

Dr. Pamela Wible: I think there are some people less scathed by the medical education system and obviously there’s more progressive schools than others. It’s such a combination of factors like your innate real resilience. I think by the way, we are a very resilient crowd in general, and I don’t know that we need like a lot more resilience training if we’re already working 100 hours a week. What we need is access to mental health care. Some people who are less likely to die by suicide. Certainly some specialties are lower on the list. And I think that if you’re a male, linear thinker, medical school comes easier to you, that is a protective. Me, I am super creative, emotional, not a linear thinker, so medical school is this huge challenge for me and it just. I ended up studying so many hours, so ineffectively.

Also has to do with your support system. I think people who are married during medical school or have like a church, or have family nearby (who didn’t pressure them into medical school). So there’s a whole issue of people being pressured to go into this profession. So if you’re in the wrong profession, like truly you hate medicine and you don’t like people, this could be really traumatic. There are people like that who call me up that are pre-med and say, “My family thinks I should go to medical school because we’re all radiologists in my family, but I hate people and I don’t like math or science. What should I do?” Don’t go into medicine. Okay. So do you have a support system? Are you in a high or low-risk specialty. Is the way your brain works set up to optimally function in medicine?

It’s just sort of hit or miss. Who gets the malignant attending on that wrong rotation that just kind of picks you as their special pet project to slaughter. And you never get over that bullying, you carry it with you the rest of your life. And it’s also the traumatic cases you’ve had. Like I’ve never had a maternal death. Every so often I do hear from a man who says, “I don’t know anyone who’s died by suicide on medicine.” And congratulations! You must’ve done something right or been in the right med school or residency or …

By the way, I loved my residency program. Absolutely loved it. So I don’t have … Some people claim, “Oh, she can’t stop talking about suicide. She really hates medicine and hates her education.” No, I had a great three years in residency. So other questions?

Dr. Delicia Haynes: I think the point that she was making also about one, we don’t talk about it and we don’t know if it’s not classified as a suicide. We’ve lost physicians in our community. We’ve lost dentists in our community. And I think it’s more so that no one really talks about how they died or what happened. And it kind of these whispers that happen. So I think that we all know more people than we realize. When I started talking openly about struggling with depression myself, now I have all these patients who are telling me about their struggle with depression. But before I let it be known that this is something that’s okay for you to have, to emote, you’re seen as this superstar in your community and all this. And not that that’s not true, but that you still struggle. And so I think that we don’t ask the question and we don’t really know what’s going on with people. Because we all look fantastic on the outside. Professionally, we know how to put on the mask. And so even if you you were right next to us, you don’t even know what we’re struggling with.

Dr. Pamela Wible: And along the same lines, I’ve spoken to some doctors that are retired in my town and when I speak to them, they’re like, “Wait, do you have this guy on your list? And what about this guy and this guy?” And so I have like 14 from my town now dating back to the 1960s. And it’s just a matter of having the conversation. And when I first had this conversation, I was trying to figure out what happened with this one orthopedic surgeon in my town from ’96. I started asking this retired orthopedist. Next day he called me back. He said, “You know what, Pamela.” I sat last night and really started thinking about this. I’ve got six more names to share with you.” So I think if you talk to some retired doctors, people been in the field 50-plus years, there’s more. Because nobody’s asked you to start counting the names of suspicious deaths slash suicides, most people have sort of a “suicide amnesia.” Who wants to remember these traumas. We try to forget them.

Female (Audeince): Hi Dr. Wible, thank you. And I thank everyone on the panel as well. Thank you all for everything you share. While you were speaking, it was making me think I wasn’t the only one but just with the pressures that different people with different types of experiences. And it was making me curious. I know medicine is now becoming more diverse. We have a lot more minority groups coming into the field and I know just being minority, that carries along with it its own stresses. So I was wondering how, if that has affected the numbers in any ways throughout the years, and if you have any suggestions or recommendations with that as well.

