Last week I delivered this talk twice at the American Academy of Family Physicians Scientific Assembly in Washington DC, and I also presented it to third-year medical students at The Commonwealth Medical College of Pennsylvania. It is fully transcribed here. Every medical student and physician needs this information. Please share widely. You may save a life.  Dr. Wible: Welcome to Physician Suicide 101: Secrets, Lies & Solutions.

Dr. Wible: Welcome to Physician Suicide 101: Secrets, Lies & Solutions.

I’m a family physician born into a family of physicians. My parents warned me not to pursue medicine. So I went to medical school. Ten years later, I’m unhappy with the direction of my profession (and I’m not the only one). Then I get this crazy idea: what if I ask for help? Not from the profession that wounded me. Just from random people on the street. So I hold a town meeting and ask patients to help me—design an ideal medical clinic. I promise do whatever they want as long as it’s basically legal. That’s going out on a limb.

I’m a family physician born into a family of physicians. My parents warned me not to pursue medicine. So I went to medical school. Ten years later, I’m unhappy with the direction of my profession (and I’m not the only one). Then I get this crazy idea: what if I ask for help? Not from the profession that wounded me. Just from random people on the street. So I hold a town meeting and ask patients to help me—design an ideal medical clinic. I promise do whatever they want as long as it’s basically legal. That’s going out on a limb.

I’m a go-out-on-a-limb kind of doctor. In med school I protest the dog labs and I’m sent to the office of the Dean—who diagnoses me with “Bambi Syndrome.” In residency I’m caught giving patients recipes for kale salad. I’m sent to the office, reprimanded for not getting approval from the patient education committee. I’m 46 and I’m still handing out unapproved kale salad recipes—now I’m taking on physician suicide. My therapist calls me the “Dr. Kevorkian of Medical Taboos.” Before my wedding, my dad actually made my husband promise to keep me out of jail. “Always pushing the limits,” Mom says, “always going out on a limb.” Today I invite you to join me.

Here are the official learning objectives. Bottom line—I need you to take action. I don’t care what you do as long as you do something.

Why do we do what we do? To save lives. Why did you go to medical school? Seriously. Why spend your 20s studying while all your friends are at parties? To make a difference—to save lives. Why are you here? To get CME? See the Smithsonian? Rediscover your joy, your calling? What is your calling? Why are you a family doc? They recruited me for pediatrics, but I kept asking why? Why this kid’s got asthma? Why the parents smoke? Why they live next to an incinerator? I’m a family doc because I can’t stop asking WHY? So why are you here? You had 20 choices, why attend this talk? Maybe you lost a colleague to suicide, a friend in med school. Maybe you are struggling now. Maybe (like me) you just want to know why our colleagues die by suicide at twice the rate of their patients. And you want to save lives.

The fact is each year we lose over 400 doctors to suicide—that’s like an entire medical school gone. I lost both men I dated in med school to suicide. In my town, in just over a year, we lost 3 doctors to suicide. One doc in town lost 7 colleagues to suicide! (In what other profession, can you lose 7 colleagues to suicide?!) This year over 1 million Americans will lose their doctors to suicide. Why? To know why someone has died, we perform an autopsy. With suicides, we perform a psychological autopsy:

Today—for the first time—I share my results from 4 psychological autopsies:

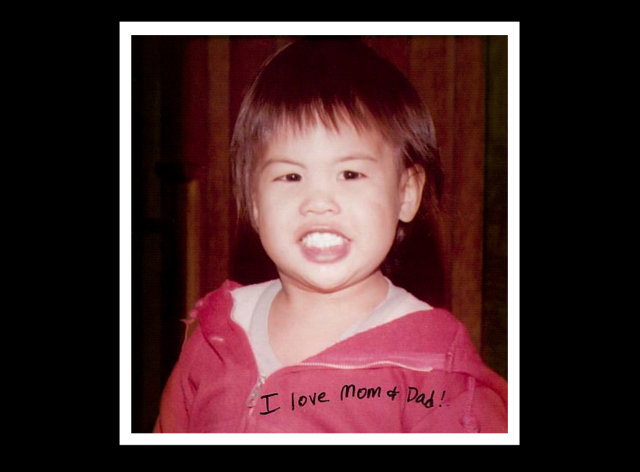

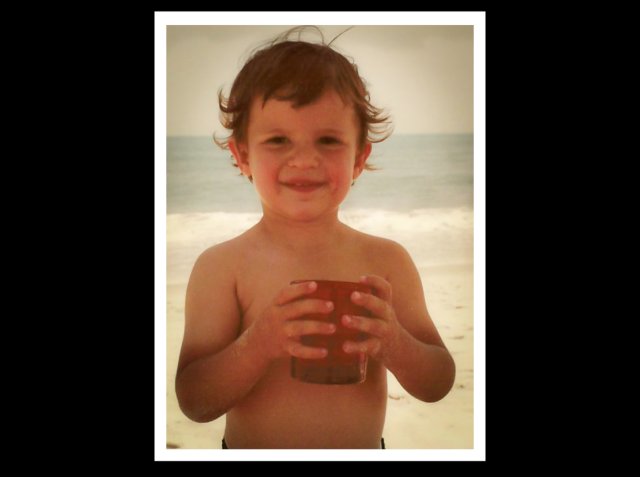

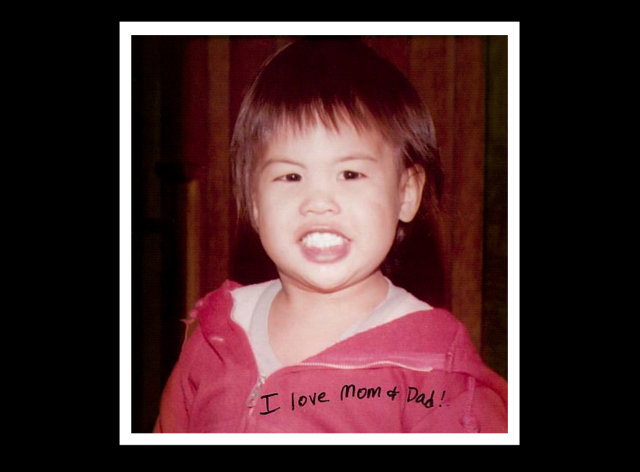

This is Vincent. He’s 2. He framed this photo to give his parents at his med school graduation. An adored first grandchild, a joyful little prankster who made everyone laugh. His Aunt Edna told me in catholic grammar school Vincent has his feet up on the chair in front of him. Sister Agnes comes by and tells him to put his feet down. He replies, “I have to keep my legs up!” She asks why. He says, “I have varicose veins.”

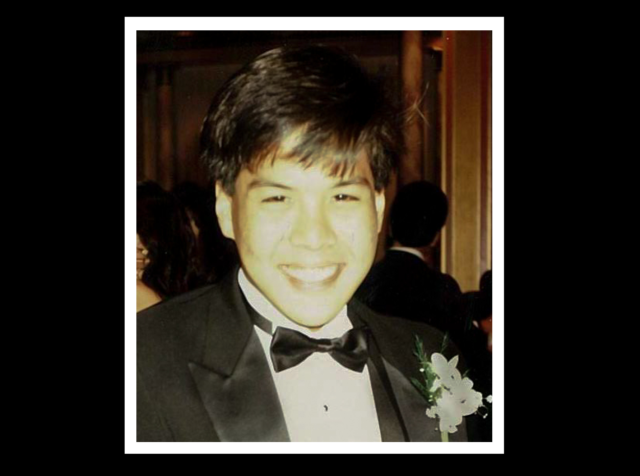

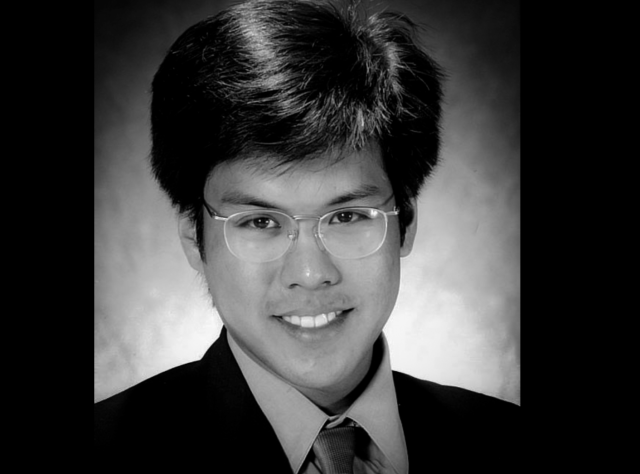

Here’s Vincent at high school prom. An athlete and artist, compassionate, sensitive, gregarious, yet private. A compulsive perfectionist. Always a good kid. Never any addictions. Just a straight forward normal good guy, according to his mom.

