(Listen in above to a rerecorded keynote—due to a fire alarm during event—or read transcript of Dr. Wible’s presentation below)

Michael Phillips MD: Good morning everybody. I want to introduce the lectureship and remind everybody who Gil was. Gil was originally from Philadelphia and then moved to Oregon where he joined The Gastroenterology Clinic, which at the time was the only GI-specialty clinic in Oregon. He became one of the preeminent gastroenterologists well-loved by patients and staff alike and known for his outstanding humor, his clinical skills, and patients who absolutely adored him. I continue to take care of patients that he took care of 20 to 25 years ago and they still think of him as their gastroenterologist. I’m just kind of standing in. That’s the kind of guy Gil was. Gil really dedicated himself to education. He was Outstanding Teacher of the Year twice—a testimony to who he was. He died unexpectedly at the age of 50 [on a ski trip, not a suicide]. In response to his untimely passing, we established this lectureship 20 years ago. We’re here today to commemorate him and to continue to use his legacy to help facilitate our practice and humanity in taking care of patients.

It’s really with a great pleasure that I get to introduce our speaker today, Dr. Pamela Wible. Pamela is family physician born into a family of physicians. Her parents actually warned her not to become a physician. Shortly into her first year of medical school, she experienced the adverse effects of medical education on her own mental health. It wasn’t until 2012 after losing three colleague physicians to suicide that she began to investigate the mental health crisis among medical students and fellow physicians.

For the past six years, Dr. Wible has reported on doctor suicides and human rights violations in medicine. Her articles have been picked up by major media including The Washington Post and Time Magazine. She’s the author of the bestselling book, Physician Suicide Letters—Answered (free copies available today). Dr. Wible has two TED Talks on doctor suicide. She’s been interviewed on primetime investigative television and featured in a new award-winning film Do No Harm that’s currently being screening at hospitals and medical conferences internationally.

In between treating patients as a solo family physician in Eugene, Oregon, Dr. Pamela Wible continues to run a free doctor suicide hotline that’s been in operation since 2012. Today, she’ll share the results of her investigation into more than 1100 physician suicides and reveal simple truths and solutions to prevent the loss of our healers. Please welcome Dr. Pamela Wible. Thank you.

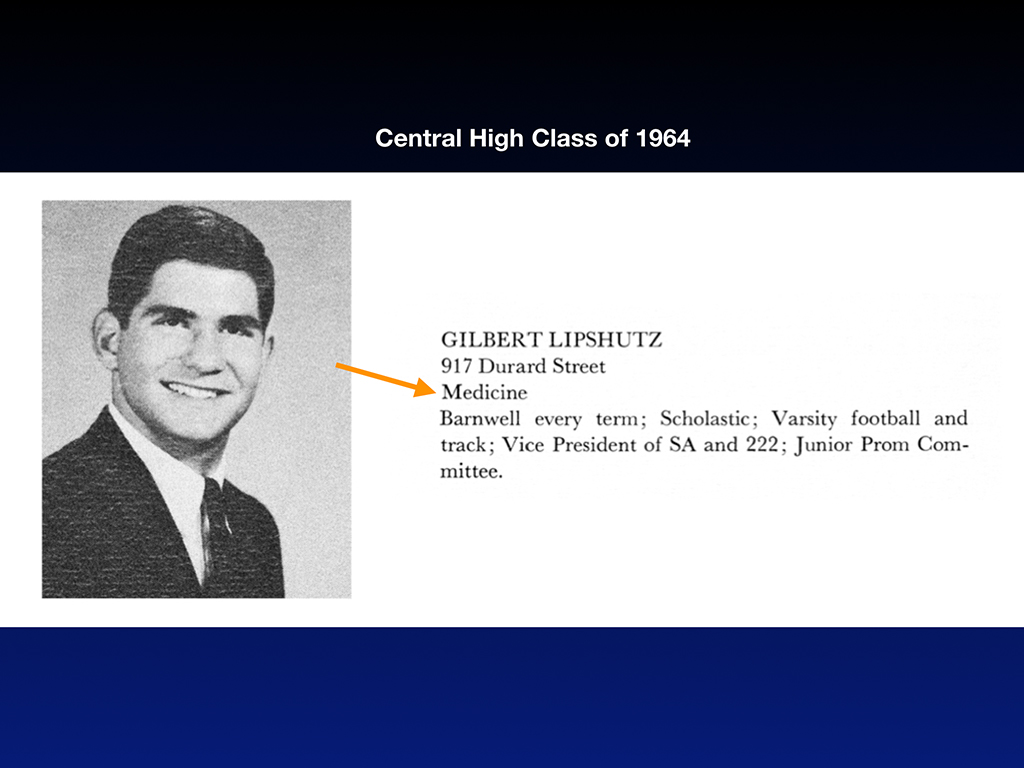

Pamela Wible, MD: Thank you all so much for being here. I want to thank Providence for hosting this event and taking on this topic of doctor suicide. Though I never met Gil in Oregon, our paths did sort of cross in Philadelphia. Turns out my dad and Gil attended the same high school where Gil was actually the vice president of his graduating class.

There he is. Teacher of the Year at Providence as a young guy before he had the mustache. Gil knew from early on that he was headed for a career in medicine. He declared that right away at Central High.

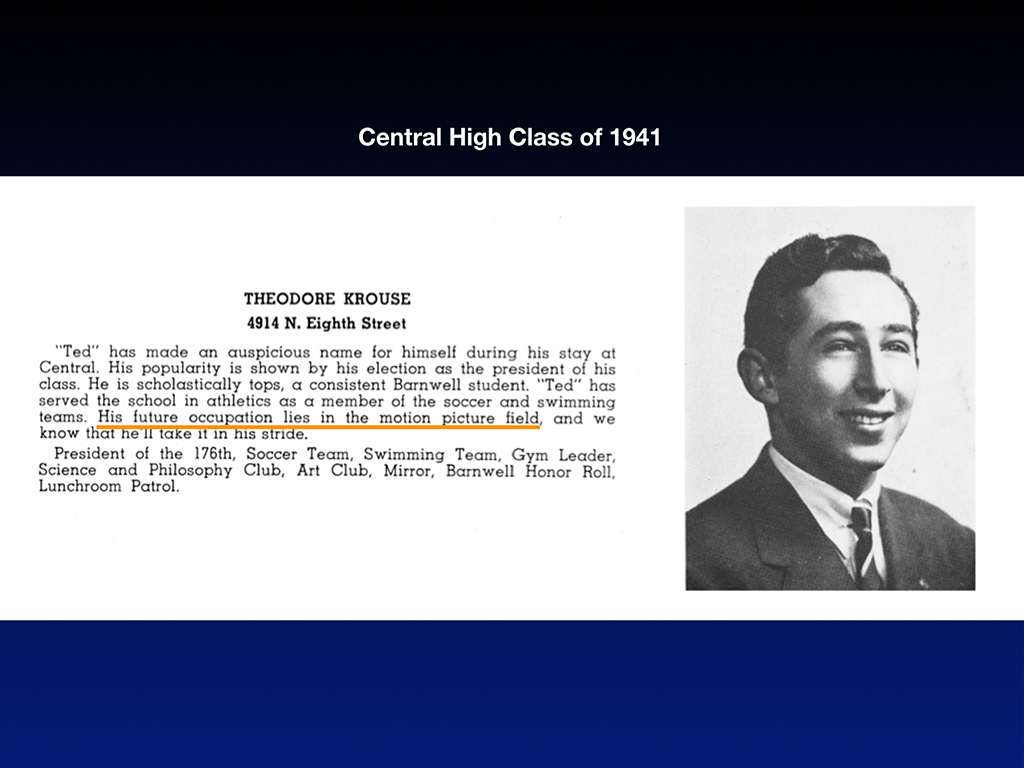

Unlike Gil, my father assured his classmates as the president of his class that his future occupation would be in the motion pictures.

Like a good Jewish boy he relented to parental pressure and became a doctor. Both Gil and my dad did some of their training at Hahnemann in Philadelphia. Both pursued internal medicine. How odd is it that I’m invited to do this lectureship and my father and Gil have such parallel paths in medicine.