Dr. Pamela Wible: Yes, absolutely. I think the history of medicine is sort of a patriarchal reductionist medical model. So when you have these holistic-minded, younger, darker-skinned women and J-1 visas coming over, there is certainly tension between the old guard and new guard. Put it that way. And this definitely came to the surface for me when I was counting the number of suicides at Mt. Sinai in New York City and there were three women within two years. Two of them were J-1 visas from the nation of Mauritius and they both stepped off the roof of the same building. And so that’s when you’re looking at these numbers and you see, okay, in Florida it’s 98% male, right? But now how did we get three females from one institution in New York? That seems like an outlier.

I noticed the outlier emails. Losing eight colleagues in anesthesia, Ding, Ding, Ding, ding. Maybe anesthesia is a problem. Or three women at one institution, two from one nation, right? So I think it is more stressful for women. More stressful J-1 visas. Definitely there’s more tension. If something were to go wrong, you’re getting deported back to your family, who will feel shame, “What happened to you? Couldn’t you make it work?” Sort of thing. There’s two Muslim women within a few weeks of each other that died by suicide. I became very close to those cases.

Also there’s this phenomenon that goes on in Indian culture where several times I’ve heard from a pre-med or a med student who says, “I’m in medicine because my grandfather knew I would be a doctor and my mother had a dream that I would be a doctor. And so now I’m in medical school.” Well, just because your family had a dream or planned at your birth that this is what you should do is not necessarily the right profession for you. So I think there’s Indian, some East Asian cultures, pressure. Also, I get really suspicious when there’s a family where everyone’s a radiologist and then this one died. Or everyone was a trauma surgeon and then … It’s like, I don’t know, everyone trying to match in families—being circumcised with the first name starting with the same letter and everyone has to pursue the same profession. That doesn’t always work out. Some people, their souls are meant to go in different directions than their family members. So any other questions?

Female (Audience): Do you actually go to medical schools and give a program to prepare students for this?

Dr. Pamela Wible: Do I ever go to medical schools and give a program to prepare them for this? Well, I think the best time to prepare for this is before you get into medical school. I’m happy to speak anywhere, by the way. A few days ago I was in Pittsburgh speaking to 400 pre-health students. So they were getting ready to go into like dentistry, veterinary medicine, med school and all that. And that’s the perfect time for them to understand mental health risks for various professions. And by the way, veterinarians are very high too. They’re just like anesthesiologists, with easy access. That’s what they do all day—euthanize pets and see the end result of human psychology on pets. And nobody wants to pay for pets and they’re making lower wage and seeing terrible misery. You know what I mean? And so I think people deserve to know before they enter a profession what’s going on. And then once you’re there, of course, the medical school should be set up in a way where it’s really kind of a family atmosphere.

So to answer your question, I’m totally available to go anywhere including, I’ve led candlelight vigils and memorials for a J-1 visa victim at Mount Sinai because otherwise there was like no public funeral for her. And then you leave the colleagues. I just want to point out in her case, I know this isn’t your question, but this is called the need for post-vention after a suicide. When you step off the building in New York City in the middle of the day at 3:30 as a private Muslim woman who could have overdosed in an apartment, that is a real statement suicide. And a number of people have just seen you do this and now you’re on the ground covered in a tarp.

One resident contacted me and she said she was doing a procedure on a patient and she looked out the window and saw the whole thing happen. She couldn’t stop the procedure because she was like involved inside of a patient’s body with the procedure. Meanwhile she’s crying and having flashbacks to the three other doctor suicide she experienced since graduating medical school over the last five years. So what happens if you don’t deal with these suicides right away and allow the surviving classmates and colleagues to grieve? They’re set up for having these flashbacks their whole life and just other perverse ways that they deal with their mental health because they go into hiding even further because they don’t feel safe. So that’s why grieving should really happen in a community.

Look at what happens after a school shooting. They bring in counselors. There are teddy bears in the fence. There’s a candlelight vigil at the church. Everyone comes together and has a community-wide grieving process. That same thing should be going on at medical schools. And I’m happy to lead them wherever they happen. I’m happy to lead eulogies and memorials. I mean, I hope that I don’t have to really do a lot of them because maybe after we start doing this, people will stop dying by isolation and hopelessness and loneliness in medicine. But yes, this needs to be part of an institutional program to combat an institutional professional occupational hazard that is unique to medicine—and so obvious by the numbers and losses that we’re suffering.