Here’s Vincent’s med school graduation photo—just 25 years old and 2 months after starting a prestigious surgical residency in New York City, he dies by suicide. Why? Look at his eyes. Notice the difference between his childhood photos and his medical school graduation picture. He looked happy and healthy before med school. What happened during Vincent’s medical training? I interviewed several of Vincent’s family members to find out.

His mom says he became disappointed, disillusioned. He lived near the hospital, but drove an extra 45 minutes home at every chance he had just to sleep in his own bedroom. He lost a lot of weight and his jokes and laughs were gone. His family was concerned, but they thought it was the adjustment to a demanding profession.

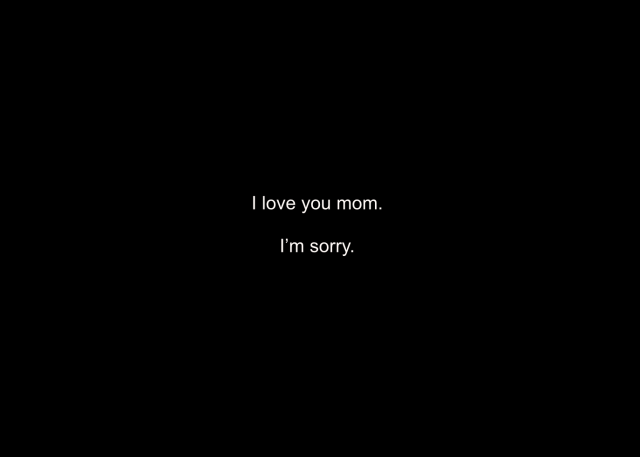

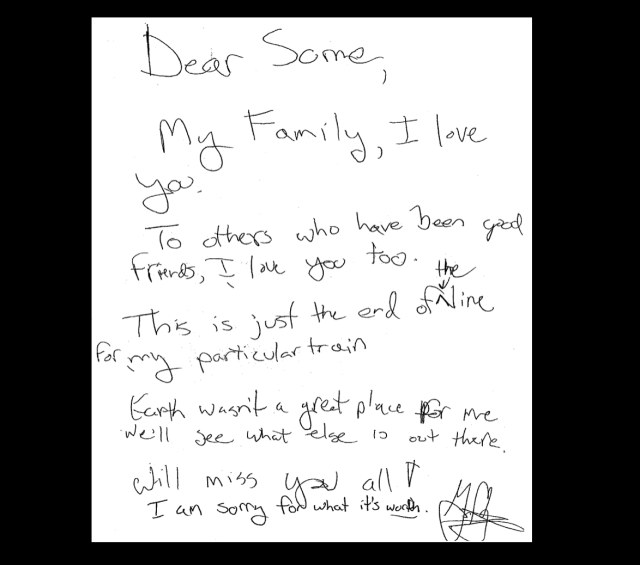

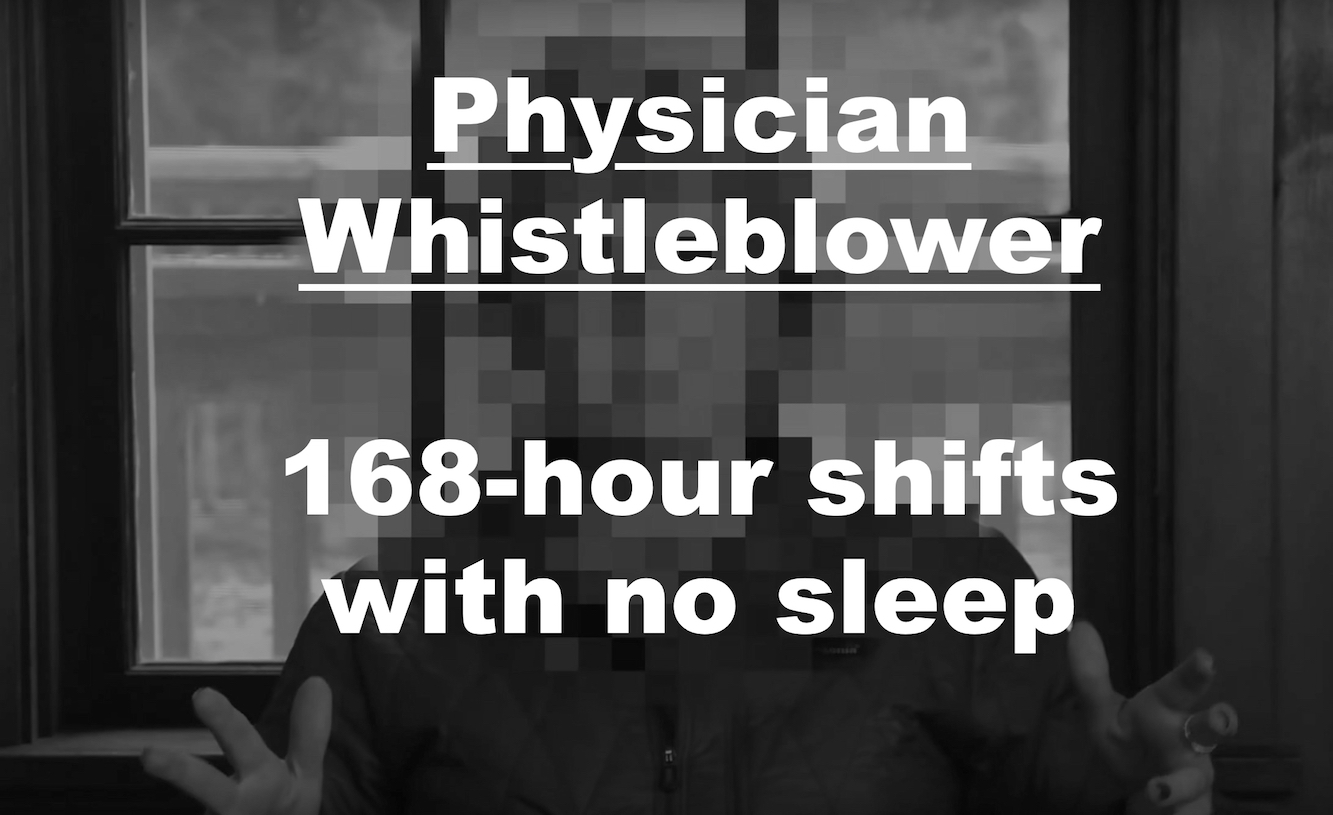

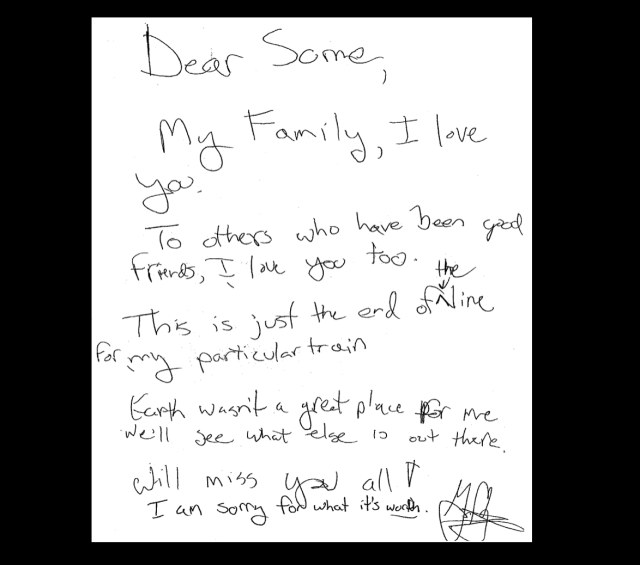

Vincent told stories of how surgeons publicly humiliated interns. How he and his partner fell asleep leaning against walls in the hospital while waiting for their patient’s turn for a scan. He spoke of his doubts about saving this one guy who jumped out of a building when caught raping a young girl who was also being treated in an adjacent room. He spoke of the sisters—victims of a car accident—brought to the ER, stunned him for a moment because they looked like his mom and aunt who often travel together without seat belts. Vincent took a belt and hung himself in his closet. The note he left:

* * *

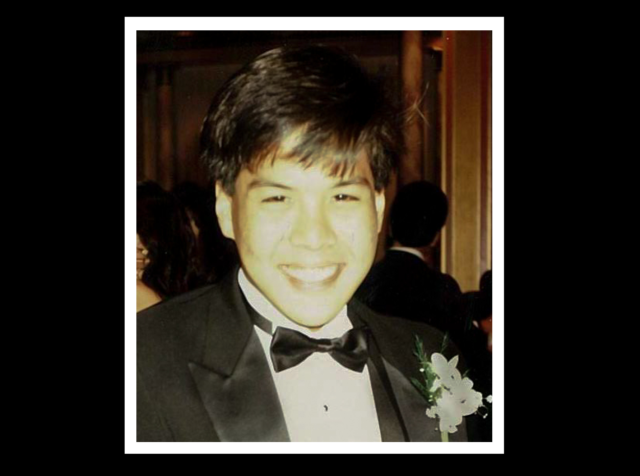

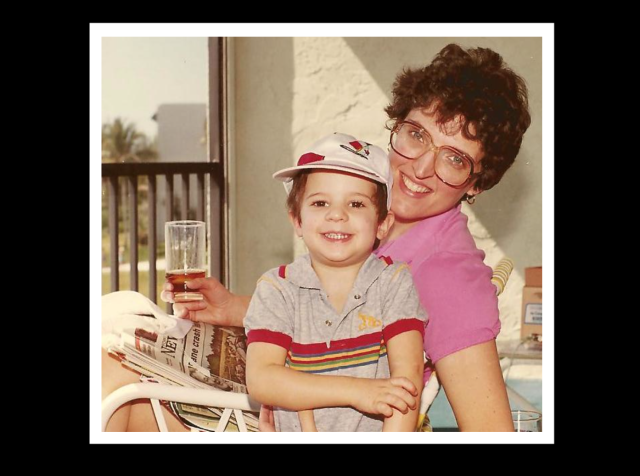

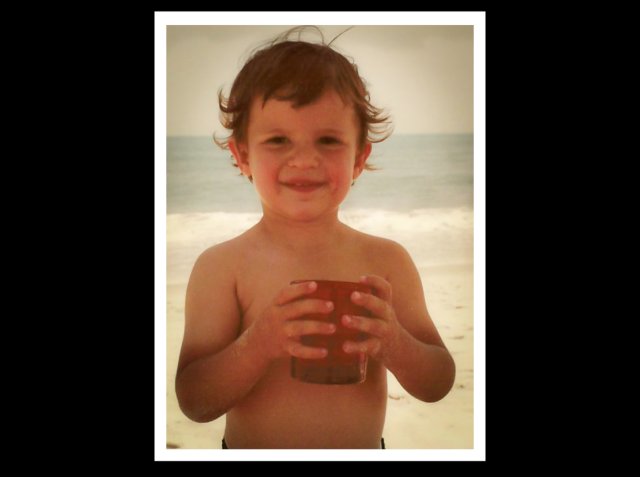

This is Greg at 3.

Outgoing, curious and clever. He always got along great with adults. At 5, he goes on this family trip to visit his great aunt—a nun at a convent. A French professor, she asks Greg to give her a word he would like to hear in French. He says, “Guacamole.”

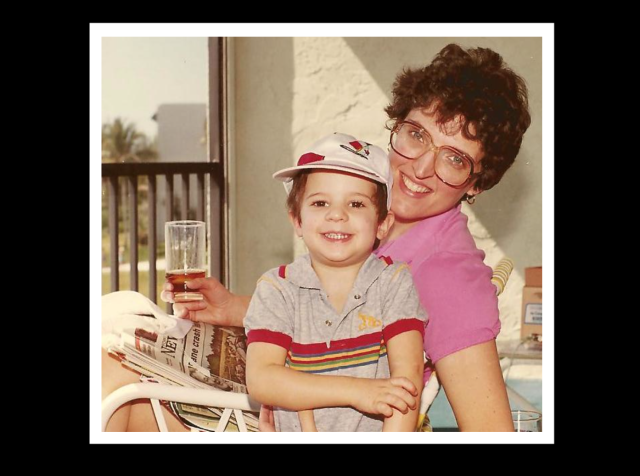

Greg as a child with his mom.

Greg graduating from med school. A pianist, painter, poet, a real Renaissance man much beloved by his patients. Greg sent this e-mail to his parents, both physicians, one year before he died

Subject: Piece of My Mind Read this if you have time. It resonated with me especially well this morning. I like these two paragraphs: I love practicing medicine. Unequivocally. Yet it sometimes seems as much a burden as a privilege. We begin our careers in the anatomy room, a ghoulish lab in which many ‘civilians’ would faint. We cut our teeth in bloody operating rooms and intensive care units from which few people leave intact. We spend our lives bearing witness to the sufferings and diseases of troubled souls. We are well paid, intellectually stimulated, and, if we are lucky, trusted and maybe even loved by our patients. Yet on certain days, when our patients do not do well, the trade-off seems untenable. How are we to protect ourselves from the emotional hazards of the practice of medicine? How are we to stand with our patients through the very worst while avoiding depression, significant stress reactions, and even substance abuse or addiction? Love, Greg

Greg was the only one in his family who struggled with anxiety, depression, and alcohol. After an outpatient program his third year of med school, he was sober until his second year of residency. A brilliant clinician, never impaired at work, but a Physicians Health Program (PHP) mandated a 90-day treatment facility 300 miles away, where Greg felt marginalized, belittled and was 3 months behind in completing residency. He felt if he were a banker or lawyer he wouldn’t have this forced upon him. He hid his depression and substance abuse and carried a lot of shame. Just 24 hours before his death (he had relapsed), he met with his psychiatrist who arranged admission at a local rehab facility. Greg notified the PHP who held the keys to his license. They disagreed with his psychiatrist’s safety plan. Greg felt humiliated, cornered, and killed himself. His mom wrote this letter to the editor of The New York Times in response to a physician suicide article last month. You may recall the article about the two young doctors—interns who jumped to their deaths in late August from their Manhattan hospitals. Greg’s mother writes:

An unacknowledged predicament for physicians who identify their struggle with substance abuse and/or depression is that they are often placed under the supervision of their State Medical Board’s Physicians Health Program. My son, Greg, was being monitored by such a program. He took his own life at age 29, one week before he was to enter an esteemed oncology fellowship. His final phone calls were to the PHP notifying them of his use of alcohol while on vacation, a disclosure he had previously described as a ‘career killer.’ These programs, which often offer no psychiatric oversight, serve as both treating and policing agencies, a serious conflict of interest. Threatened loss of licensure deters vulnerable physicians from seeking help, and may even trigger a suicidal crisis. Medical Boards have the duty to safeguard the public, but the assumption that mental illness equals medical incompetence is an archaic notion. Medical Boards must stop participating in the stigmatization of mental illness. We cannot afford to lose another physician to shame.

I read 12 pages of online condolences. This anonymous entry stands out: “Thank you for being nice to even the unpopular kids in high school. May your soul rest in eternal peace.” Greg looked out for the underdogs, but what happens when doctors are considered underdogs? Who looks out for us? Do we get the care we need? Greg didn’t. Greg transected his bilateral radial and dorsalis pedis arteries with a scalpel in the bathtub, candles lit, music playing, some wine, vodka, surrounded by family photos. Greg’s note:

* * *

This is Kaitlyn and her mom.

A sweet, good girl. Kaitlyn never gave her parents any problems, though she cried when she lost at Monopoly. From the time she started preschool, she never needed any help with her homework or anything. At 3 years old, she had to get glasses. Her parents took her to the big medical center where the doctor asked lots of questions. He’d look at the parents for answers, but Kaitlyn answered them all. The doctor was amazed.

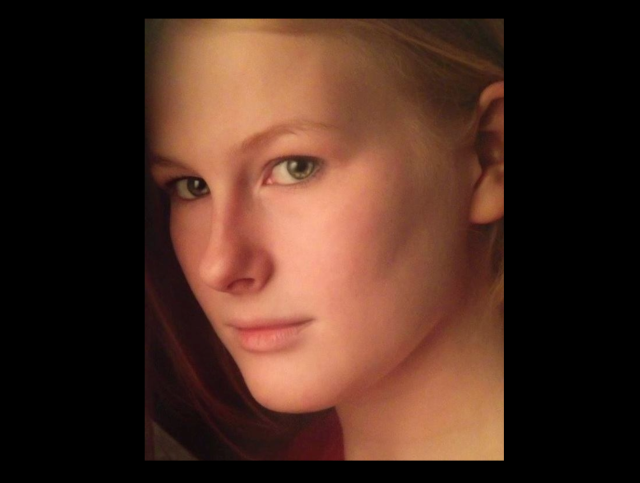

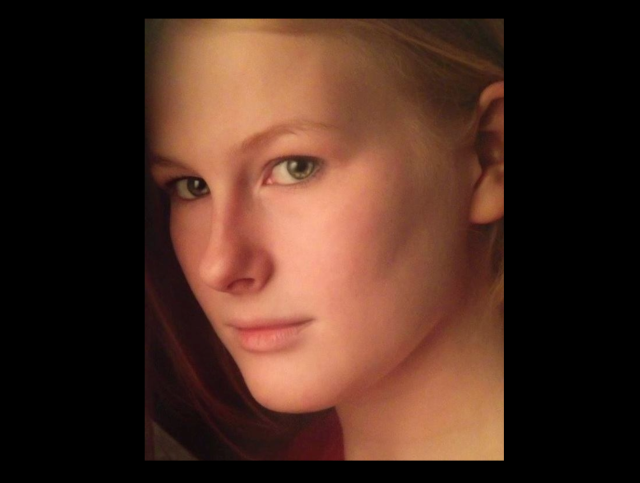

This is Kaitlyn in high school. A deep thinker, an artist, a poet. I met her extended family in North Carolina. They claim, “Kaitlyn was one of the happiest people on this Earth.”