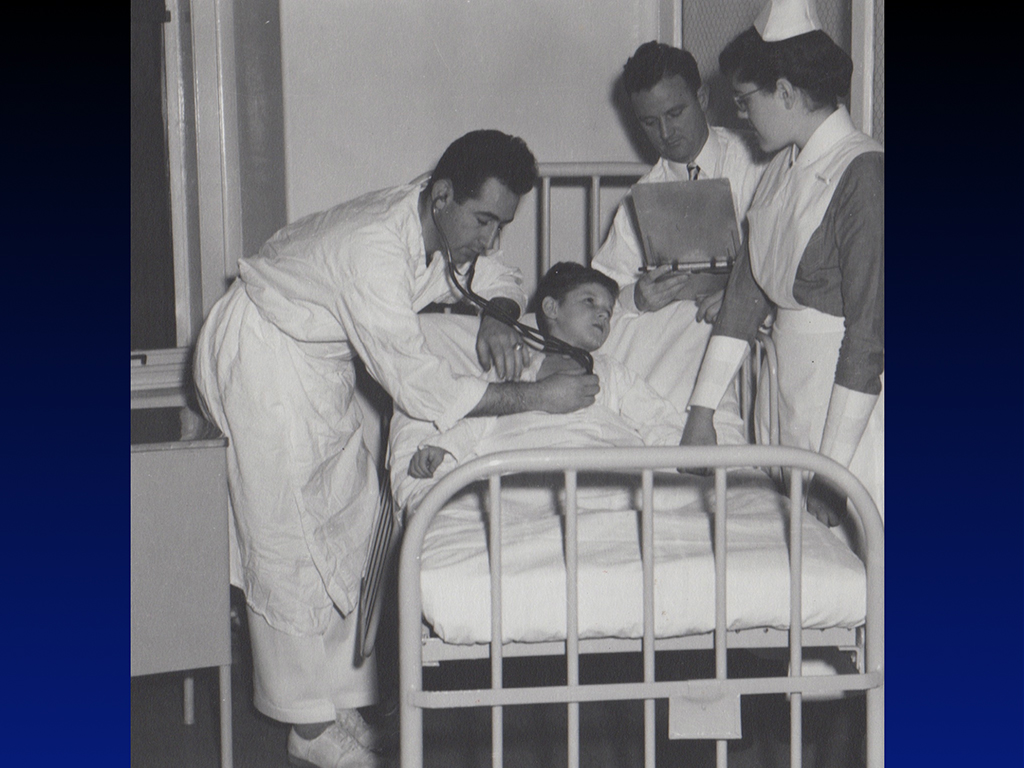

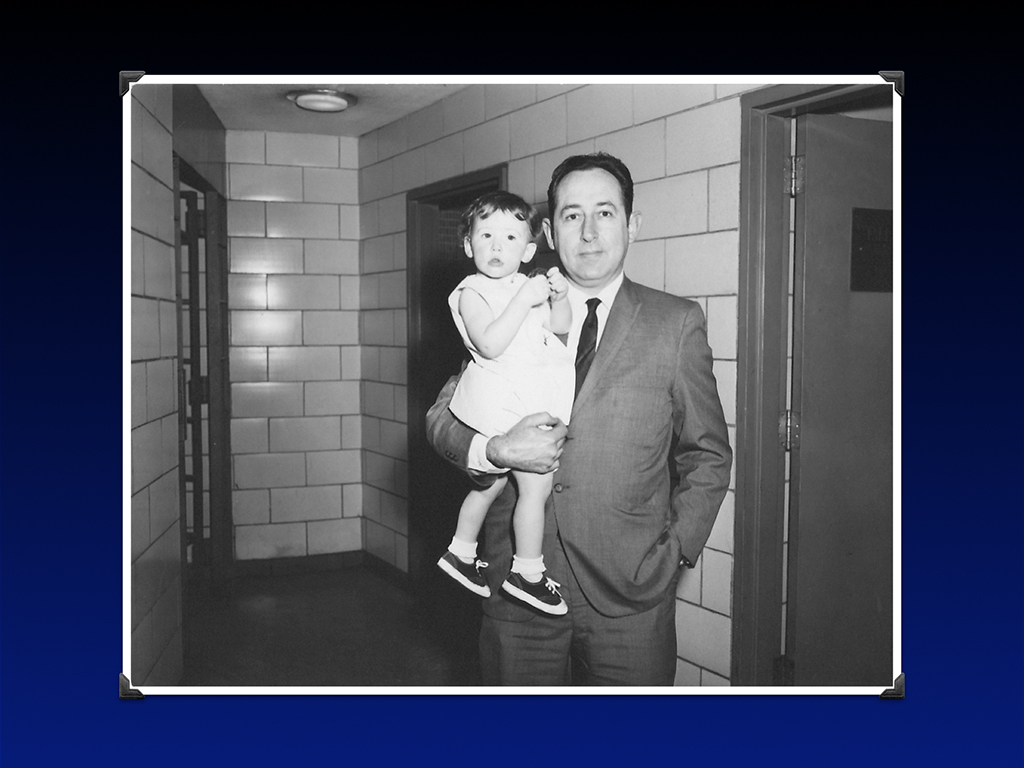

Unlike Gil who died at the height of his career, my father practiced medicine for 62 years and retired at 87. He died four years ago this morning at 91. My dad ignited my interest in medicine. Here I am following him around in the hospital. With physician parents I grew up in the hospital hallways back when they didn’t care if your kids crawled through the morgue with you. I don’t see many physicians’ toddlers wandering the hospital hallways today. Too bad. I had so much fun playing with the paraffin in the pathology department and looking at this huge glass jar with all the bullets and foreign bodies he found in patients (that I thankfully inherited after he died).

Dad’s a pathologist. I think the human drama of running a small neighborhood internal medicine practice was a little bit too much for him, so he chose a more predictable patient population in the morgue. My mom is a psychiatrist so I tagged along as a child at the state hospital. So I spent my time with mom hanging out with the seriously mentally ill and with my dad I got to hang out with dead people. Neither of my parents needed stethoscopes so I inherited all their equipment from med school too. I developed this love for medicine and a fearlessness about mental illness and death because of the unusual experiences I had with my parents—amazing for a blossoming young doctor, but for my siblings morgue visits were horrifying and traumatic.

Unlike my father, I’m much more of a rebel. Since I was warned not to pursue medicine, here I am graduating from medical school and becoming a solo family physician (who still doing house calls and practices medicine the old-fashioned way—which is kind of a rebellious thing to do in 2018!).

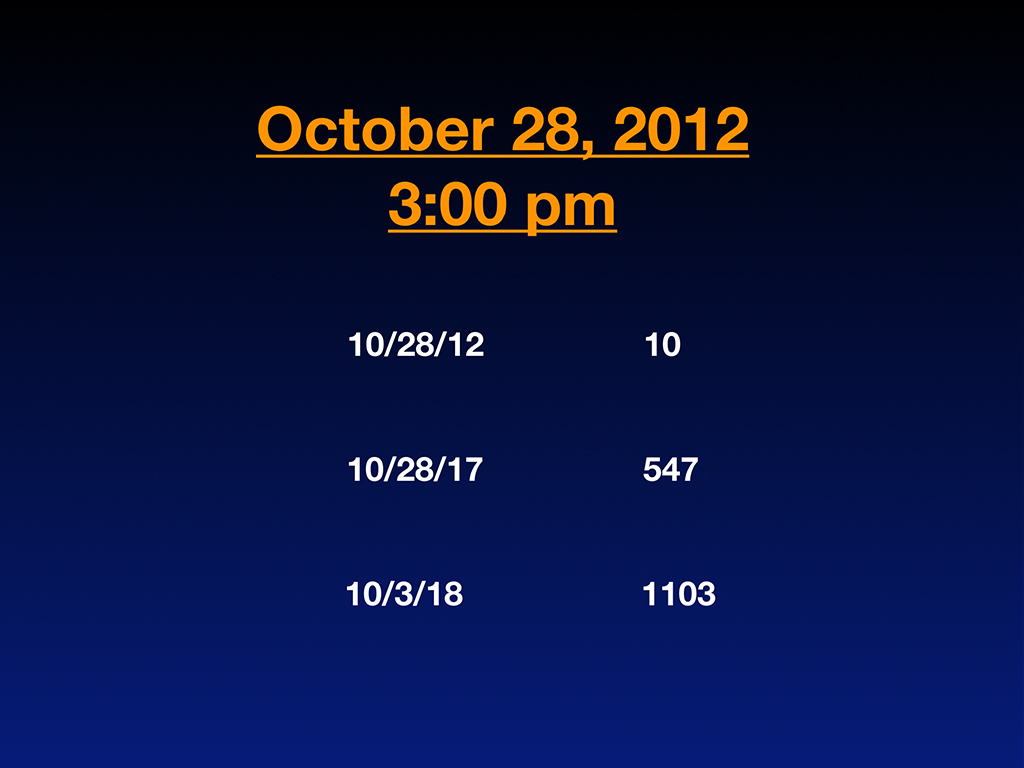

I was living the happily-ever-after life of an old-fashioned family doc in the sweet town of Eugene, Oregon until October 28th, 2012 at 3:00 p.m. when my entire life got turned upside-down. I found myself sitting in the second row of a memorial service for our third physician suicide in our small, idyllic little town full of farmer’s markets, organic food, and friendly hippies. Sitting at this memorial service, I started to count on my fingers the number of doctors that I had personally lost to suicide in my life and/or who died under suspicious circumstances that I thought maybe were suicides covered up with the classic euphemisms.

Within a few minutes, I had counted 10. Startling for me in my early 40s—the prime of my career. So I did what I needed to do to get a handle on this epidemic—I gave up knitting and mosaic mural artwork and began tracking doctor suicides as a hobby. I became completely obsessed with why so many doctors were dying by suicide. Two of the doctors on that list of 10 were men that I dated in medical school who died by suicide (not while I was dating them I want to make that clear) but later on when they were married. They died at 39 and 44 leaving wives and young children behind.

Because I am so vocal and such a prolific writer on doctor suicides, I ended up well-known among my peers for my investigation into doctor suicide and soon people began telling me about more and more doctor suicides. Five years later, I ended up with 547 cases submitted to me by physician colleagues and family members. I never went looking for these suicides. They were submitted from people calling me saying, “Hey, I want you to know my neighbor shot himself in the head a year ago. I was in my backyard. I heard the shot, I saw the police come. The family’s not really talking about it, but here’s the backstory and I want you to know what really happened to this cardiologist.”

So I end up with this list—an informal suicide registry where I’m tracking by name, specialty, date, method, and location of suicide, plus any extenuating circumstances. Now I have a very deep understanding of why my peers chose to die. And cases keep coming to me almost daily. Now I have 1103 doctor suicides that I’ve personally investigated by talking to family members, friends, the last boyfriend, and medical school classmates.