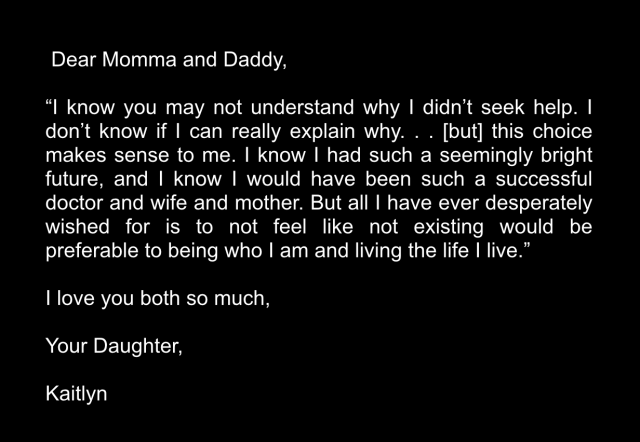

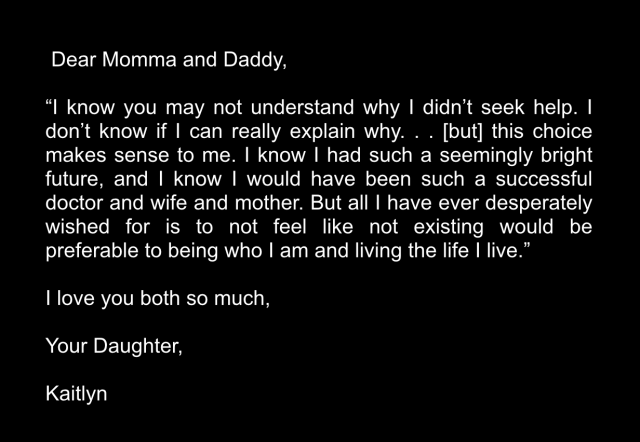

Here’s Kaitlyn in med school. Just 23 years old and beginning her third year. An introvert with social anxiety, Kaitlyn always had a few close friends, but none in med school. Everyone was busy studying and “people just went their own way,” she told her mom. She was desperately lonely. Her perfectionism worsened. She went on a strict diet, started running marathons, and lost a lot of weight. She ran like 10-12 miles before class everyday and still excelled in med school, acing her Step One exam. Unfortunately she didn’t live to celebrate her results because she completed her suicide—a helium overdose—like a well-planned school project. She left a 2-page suicide note in which she claimed lifelong depression, but hid it to protect her family and herself.

As an aside, I believe that Kaitlyn suffered less from depression and more from “feeling different and isolated” due to her high intellect. She was raised in the poorest county in North Carolina was the smartest person around. Maybe she had hoped that when she entered medical school she would finally be with her tribe—a social circle of more like-minded intellectuals. But medical school rarely creates an environment for students to develop intimate friendships with one another. These young sensitive and brilliant people are left to fend for themselves in survival mode with an overwhelming amount of material to master in a short time with little emotional support. I can guarantee that many medical students cry themselves to sleep at night in their pillows. That’s what I did nearly every night my first year of medical school. I cried so much that one morning my eyelids were sealed shut. I couldn’t see anything when I woke up. I had to feel my way to the bathroom. Is this they way a civilized society trains its healers? Kaitlyn’s mother published her daughter’s suicide letter in a book she wrote about Kaitlyn. An excerpt:

Kaitlyn’s grieving mother—unable to recover from her daughter’s death—died by helium overdose one year later. I attended her funeral last month.

* * *

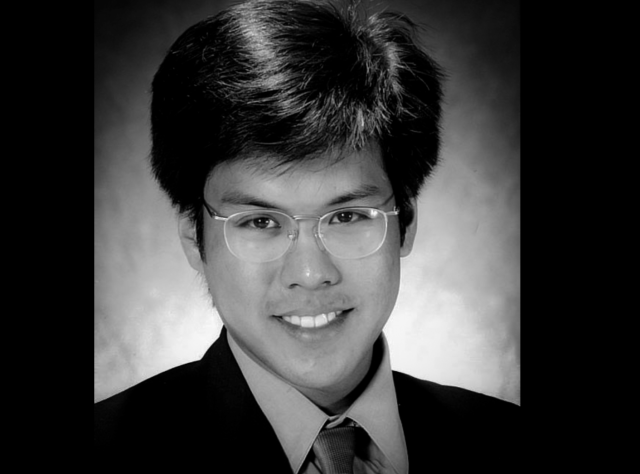

Here we have a spunky, happy 2-year-old girl who stood up to adults negotiating her way out of a bedtime, a bath time, and persuading her dad to get Slurpees and candy bars for dinner. Life was good until her first year of medical school.

Just a few months into med school she develops major depression due to what she calls “barbaric and inhumane medical training.” Years later, fed up with assembly-line medicine, she’s suicidal. The only difference between these cases is she survived and she’s on stage speaking today for the other 3 who can’t.

* * *

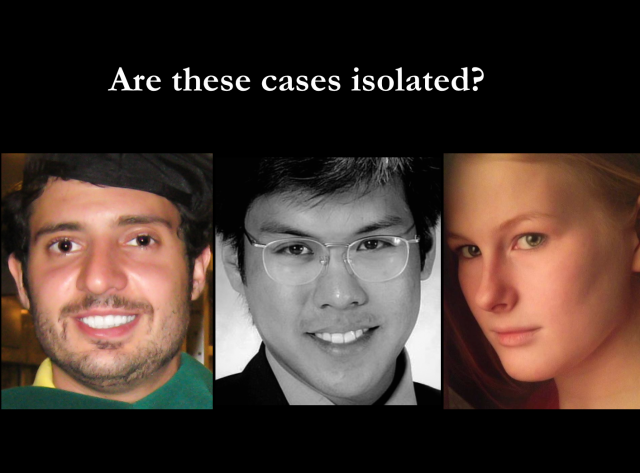

Our cases are not isolated. All brilliant, sensitive people who felt alone in a highly competitive and inhumane environment. All sleep deprived working or studying over 80 hours week. All hid their depression and appeared highly functional until their suicides and all left notes because we’re trained to do and we’re so darn responsible!

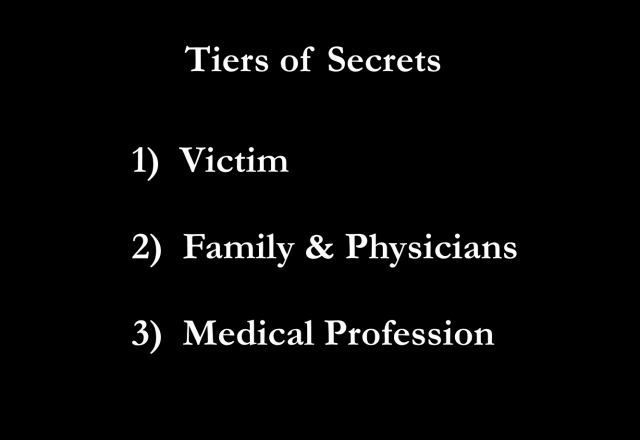

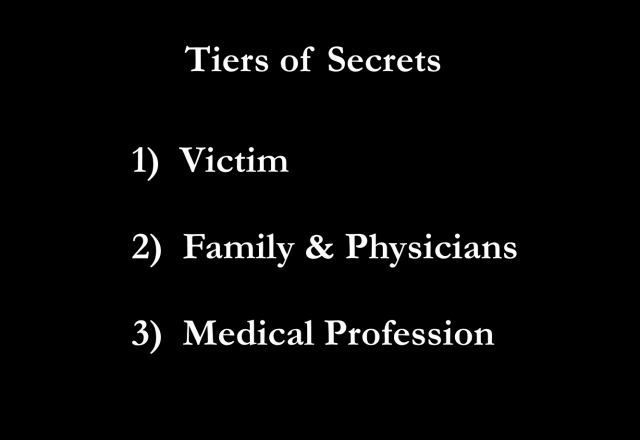

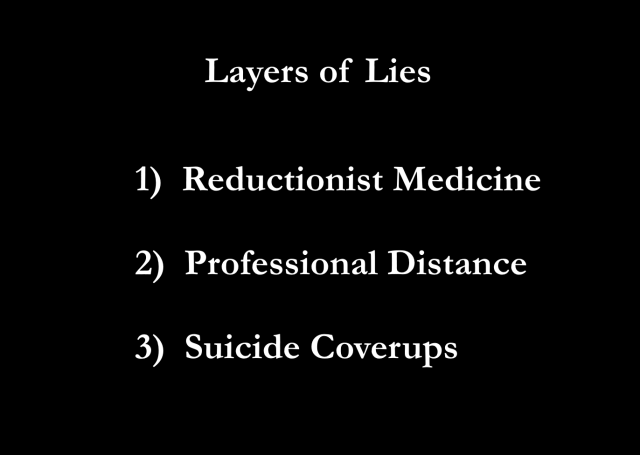

The secrets start with victims who are ashamed. Families remain silent to safeguard their reputations. Physicians hide suicides from patients who never find out why they can’t get a follow-up appointment with their doctor who left the clinic so suddenly. Physician suicide is medicine’s darkest secret and our code of silence is maintained by layers of lies.

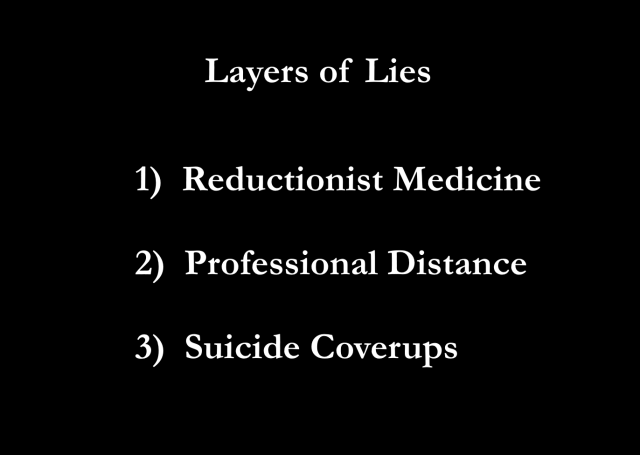

Reductionism is the opposite of holism. Reductionism leads to body-mind-spirit disintegration. While reductionist medicine has led to scientific advances, it’s fatally flawed. It separates us from our hearts and souls which is what gives our lives meaning and keeps up wanting to live here on Earth. Professional distance is far from protective. Vulnerability is strength. When we’re authentic with our patients and ourselves, we build resilience and connections with other people here on Earth. And the suicide coverups . . .

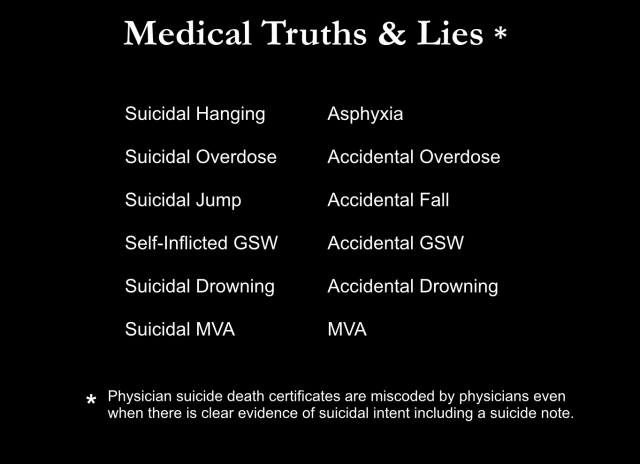

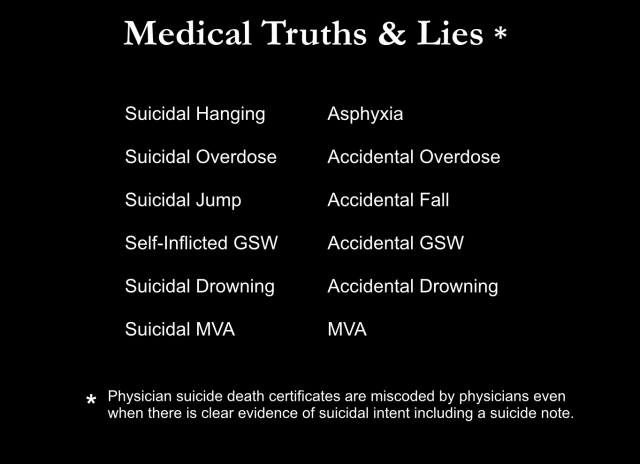

It’s a medical game of truths and lies. Death certificates are miscoded even when there’s a suicide note! A suicidal hanging becomes asphyxia, a suicidal overdose is suddenly an accidental overdose, a self-inflicted gunshot wound is officially an accidental gunshot wound, a suicidal motor vehicle accident is just another motor vehicle accident.

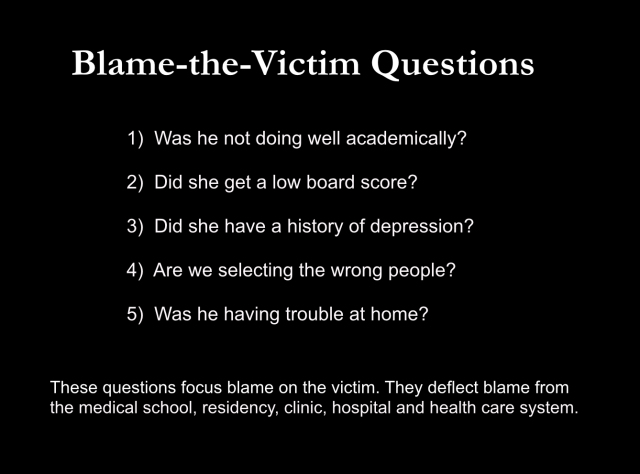

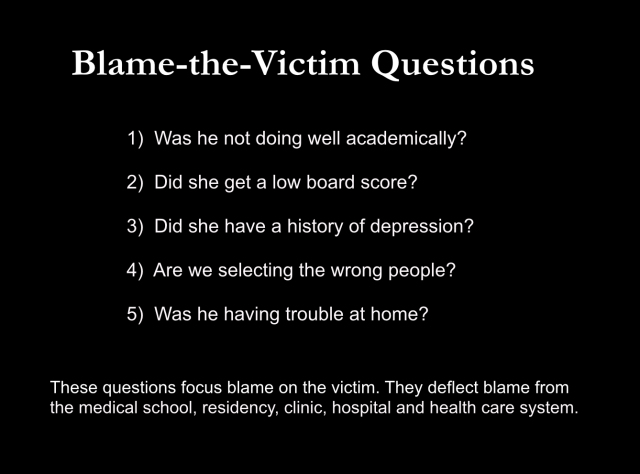

Meanwhile those in the know whisper blame-the-victim questions: Was he not doing well academically? Did she got a low board score? Are we selecting the wrong people for medical school? These questions focus blame on the victim, not the health care system.

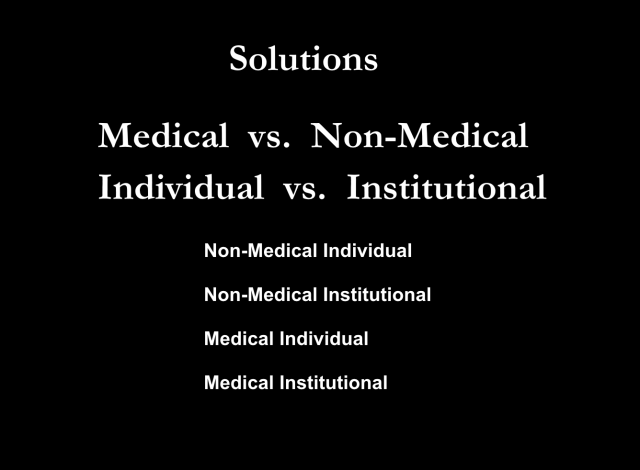

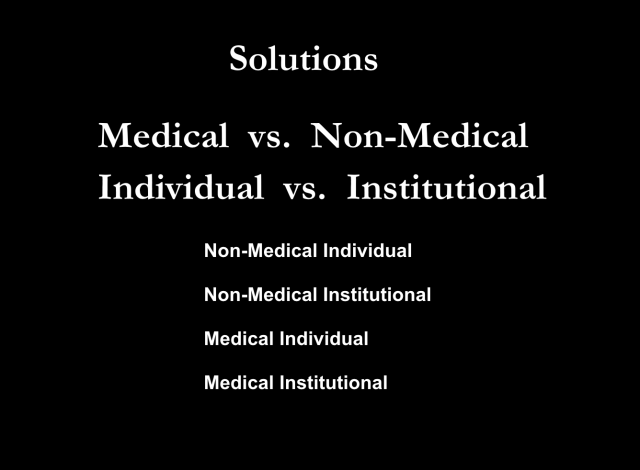

So what are the solutions? Solutions come from individuals or institutions inside or outside of medicine.