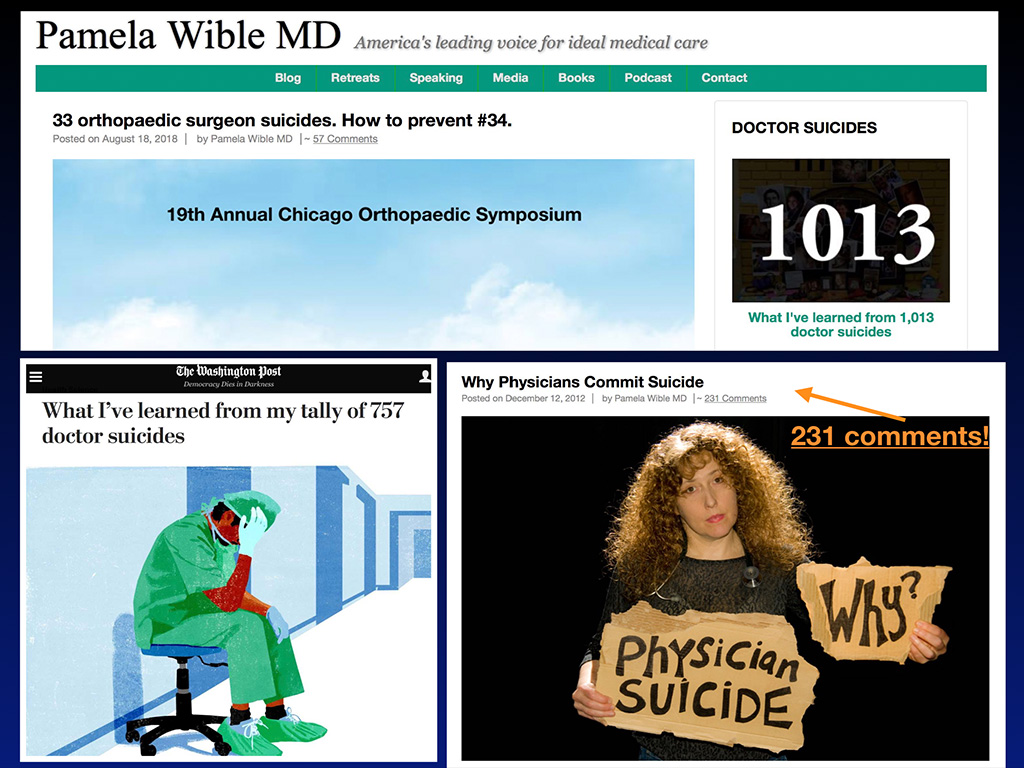

With so much content, I’m discovering themes. Here is my blog where I began to share results of my investigations. Full disclosure: Personally I’m so obsessed with this topic because I was a suicidal physician myself in 2004. I thought I was the only one. I had no indication that other doctors were suffering. I felt like the oddball, the sensitive one. Maybe I was too idealistic. I just had no idea physician suicide was such an epidemic.

Professionally, I feel called to be a healer. As a scientist and physician, it is my obligation to research why my peers are dying. So I started blogging about suicide and my blog (that nobody really read up until then) suddenly on December 12, 2012 when I published Why Physicians Commit Suicide ended up with 80 comments right away and now 231 comments. So the public response kind of egged me on to continue talking and writing about it.

Then my blogs started to get picked up by The Washington Post, like this one, What I’ve learned from my tally of 757 doctor suicides. That was how many cases I had on my registry as of January 13th this year. Here’s a screenshot of the top of my blog a month ago back when I had just over 1000 cases and reported on my latest data at my keynote at this orthopedic surgery conference. I was the only female physician speaker during this four-day orthopedic surgery symposium. I consider that a huge accomplishment. All the orthopedists only got 10 minutes to deliver their content and they gave me an hour on doctor suicide! There’s an indication that we’re making progress as a profession addressing doctor suicide.

So here’s a wall in my house covered with physicians and medical students who have died by suicide. Again, I’m taking this very personally and I’m in touch with many of their family members.

Now a bit about the scope of the doctor suicide crisis. We’ve known about the high rates of doctor suicide since 1858 when first reported in the UK. Now, 160 years later, the root causes of these suicides remain unaddressed. That’s because we don’t really understand the root causes of a taboo topic—hidden for more than a century. Because as a culture we’re scared to say suicide out loud in and we’re definitely scared to say doctor suicide out loud.

Doctor suicide is a triple taboo. Death is not a topic anyone wants to discuss over dinner. Suicide is death suddenly in your face. Now doctor suicide—the people that are supposed to be helping us are dying by suicide too. This strikes terror in the hearts of patients and makes doctors feel vulnerable. It’s just a scary topic for most people so I’m taking this on because lives on the line that can be saved today by the way we behave with each other and our willingness to tell the truth about physician suicide.

Physician suicide is a public health crisis. More than one million Americans lose their doctors to suicide each year—just in the United States. Researchers say we lose 400 physicians per year to suicide (they believe this is an underestimate), yet 400 is the size of an entire medical school. The average medical school has 126 students in each class, and so that’s an entire medical school equivalent of physicians per year. Due to all the secrecy and underreporting—even death certificates that are completed as accidents when they are self-inflicted—doctor suicides are often well hidden. A physician in family medicine has a patient panel of 2,300 patients. The average emergency medicine doctor probably sees even more per year. Simple math on 400+ times 2,300+ and you’ve got a million patients who’ve lost their doctors to suicide (and that’s not including student doctors).

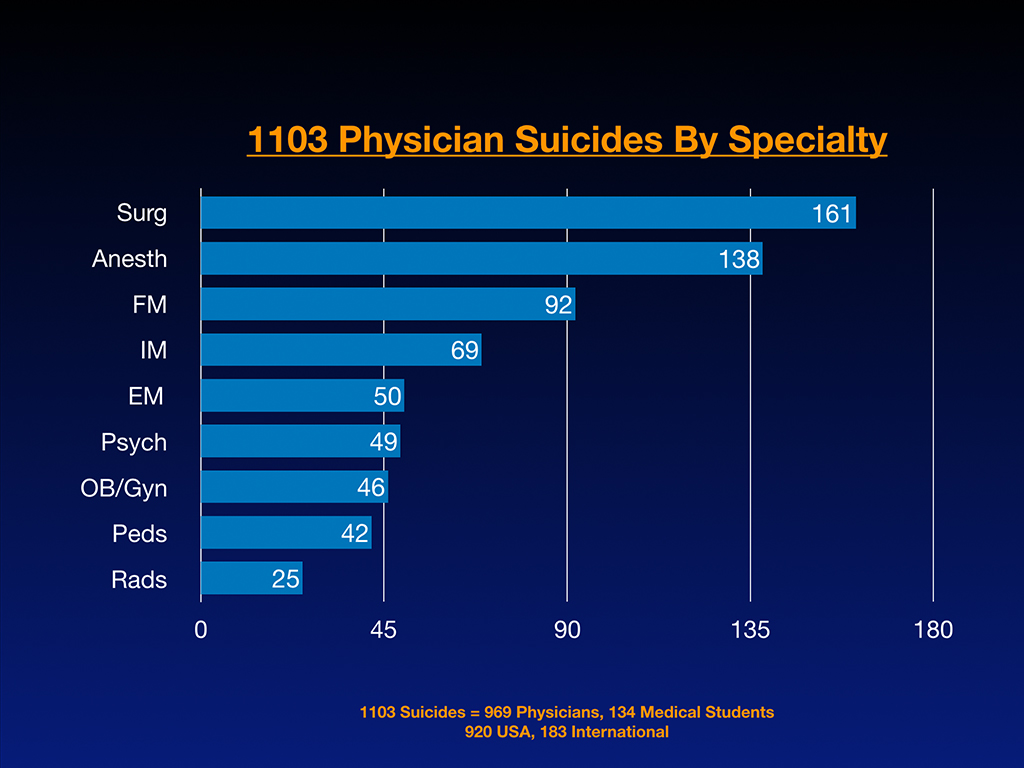

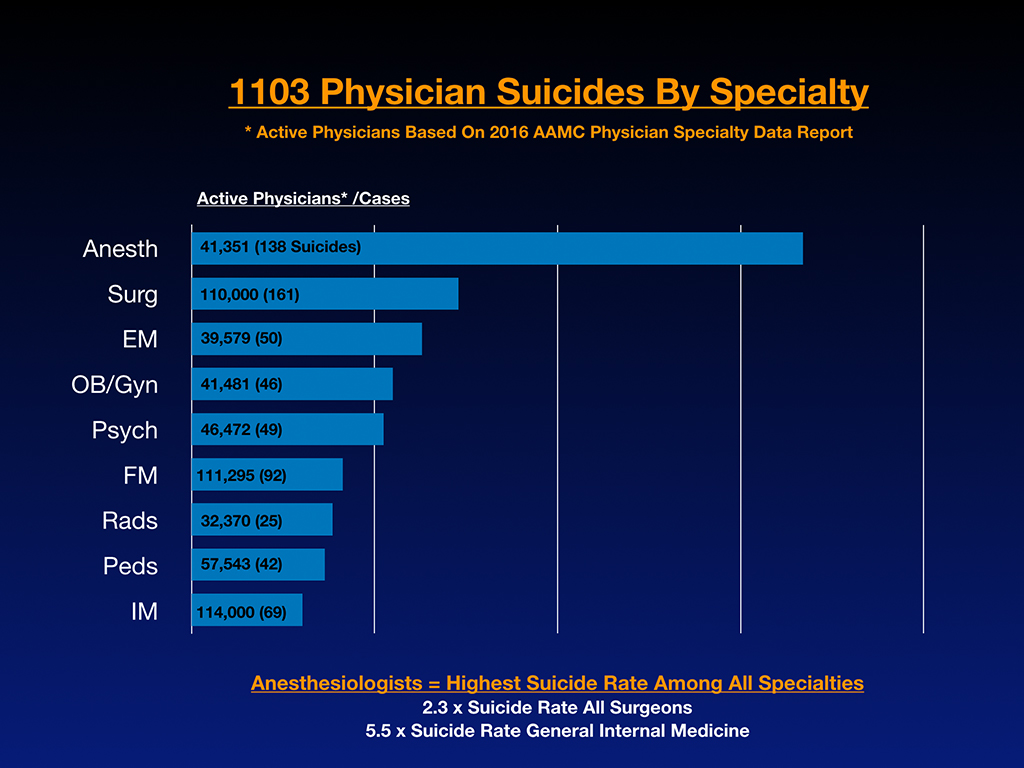

Here’s some raw data on more than 1100 cases I’ve received. Of 1103 suicides. 969 are physicians and 134 are medical students on the registry and 920 of these happened in the U.S. while 183 are international. People are contacting me from all around the world. Last week I was on a Skype call with a doctor form Israel telling me about the head of the department who died by suicide, as usual “happiest” guy and totally unexpected. When looking at raw registry numbers per specialty (and not accounting for size of specialty), surgeons are in the lead, then anesthesiologists, family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine, psych, ob/gyn, pediatrics, and radiology. However when evaluating these numbers based on active physicians per specialty we can see the real impact of suicide per specialty below:

These are numbers based on active physicians in the largest specialties. Now we start to see some really interesting trends. Anesthesiologists are really off the charts. Of the largest specialties, general internal medicine has the lowest number of suicides according to my 1100+ cases. Anesthesiologists actually have 2.3 times the rate of suicide of all surgeons (general surgeons plus all surgical subspecialties). Anesthesiologists have 5.5 times the rate of suicide of general internal medicine doctors.