Non-medical individuals—the general population of non-physicians. Except for Greg’s parents who are aware of the occupational hazards of medicine, families had no idea their child was at high risk of suicide until the police called to tell them their child was dead. Compelled to act, Vincent’s mom starts a foundation that sponsors an annual lecture on mental health for residents at Vincent’s school. Kaitlyn’s mom writes her heart out online in a blog and on social media sites. She supports struggling medical students online. Ultimately she publishes a book examining suicides in the exceptionally gifted like her daughter. She asks all 171 medical schools in the United States if they would like a copy. Thirty got a copy. Should we rely on grieving mothers—suffering in isolation as were their children—to solve this?

Non-medical institutions like the media could instantly stop the secrecy and alert the public about the high risk of suicide in medical students and physicians. Because sending your child to medical school or a surgery residency is not like sending your kid to law school or to cashier at Walmart. It’s more like sending your kid to Iraq or Afghanistan and it requires a completely different level of vigilance. I spent two hours on the phone with Kaitlyn’s dad the other week. A sweet, sweet man. Not the kind of guy who would ever blame anyone else for his problems. I asked, “If Kaitlyn worked at Walmart, would she and your wife still be alive?” He says, “Yes. Medical school has cost me half my family.”

Medical individuals—that’s me and you questioning these deaths, and Greg’s mom seeking audits of PHPs for fraud and abuse.

Lastly medical institutions. Kaitlyn’s school started a fund in her name for donations to their wellness center so that presumably Kaitlyn’s classmates could seek the help that she didn’t. Vincent’s yearly lectures continue. But what else can we do?

Let’s compare how we handle physician suicide with say. . . umm . . . human rabies. Since the 1900s, annual human rabies deaths in the US have gone from 100 to just 2 per year. How did we do this? Not by grieving mothers launching “rabies awareness campaigns.” Not by donations to a wellness program. Not by a yearly lecture series. And not by miscoding rabies deaths as the flu!

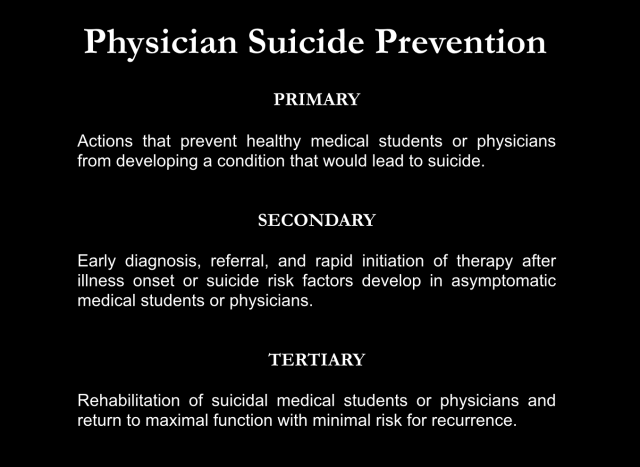

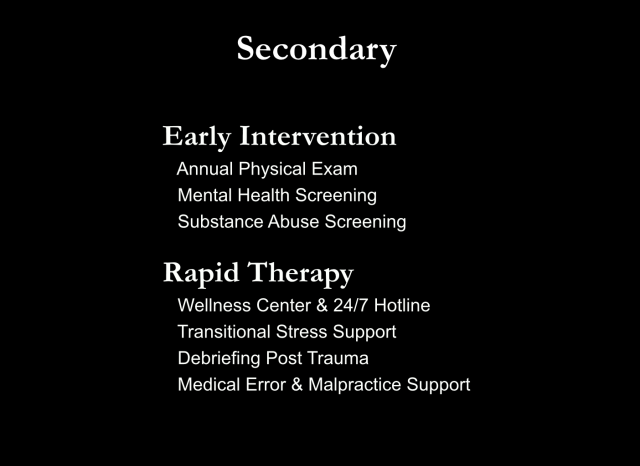

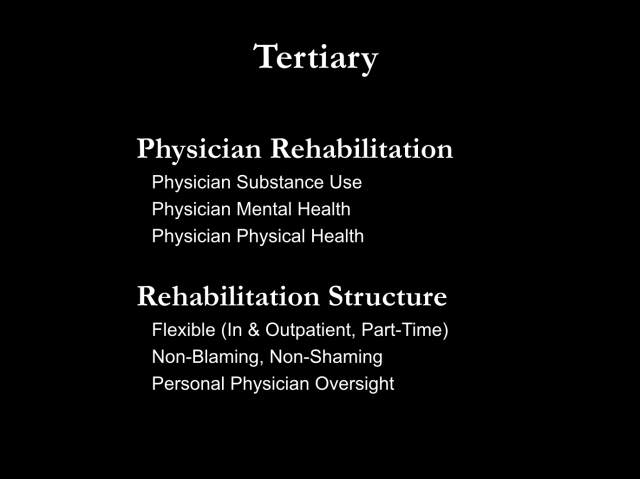

Here’s how we did it: medical institutions took this on methodically using science—primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies.

We spend over $300 million annually to prevent human rabies. The cost per human life saved ranges from $10,000 to $100 million. What do we spend on medical student and physician suicide prevention?

Since eradicating the terrestrial canine rabies variant in the US, 90% of the 2 deaths per year are transmitted from wildlife—mostly bats then raccoons. If we can deliver over 6 million oral rabies vaccine baits yearly to raccoons (and I’m talking about guys dropping these from low-flying planes over the Appalachian Mountains and dudes running through dark urban alleys), we’ve gotta be able to do something for med students. Right? We’re way easier to find than raccoons. We’re already in the hospital!

Right now while I’m standing here on stage we are actively tracking rabies in raccoons, bats, skunks, foxes, cats, dogs, cattle—even mongooses in Puerto Rico, but we’re not tracking the numbers of suicides in medical students and doctors. Do you ever get the feeling you might be less important than a Puerto Rican mongoose?

Here’s what scares Kaitlyn’s dad. Now I want to preface this with something else I learned about Kaitlyn’s mom who also suffered from depression. I asked Kaitlyn’s dad when his wife developed depression. Get ready for this. He told me it was after she completed nursing school in her 30s when she worked in a nursing home with a high census in which she was witnessing unsafe conditions for patients—and staff. She was normal before nursing school. Okay. Normal. Like medical students who start med school with their mental health on par with their peers. Then something happens during medical training to doctors—and nurses.

This is what really scares Kaitlyn’s dad. He tells me, “I got one child left. She’s in nursing school. I hope she’ll beat the odds. I can’t handle another.” This man has a real risk of losing more people in his family than we lose in a year to rabies! What are we doing? For him? For medical students? For us? Here’s what we should be doing:

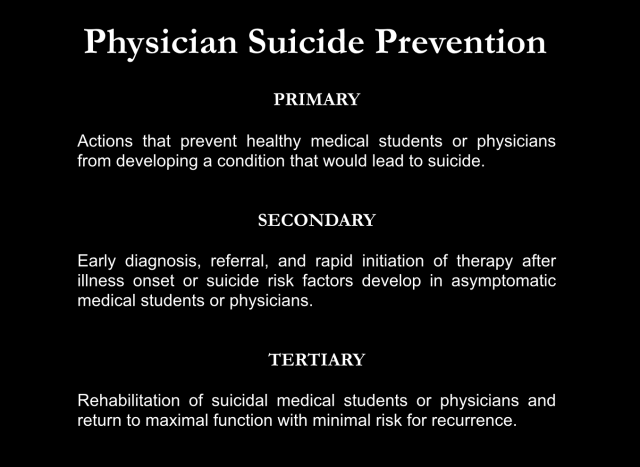

First: prevent healthy medical students and doctors from getting conditions that lead to suicide. Second: Early diagnosis, referral and therapy. Third: help suicidal medical students and doctors rehab.

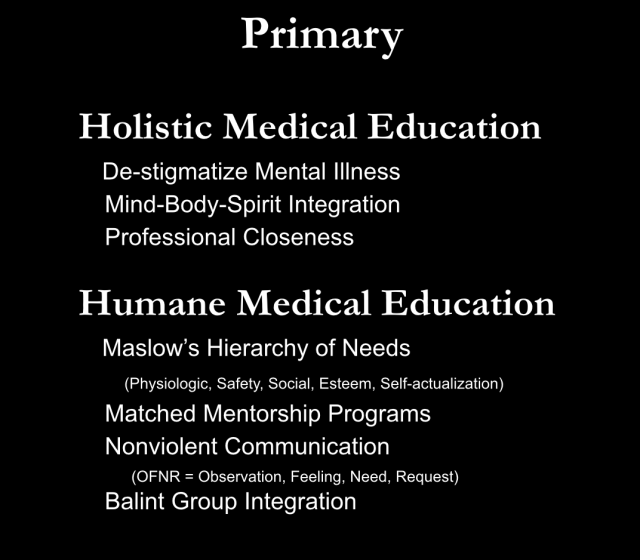

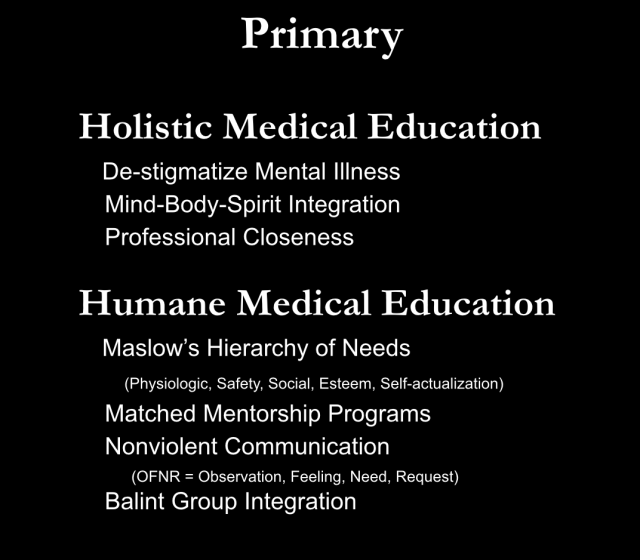

Let’s start with a holistic and humane medical education that de-stigmatizes mental illness.

The goal: help medical students be the self-actualized doctors described in their personal statements for which they were accepted into medical school in the first place. We know how to grow happy and healthy people. This is not some sort of secret. Follow Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Begin by meeting physiologic needs with adequate sleep, time to eat and bathroom breaks. Simple. Basic. Ya know? Meet safety needs with a safe workplace without bullying or abuse. Social needs can be met by allowing students to feel part of a community with time for intimate friendships. And finally, self esteem needs. Medical students should feel honored and respected for their contributions and level of mastery in medicine. Not belittled. Not shamed. Not pimped. Not hazed. This is 2014.

Meet social needs with Matched Mentorship Programs. Use match.com technology to match first year medical students with second years—and physicians within their specialty of interest. Match Day should be the first week of medical school. Don’t wait until fourth year for Match Day. These people need friends. Now. We should not allow medical students like Kaitlyn to die from extreme loneliness. Meet safety and self-esteem needs using nonviolent communication (NVC) which is based on the premise that every behavior is an attempt to meet a need. We can try to change others’ behaviors by using shame and blame or we can listen and educate compassionately. If you hear a doctor raise his voice at Vincent, would you pass by unsure of what to say? Meet the conflict with confidence using NVC using a simple 4-sentence sequence—a stated observation, feeling, need, and request.

Observation: I heard you speaking loudly to Vincent. Feeling: I feel concerned, because . . . Need: I need everyone be respected in this hospital. Request: Would you be willing to lower your volume and speak with more consideration for Vincent’s feelings?

Meet social and self-esteem needs with Balint groups. These are small group clinical case presentations that focus on the patient-physician relationship and enhance our ability to care for patients. Balint groups are usually led by a doctor with some experience in facilitating these groups and/or a psychologist/counselor. These groups are easy to start. If you want some training, I’d recommend the American Balint Society. Has anyone here ever done a Balint group? (Lots of family docs raise their hands in the room).

If Vincent could have attended a Balint group, he might have shared, “This week I saw a 30-year-old male who presented with injuries after jumping from a 3-story window after raping a young girl. I was tachycardic and I had trouble maintaining eye contact . . .” Vincent would have the chance to share feelings and get feedback in a safe environment. Offer Balint groups at lunchtime and meet physiologic needs too since students do need to eat! Ya know, give them a Subway sandwich or something to share.

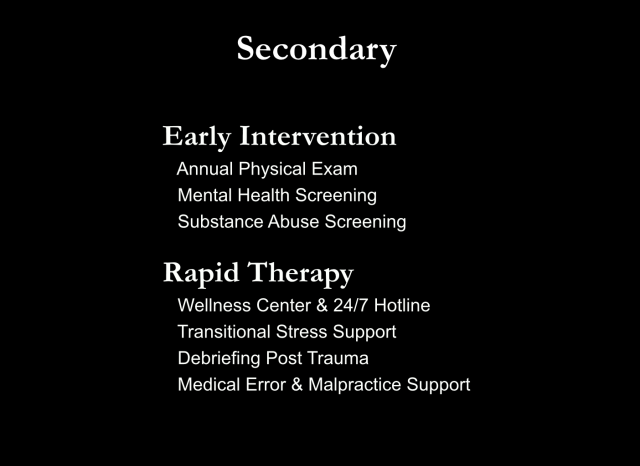

Early intervention begins with a yearly physical. In Kaitlyn’s second-year physical her doctor might have said, “I see you lost 20 pounds since first year and you’re getting up at 5:00 am to run 10 miles before class. How are things going for you?”

Every medical school needs a 24/7 helpline staffed by medical students. We learn to do blood pressures, ear and throat exams on each other, let’s learn emotional support too and give first and second years the real-world experience of being on call—for each other. Build in support for transitions from second to third year, traumatic cases, and medical errors. We’re all going to make an error and we should not have to feel like a failed perfectionist who can never be a good doctor. Again, medical students and physicians should not be left to cry themselves to sleep in their pillows alone at night with no support. That’s inhumane.

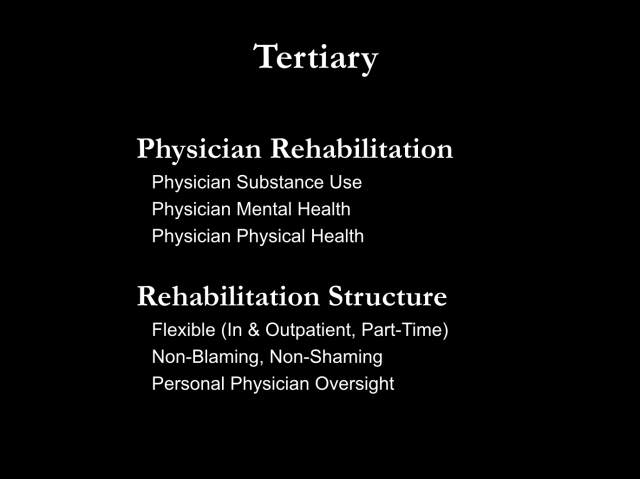

We need physician-specific rehab for substance use, physical, and mental health issues that are unique to physicians and medical students. Even medical students and residents with physical ailments feel ostracized from the group. The message usually goes something like this: “Let us know when you’re off the ventilator so we can put you back on the call schedule.” What kind of support is that? Rehab should be flexible, in town, with part-time work options. You know what kept Greg from drinking? His work. He loved working. Why send this excellent doctor 300 miles away? Greg shouldn’t leave town for inpatient rehab if local, output rehab is effective. And rehab should be non-shaming. When Greg called his mom (a psychiatrist) for help, his PHP therapist said, “Oh, you had to call your mommy?” What kind of treatment is that? We need personal physician oversight so our vulnerable colleagues are not abused and traumatized when they need help.