Medical students with preexisting mental health conditions deserve informed consent about mental health risks per specialty. I have premed students calling me who’ve had previous suicide attempts or panic attacks that are poorly controlled right now and they want to go to medical school. They deserve to know this information just for their own sanity and survival.

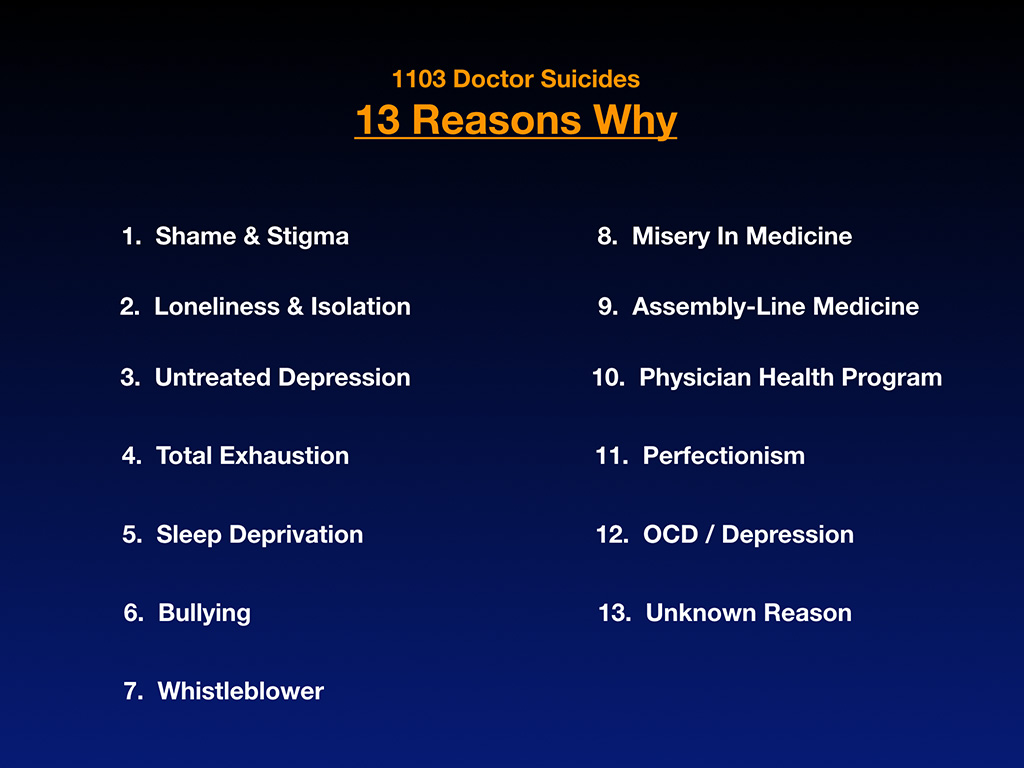

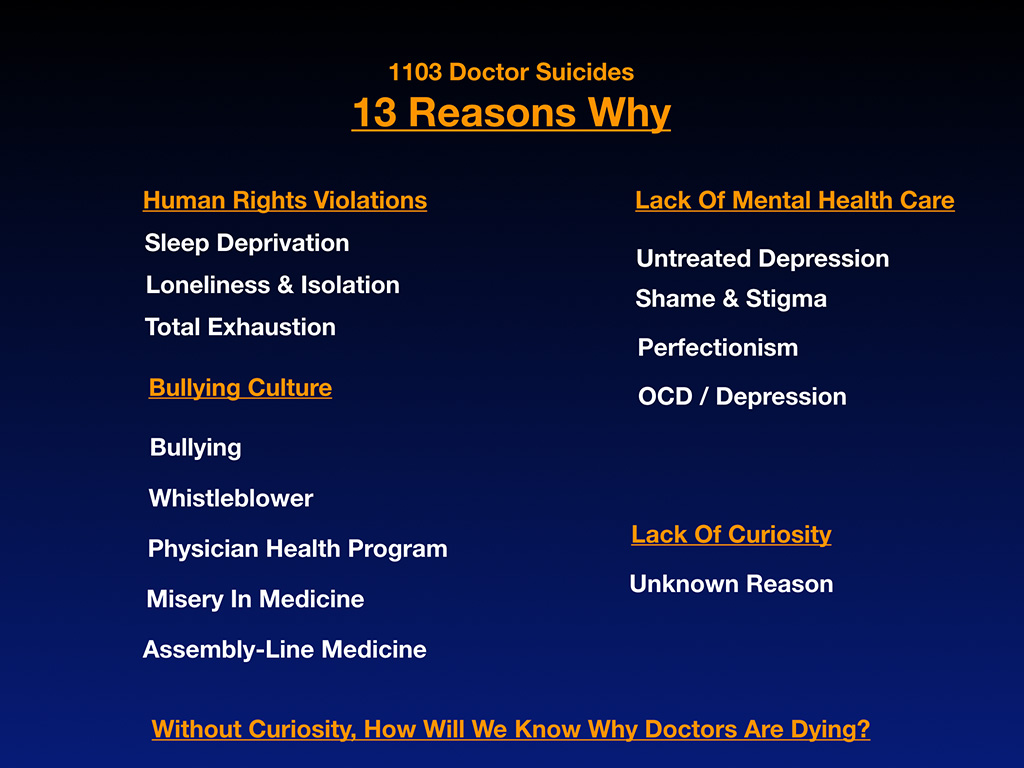

To fill in the gaps of this underreported epidemic, I’ll review 13 reasons why doctors die by suicide through case studies by introducing you to 13 our best and brightest colleagues who have died by suicide.

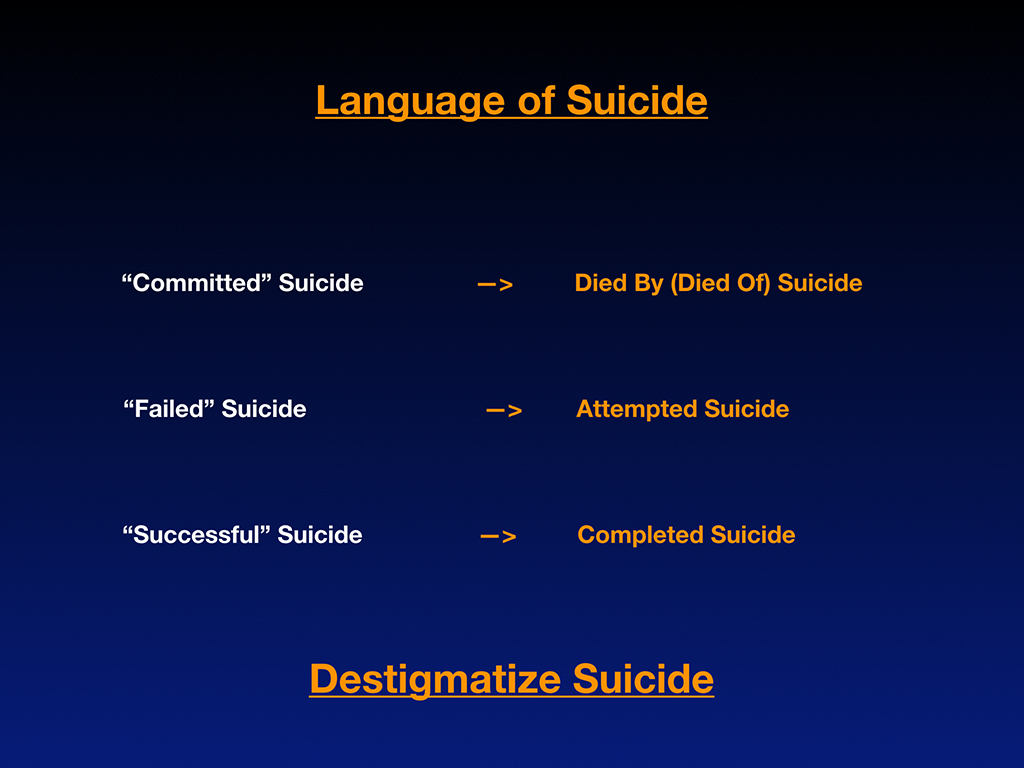

First, a quick recap on the language of suicide. Because this is such a taboo topic, people have been afraid to even say suicide aloud. By the way, at that memorial service that I went to they never said suicide out loud. Everyone knew that he shot himself in the middle of the day at Mount Pisgah in Eugene, so it wasn’t hidden. He’d had a public death in a public park, but nobody at the memorial service said suicide out loud. In the bathrooms and milling around, everyone kept whispering, “Why?” Everyone wants to know why and nobody will say suicide out loud. Imagine if we we were afraid to say diabetes out loud but we had to sneak into the bathroom to whisper about our diabetic patients. How far we would be with treating diabetics? Imagine if patients had to sneak out of town and pay cash and use paper charts to keep diabetes off the EMR. Insane. Right?

My plea here is let’s destigmatize suicide so we can actually discuss this crisis factually with data—and without such terror and shame. We can actually solve this problem. Because we don’t often know how to talk about suicide I’d like to encourage correct terminology.

“Committed” suicide is actually a very antiquated, stigmatizing way to discuss suicide because it makes it sound like a crime (like committed burglary or rape). Really suicide is a medical condition in which people are dying prematurely and should be discussed like every other medical condition—died by diabetes, died by heart failure, died by or of suicide. I know it’s hard because it’s like a knee-jerk reaction to say “committed” suicide. Even newscasters are still saying “committed” suicide, but I’ve been schooled on this through a psychiatrist who is the parent of a 29-year-old internal medicine physician who died by suicide. She was one of the first who commented on my blog Why Physicians Commit Suicide and she wanted me to know the title of my blog was stigmatizing. I didn’t know any better. I was just starting to discuss this myself and it was a great teachable moment for me, and so I’d like to pass that on to you.

Next, the idea of a “failed” suicide. How weird is it that when a physician attempts suicide and actually survives that should never be framed as a failure? Call that an attempted suicide in which we now have salvaged the person’s life by the grace of God. “Successful” suicide. To die as a 29-year-old internal medicine resident is not success. That’s a completed suicide which shouldn’t have happened in the first place. To prevent the next 29-year-old internal medicine resident from dying by suicide, I would ask you all to please destigmatize the suicide conversation.

Now I’ll share 13 case studies and 13 reasons why we’ve lost some very beautiful and brilliant people to suicide. I could talk about each of these amazing people for hours. Due to time constraints I’ll give just a thumbnail sketch of each case (some have been discussed in far greater detail in my other articles and keynotes).

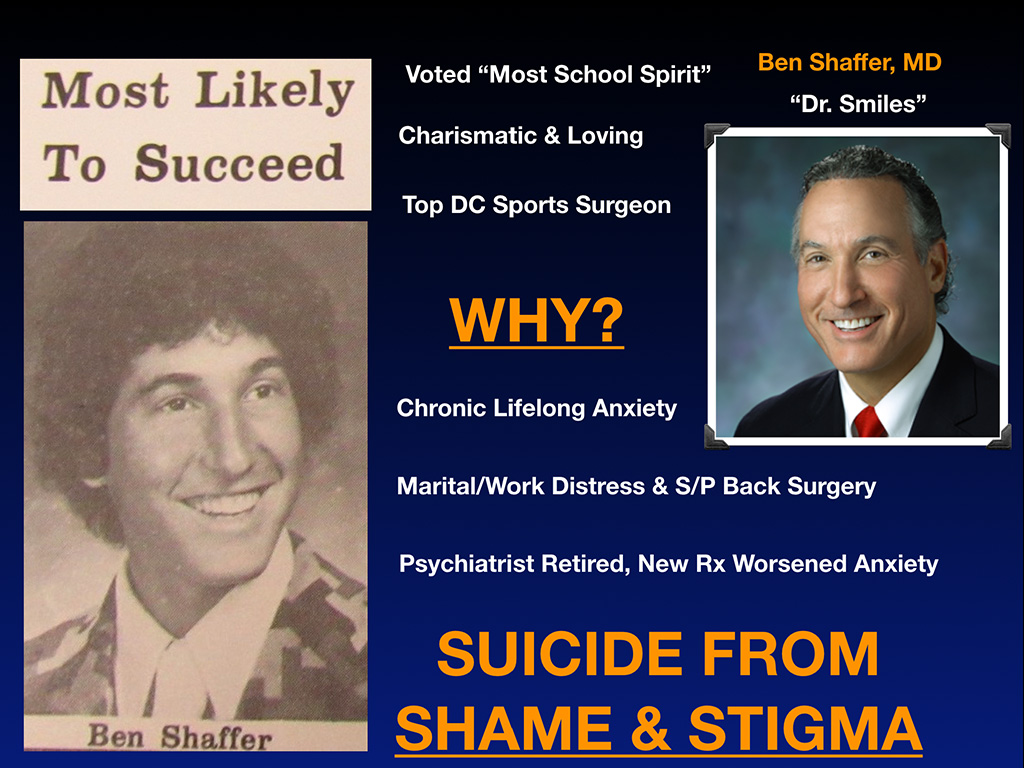

First meet Dr. Ben Shaffer. Ben’s sister just sent this newspaper clipping to me. Ben was voted Most Likely to Succeed in high school. That has a new meaning for her now. He was also voted Most School Spirit in junior high. You can see this guy is awesome, charismatic, loving. He was the top DC sports surgeon at the time of his death. They called him Dr. Smiles. Nobody had any idea he was suffering. Such a smiley guy cracking jokes up and down the hospital hallways.

Why is he now suddenly dead by suicide? What you didn’t see from his smile is his chronic lifelong anxiety. Plus he had marital and work distress, which I think we all have. That’s not unique to Ben. As a physician when you throw yourself into your professional life at the level at which demands are made on us, you will have personal life atrophy. I don’t think there’s a doctor in here who hasn’t had a strained marriage or relationship related to the commitment that we have to our profession. Plus he had work distress. Not unique to him. Reimbursement was going down and that puts stress on you when you’re in a private practice as an orthopedic surgeon. On top of that, he’d just had back surgery. He was dragging his foot and expected to have a complete recovery, but the whole process of having chronic anxiety added to his recent stresses and on top of that his long-term psychiatrist retired and passed him on to a new doctor who changed his medication regimen resulting in worsened insomnia and anxiety.

Ben knew he needed to be hospitalized. Instead he hanged himself on a bookcase at home rather than seek inpatient care. He died from shame and stigma. He was more concerned about his colleagues knowing that he would be on an inpatient psych ward. He did not want other professional team members to know. As a very high-profile guy in DC he was scared that everyone in town would know that he had mental health problems. And so, he chose to die instead. Unbelievable.

What I’m listing here is that final event among a cascade of events that happens over time. Notice how preventable these suicides are. On interviewing physicians who have survived suicide attempts (all male) I asked, “How long did it take between when you decided you would take your life and when you pulled the trigger, took the pills?” They said, “Three to five minutes.” So we have just a few minutes to intervene if we wait until the time of their suicide and perform some heroic salvage via 911 and chest compressions. It’s very hard to heroically insert yourself within those last three to five minutes of someone’s life. Meanwhile, there are thousands of missed opportunities over decades leading to those last few minutes of life. Let’s not waste one more early intervention opportunity. Please.

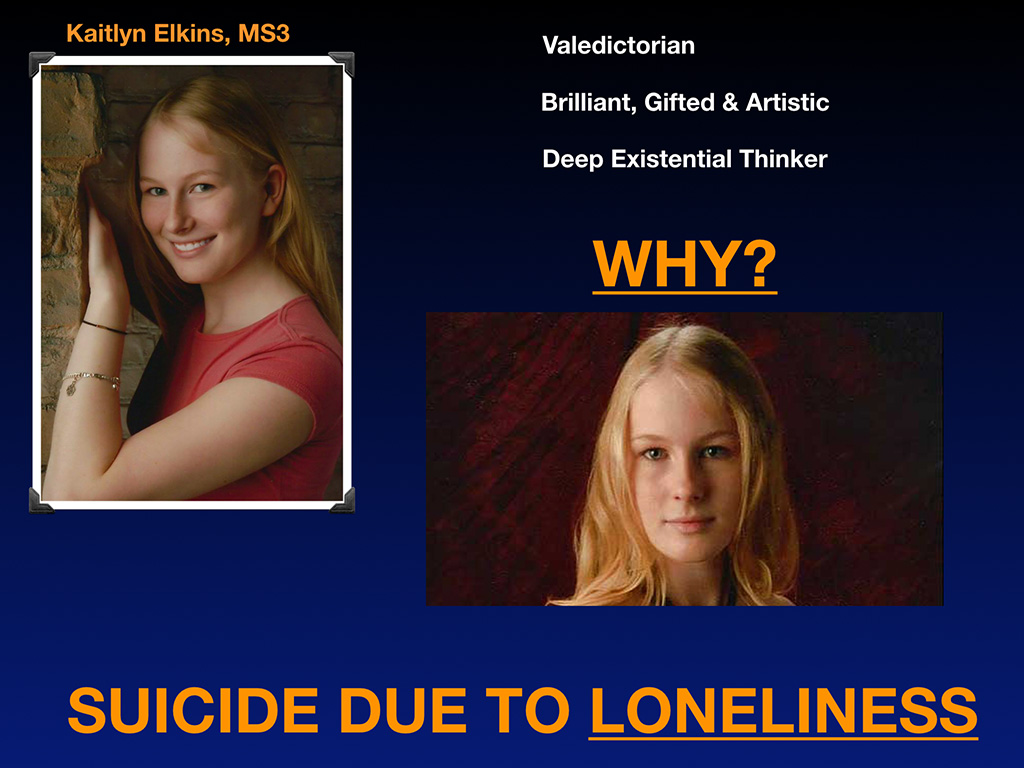

Here we have Kaitlyn Elkins, a third-year medical student. Perfect child. Everyone dreams of having a child like this. She doesn’t curse or drink or do drugs, and is home on time for dinner, straight-A student. Valedictorian. Brilliant, gifted, artistic. A deep existential thinker. She grew up in rural North Carolina, probably had the highest IQ for 100 miles around. Being a gifted person can be a lonely experience because you feel different from everyone else. You feel sort of more responsible than everyone else. You’re the president. You’re the valedictorian. You don’t really have a peer support group because nobody is like you. Life can be lonely.