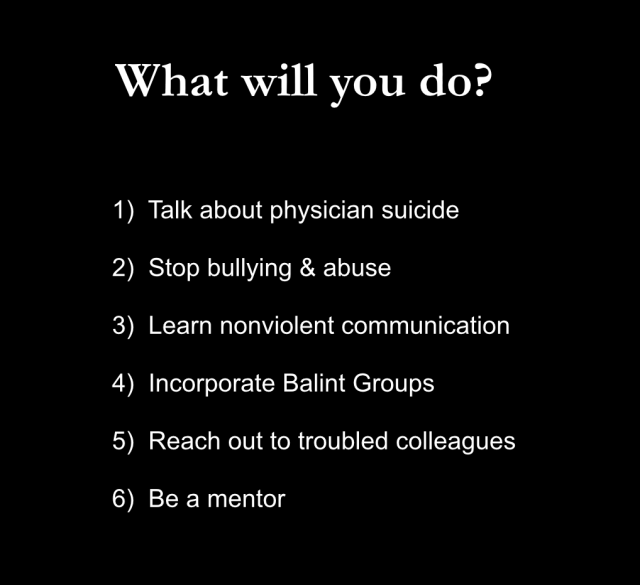

Would they be alive today? YES. Their deaths were 100% preventable. Every day we don’t take action, we lose another Kaitlyn, Vincent, or Greg. So what will you do?

1) Will you talk about physician suicide? If you lose a peer, will you hold an M&M conference or perform a psychological autopsy? A group of cyberspace docs recently asked me, “What gives you the right to perform a psychological autopsy? To go through these victims’ autopsies and suicide notes?” Well, these families reached out to me. I didn’t go looking for this. I didn’t even know I was doing psychological autopsies until I discovered the term in a suicide article. FYI: families with suicided children are eager for someone to take a sincere interest in their kids’ deaths. Would you be willing to honor their children? And prevent future deaths among your peers? Another gang of cyberspace docs wanted to know what kind of training I have that allows me to do these psychological autopsies. Do I have some sort of certificate that gives me the right to do this? I have no training. But my mom’s a psychiatrist. My dad’s a pathologist. Maybe that means I’m a natural at psychological autopsies. What training do you really need? Just take an interest in your dead colleagues. The only question you really need to ask is “WHY?”

2) Will you stop the bullying and abuse? We can all reach out to faculty who use shame-and-blame teaching, call attention to the violence, and offer alternatives. We do not need fear-based teaching to learn how to be healers.

3) Will you learn nonviolent communication? Vincent was inserted into violent crime scenes. Why speak violently to one another? NVC can reduce the trauma of our traumatic jobs. Let’s learn and then teach NVC. It’s easy. I learned in an hour online. Plus my ex-husband’s last girlfriend teaches it and I hired her for a private lesson. Takes about an hour—or at max two. Every medical school, hospital, and clinic should teach their students, physicians, staff—even administrators and CEOs how to speak with kindness and compassion.

4) Will you start a Balint group? All medical students and physicians would benefit from a weekly lunchtime case conference, a structured release valve for the trauma they have witnessed. Vincent and his peers could have processed their feelings and eaten. I offer monthly retreats in which physicians often (spontaneously and without prompting) start crying about cases from years ago. One doc in her late 50s broke down about a miscarriage she witnessed over 20 years ago. She was just so happy that she could finally cry about it! She hadn’t been able to cry in years. Really? We’re just supposed to just shove all this down day after day, week after week, year after year with no release valve? You can’t tell your spouse. Cases are confidential. Plus you’ll wear out your spouse. There’s a reason most people don’t go into medicine. They can’t handle this stuff. We can IF we have a way to process our feelings in real time before we start plotting our suicides. Please (I’m begging you) start a Balint group in your clinic or hospital. You could save lives.

5) Will you reach out to troubled colleagues? Doctors like Greg won’t just come up to you and say, “I’m suicidal.” But he might say, “I had a rough day.” (That’s doctorspeak for I NEED HELP!) When docs e-mail me their troubles, I call them back immediately. Sometimes 30 seconds after they hit the “send” button on their computers. They’re shocked. I respond,” When you’re on call, you call patients immediately. Right? Why don’t we do that for each other?”

6) Will you be a mentor? At the time of Kaitlyn’s death she was dating a man in Michigan who was a 99% match on OkCupid. Kaitlyn needed a matched mentor in her own town—at her own school. Someone to watch over her. Could that have been you?

There’s so much we can do. I don’t care what you do as long as we do something. So will you go out on a limb to save a doctor? To save the people who dedicate their lives to saving others? And if you are suffering, will you seek help? Standing at the town meeting, I went out on limb. I didn’t just tell folks I was an unhappy doctor. I told my entire town I was depressed and suicidal. I begged strangers to help me design an ideal clinic. And define an ideal doctor. I had lost my way. They told me an ideal doctor has a big heart and a great love for people and service. And an ideal clinic is a sanctuary, a safe place, a place of wisdom where we can learn to live harmlessly, listen with empathy and observe without judgement. It’s a place where a revolution starts where we rediscover our priorities with relaxed appointments, smiley-face balloons and fun flannel gowns—a lady at the town meeting even volunteered to make them for me. Then a bearded guy in the back of the room raised his hand and asked a question I’ll never forget, “Is it possible to find a doctor who’s happy?” I collected 100 pages of written testimony, adopted 90% feedback and we opened one month later. That was 10 years ago. I’m happy now. All because I asked for help.

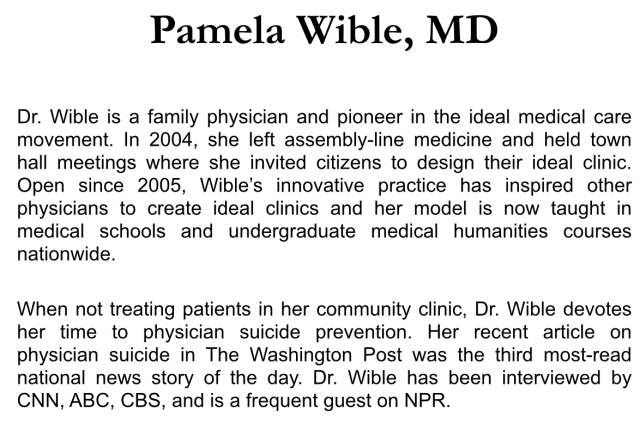

Pamela Wible, M.D., pioneered the first ideal clinic designed entirely by patients—the original “Patient Centered Medical Home.” She was once a suicidal doctor and now dedicates her life to helping medical students and doctors who are disgusted with, depressed by, and feeling suicidal about their once-beloved careers in medicine. There is hope! Come to the next physician retreat (premeds & med students welcomed). For all upcoming events, contact Dr. Wible.

Pamela Wible, M.D., pioneered the first ideal clinic designed entirely by patients—the original “Patient Centered Medical Home.” She was once a suicidal doctor and now dedicates her life to helping medical students and doctors who are disgusted with, depressed by, and feeling suicidal about their once-beloved careers in medicine. There is hope! Come to the next physician retreat (premeds & med students welcomed). For all upcoming events, contact Dr. Wible.

Dr. Wible: Welcome to Physician Suicide 101: Secrets, Lies & Solutions.

Dr. Wible: Welcome to Physician Suicide 101: Secrets, Lies & Solutions. I’m a family physician born into a family of physicians. My parents warned me not to pursue medicine. So I went to medical school. Ten years later, I’m unhappy with the direction of my profession (and I’m not the only one). Then I get this crazy idea: what if I ask for help? Not from the profession that wounded me. Just from random people on the street. So I hold a town meeting and ask patients to help me—design an ideal medical clinic. I promise do whatever they want as long as it’s basically legal. That’s going out on a limb.

I’m a family physician born into a family of physicians. My parents warned me not to pursue medicine. So I went to medical school. Ten years later, I’m unhappy with the direction of my profession (and I’m not the only one). Then I get this crazy idea: what if I ask for help? Not from the profession that wounded me. Just from random people on the street. So I hold a town meeting and ask patients to help me—design an ideal medical clinic. I promise do whatever they want as long as it’s basically legal. That’s going out on a limb.

Pamela Wible, M.D., pioneered the first ideal clinic designed entirely by patients—the original “Patient Centered Medical Home.” She was once a suicidal doctor and now dedicates her life to helping medical students and doctors who are disgusted with, depressed by, and feeling suicidal about their once-beloved careers in medicine. There is hope! Come to the next physician retreat (premeds & med students welcomed). For all upcoming events,

Pamela Wible, M.D., pioneered the first ideal clinic designed entirely by patients—the original “Patient Centered Medical Home.” She was once a suicidal doctor and now dedicates her life to helping medical students and doctors who are disgusted with, depressed by, and feeling suicidal about their once-beloved careers in medicine. There is hope! Come to the next physician retreat (premeds & med students welcomed). For all upcoming events,