Why did Kaitlyn end up dying by suicide as a third-year medical student near the top of her class? I believe she was hoping when she got to med school she could finally be with her tribe of like-minded, high IQ, deep existential thinkers. We are brothers and sisters in medicine. We are a family. We have a whole heck of a lot on common. Yet medical education is delivered in such a way that pits students against each other in a fear-driven atmosphere that is competitive, not collaborative, to the point where the first day of medical school they’ll welcome students with a threat: “Look around the room. Half of you won’t be here next year.”

Challenging to bond with each other under such threats. This woman ended up dying by loneliness, which is totally preventable. We can prevent this by changing the atmosphere. We could welcome first years into the family. The dean could pass out her cell phone number and say, “Hey, I’m here for you. You’re the cream of the crop. We won’t let you fail.“ Orientation could be a time for people to make lifelong friendships. We could start nurturing our gifted students instead of terrorizing them to learn—a horrific strategy for everyone and especially for gifted, sensitive people. Public humiliation and terror as a teaching tool is catastrophic for our mental health.

I became very close with Kaitlyn’s mom, who died by suicide a year later completely heartbroken that she lost her daughter. I ended up at her funeral. I have to tell you standing at a funeral where you see one headstone with that beautiful, blonde-haired, 23-year-old woman and then the pile of dirt and the casket of her mother who I’ve had a million phone conversations that I never met in person until I was next to her dead body with my hand on her casket—this is a scene out of a nightmare.

Her husband who’s the sweetest man, not a vengeful bone in his body, not an angry person, a very sweet kind guy, I hung out with the whole family for the afternoon after this memorial service, this devastated family in rural North Carolina. I asked him, “Do you think if your daughter worked at Walmart or went into real estate or did something else, do you think your family, your wife and your daughter would still be alive?” Sweet guy says, “Yes. Medical school has killed half my family.”

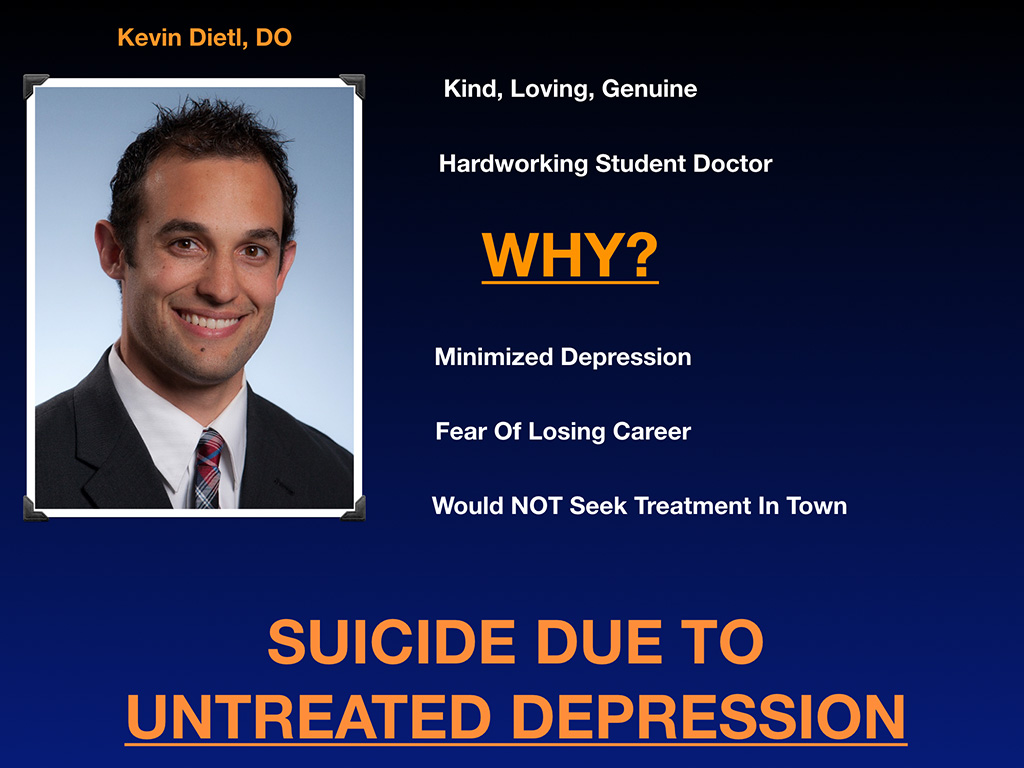

This is Dr. Kevin Dietl, a kind, loving, genuine, hardworking student doctor. He put in his best effort through medical school. Why did he die? He ended up depressed. He minimized it. His mother noticed and Kevin reassured her, “Mom, everyone in my class is depressed.” Probably true. So he normalized his depression as just what happens to all medical students. He feared losing his career. He didn’t want to seek treatment in town and didn’t want it on his record. He was three weeks away from graduating medical school. They gave him his degree posthumously. Three weeks away from graduation when he died from untreated depression by firearm. Nobody should be dying from untreated depression—especially when surrounded by such a high density of doctors all day long. Doctors saw that he was suffering and they just let him continue on his rotations (even though he was picking at his skin and having obvious signs of serious depression leading to a psychotic break).

Family members are startled when they find out about this epidemic after losing a child to suicide in medical training. They are under the assumption that sending your child to medical school will be one of the safest places for a student. In case of a medical emergency, these students are surrounded by doctors and hospitals. Paradoxically, it is just the opposite. Medical training and practice (though surrounded by medical professionals who could presumably help you) is a high-risk career for near-fatal and fatal mental health crises such as suicide. Like sending your child to Afghanistan, to an active war zone. Interestingly, a medical student who was in the military reported to me that she felt safer in Afghanistan during active sniper fire than she did in medical school.

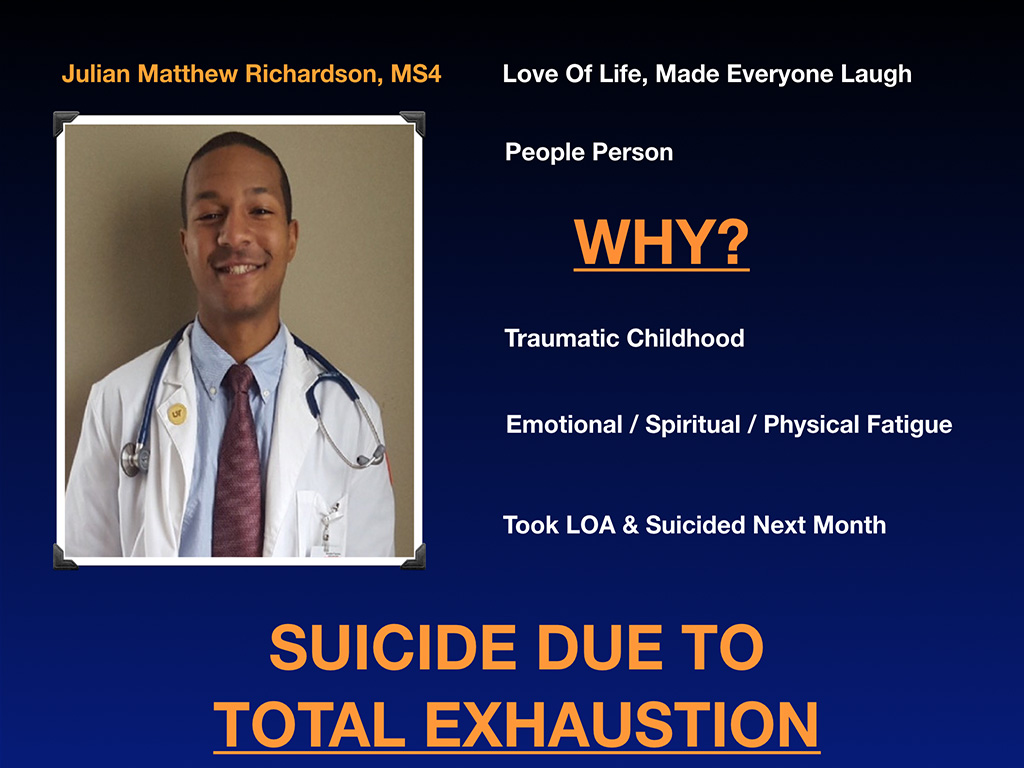

Meet Julian Matthew Richardson who had a love of live, made everyone laugh, was a real people person. Why did he die by suicide? I’m very close to his mother now who texts me multiple times a day with all sorts of pictures. She’s a reverend—a real spiritual, beautiful approach to life. Well, she revealed he had a very traumatic childhood. A lot of people who go into medicine have survived childhood trauma and for whatever reason, they’re attracted to emergency medicine often where they’re re-triggered every day at work through every case. Without mental health support, this could undermine your sanity. Julian felt very broken, like emotionally, spiritually, and physically fatigued just from medical training and what he was witnessing, He took a leave of absence and suicided the next month. He died from total exhaustion, according to his mother. I do believe this was absolute total emotional, spiritual, physical exhaustion and in part exacerbated by preexisting issues before medical school but medical training just opening theses wounds every day. One of the last things he said was, “Mom, they really don’t care about these patients.” He just felt like people weren’t getting their needs met. What he was witnessing was just too much for him. Julian was obviously not getting his needs met either.

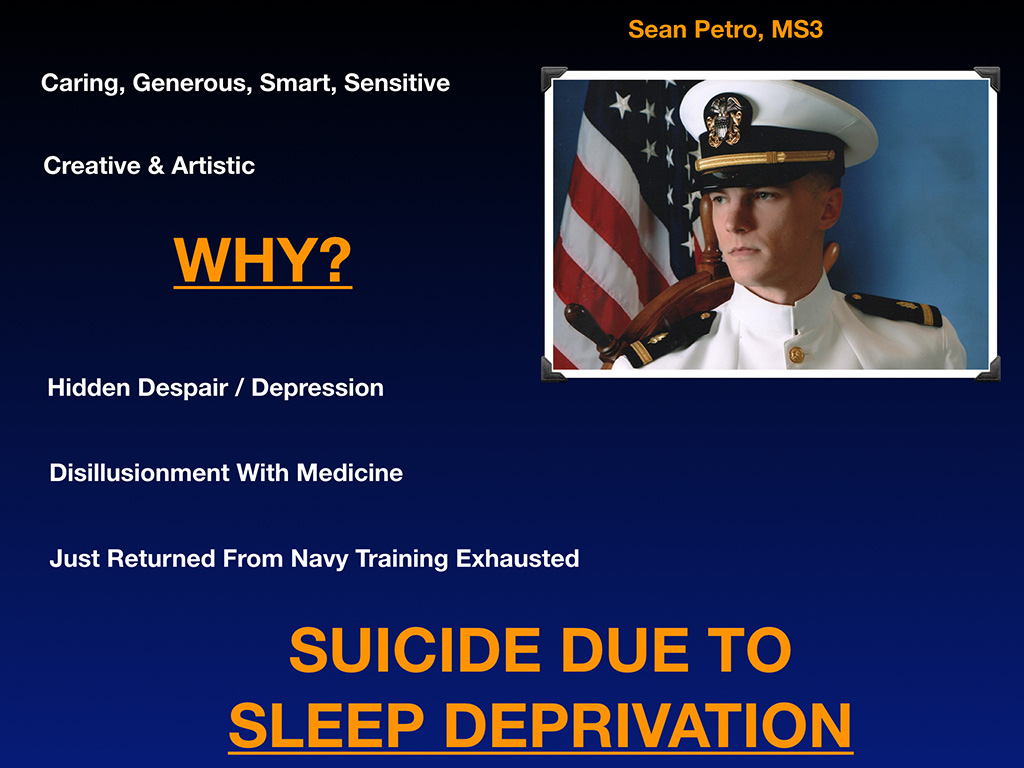

Sean Petro, a third-year medical student. Caring, generous, smart, sensitive guy. Creative, artistic. Must be challenging to be creative and artistic when you’re on a military scholarship in medical school. He’s not somebody who I think would thrive in the military; however, he signed on to the Navy to cover his student debt. He had hidden despair and depression I think earlier in life because his father died when he was a teenager. He then became the man of the family. He was an only child.

You know how painful it is to be on the phone with his mother who lost her only child to suicide in medical school and didn’t see it coming the day after Mother’s Day? Depressing beyond words to lose your only child who had so much promise. His mom believes he had some disillusionment with medicine and he had just returned from Navy training exhausted. Plus he had the usual stressors of medical school, but then you are having to fly across country for additional military training. It probably doesn’t make you feel very creative and artistic or nurtured. He probably could have used a supportive and loving male mentor in medicine himself. He died of by exhaustion and sleep deprivation due to endless demands made on him without adequate support in his training. He saw no way out and hanged himself in a closet.

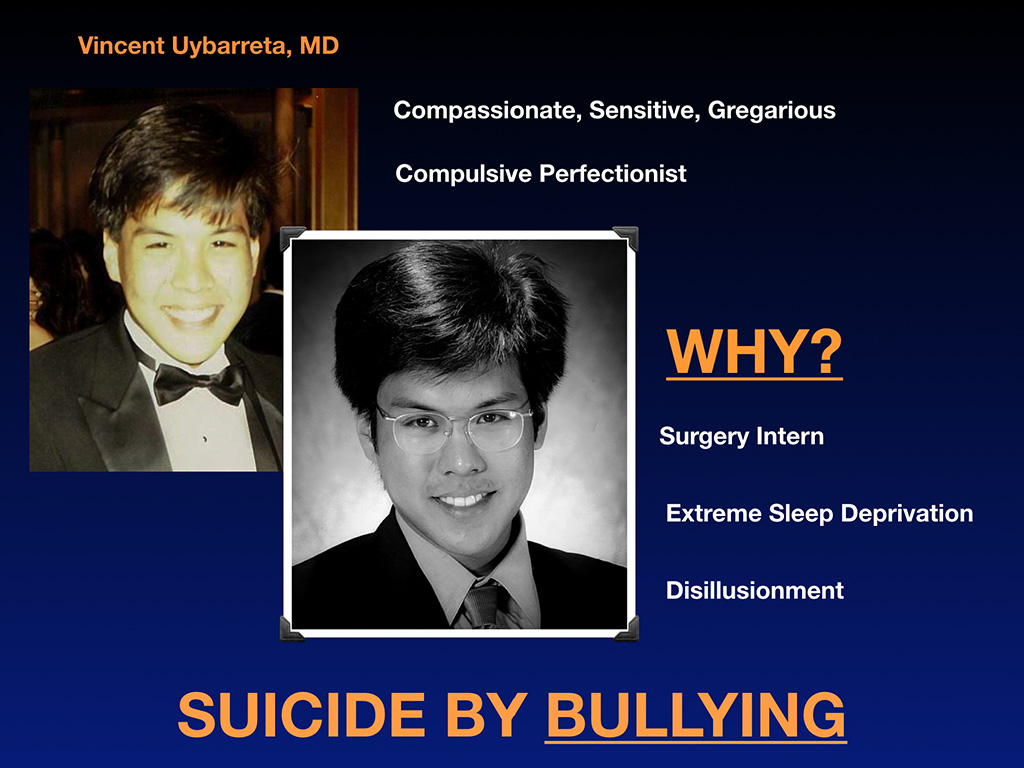

Dr. Vincent Uybaretta. He’s a compassionate, sensitive, gregarious guy. You can tell. This is his high school prom picture. He’s also a compulsive perfectionist. Here he is right before his suicide. Look at his eyes. Look at the difference in his eyes between when he finished high school and his graduation from medical school. Why did he die? He was a surgery intern. Exhausted. The way surgeons sometimes treat each other in training is really sad. Pimping and public humiliation and calling colleagues idiots and throwing scalpels. He had extreme sleep deprivation, lost a lot of weight, was depressed, was disillusioned and he died by bullying and died specifically by hanging in his closet (like Sean), Again, totally preventable.

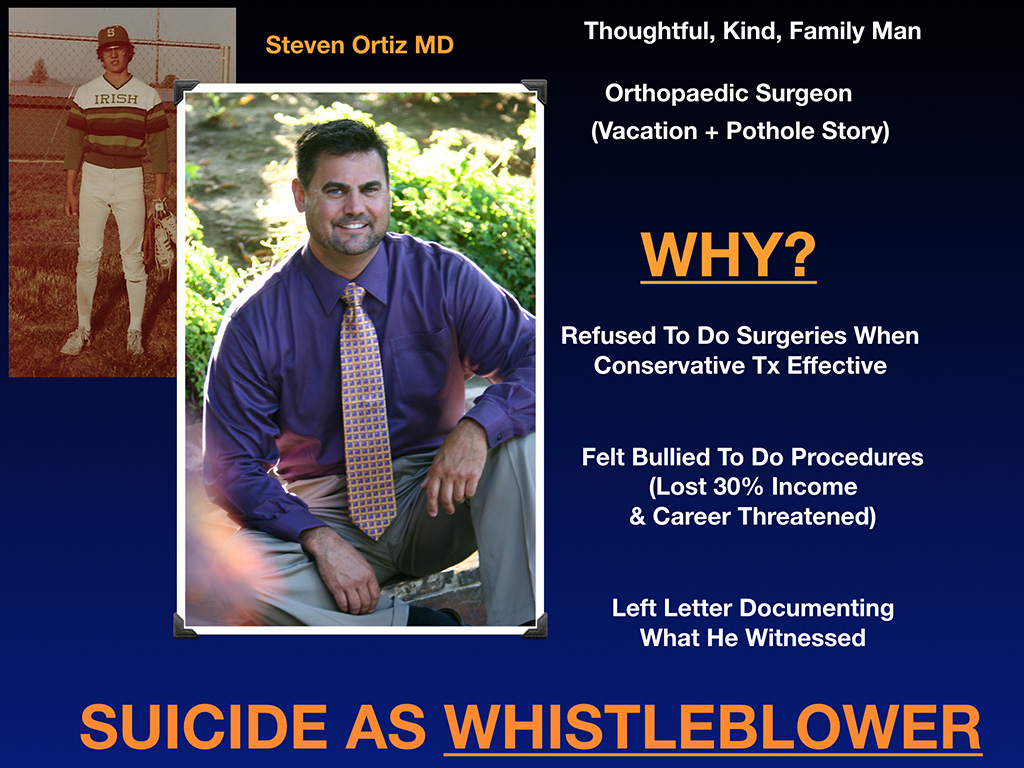

Dr. Steven Ortiz. I absolutely love this dude. He grew up in Eugene where I live. Here’s a picture of him on Sheldon High School’s baseball team. I’m very close to his mom now, so we’ve talked about Steve endlessly on the phone. He died last year. He’s a thoughtful, kind, family man. An orthopedic surgeon. I just want to share with you he’s the type of guy that when a patient fell ill, he came home from vacation early to care for her. I’ve never done that and I consider myself pretty altruistic. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never come home early from a vacation to take care of a patient. This is the kind of guy Steve is.

Now the pothole story. He’s a spine surgeon. He’s working at a hospital where the hospital parking lot has all these deep potholes that staff were complaining of. I’m sure spine surgery patients don’t like bouncing over them either. Hospital wouldn’t repair the potholes. Previously Steve had a career in construction but then got a full ride through Stanford into medical school. He’s a brilliant guy. He actually came to work early one day with cement, gravel, and was out fixing potholes in the hospital parking lot before doing surgeries in the morning. This is the type of guy he is. His mom says, “He’s got 19 years of medical training and he’s out in the hospital parking lot fixing potholes.”

So why did he die by suicide? He refused to do surgeries when conservative treatment was more effective. I think many people in medicine feel pressure to do procedures to generate revenue to keep large organizations afloat through billing insurance for high-ticket items. I know this doesn’t come as a shock. He felt bullied to do procedures which he felt were unethical and lost as a result 30% of his income and had his career threatened. This was not the first hospital where this happened. This is in Florida where there’s a lot of elderly people who are getting a lot of orthopedic surgeries that he feels could be handled in nonsurgical ways. I think he was just exhausted by the fact that even if he moved to another hospital, he wouldn’t be guaranteed it would be different there. This is part of a larger toxic medical culture adversely impacting us all. He left a letter documenting exactly what he witnessed and naming patient cases. Called his mother the night before. She had no idea any of this was happening until that last phone call.

He tucked in his patients in at 2:00 in the morning to make sure they were safe and properly cared for. Doctor suicide victims are often very ethical workaholics until their last breath. They’re checking on their patients knowing they’re going to die by suicide in an hour. They’re checking critical lab results and completing chart notes in the moments before they die. They’re making sure they give the right orders to the nurses. Leaving thank you notes to staff.

Then Steve heads out to the parking lot by the pothole that he fixed, sits down in his truck and and he shoots himself in the heart. He died as a whistleblower. He didn’t feel like he had support. He tried to share his struggles with peers experiencing the same sort of pressures, but I think they told him to “go with the flow.” He felt very isolated and alone.

Several of these suicides on my registry are related to the toxic medical system and are what I call “statement suicides.” The victims are making a statement about an unethical medical system by way of their suicides. They seem to believe that finally someone will pay attention and do something to stop the abuse and criminal activity that they’ve witnessed.

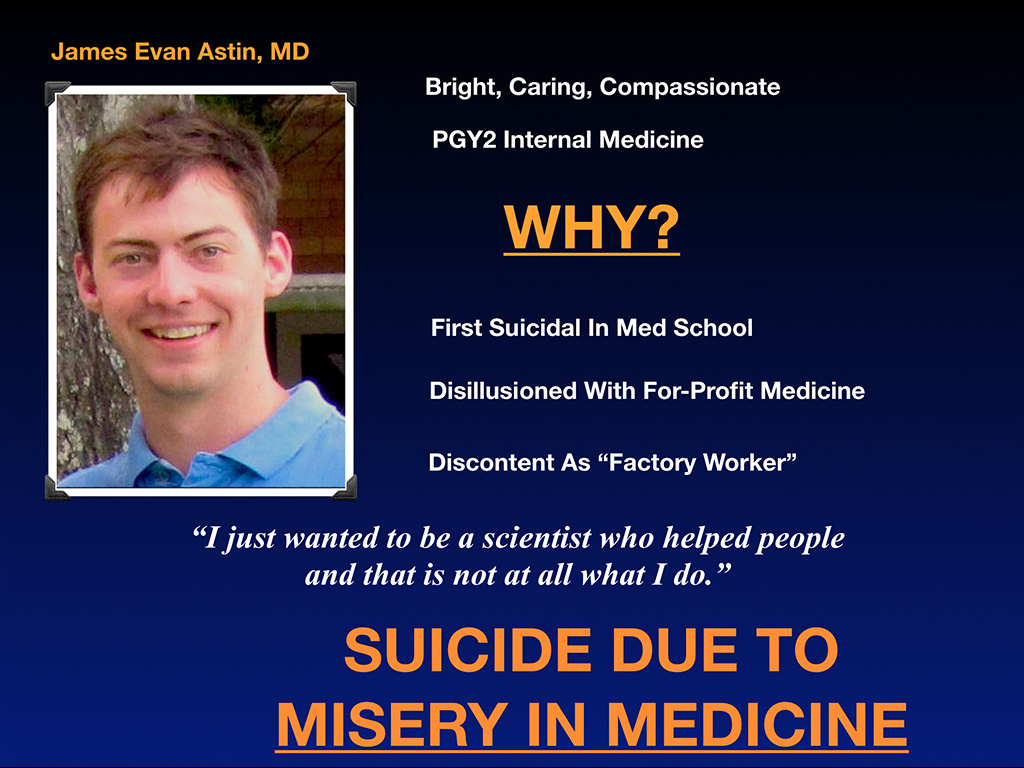

Dr. James Evan Astin. Bright, caring, compassionate second-year internal medicine resident. Why did he die? He first felt suicidal in medical school. He made that clear in his suicide note. He was disillusioned with for-profit medicine, discontent as a factory worker, which is kind of how I felt when I was suicidal. He wrote in a suicide note, “I just wanted to be a scientist who helped people and that is not at all what I do.” He died due to misery in medicine feeling like he was in the wrong career—a career that had been degraded in such a way that he could no longer actually help patients. He was unwilling to participate any longer and could see no other way out.

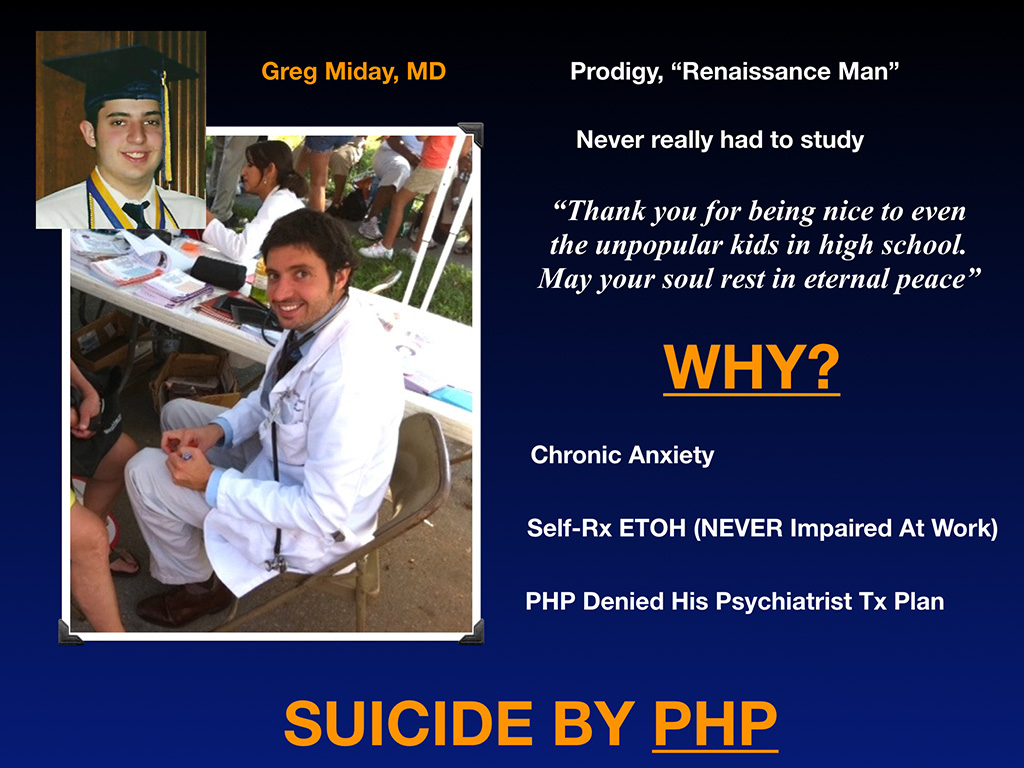

Dr. Greg Miday is one of my favorite people on Earth. His mother (a psychiatrist) schooled me on why not to use the “committed suicide” term. I’m very close to his mom. I’m closer to his family than any of these other families in here. In fact, his suicide letter is on the cover of my book and his mother writes on the back of cover, “In medicine we measure everything except the lives lost from medical education and practice.”

Greg is a prodigy, a renaissance man. Unlike many people (like me) who have to study all the time just to pass classes in med school, Greg never really had to study and seemed to have all the free time in the world to devote to others. On his legacy page online I read this, “Thank you for being nice to even the unpopular kids in high school. May your soul rest in eternal peace.”(you know you’ve got an awesome doctor when years after his suicide patients are still thanking him for saving their lives and not calling off their husband’s code so the family could have a few more years with him). He’s totally for the underdog. Since life was so easy for him academically, he spent most of his time helping other students pass their tests and saving patients lives seemingly effortlessly!

So why did Greg die by suicide? He had chronic anxiety. He self-treated with alcohol, was never impaired at work, was excellent as a physician. In fact, work was a coping strategy that allowed him to avoid drinking. He did really well with patients. He shined at work and he would never drink at work. He’d drink on vacation or to feel normal in social situations. He ended up in the PHP because these hospitals will mandate when they find out that you drink excessively (even on your own time). Greg said if he went into banking or real estate, he would have never been turned in anywhere for drinking on his own time. But as a physician drinking too much on weekends he got locked into a PHP. They sent him way out of town to a three-month program. He was off cycle in his training after that. PHPs mandate 12-step programs and monitoring of your random urine tests for up to five years. Physicians are blackmailed to comply by having their license held in the wings. There is often no physician oversight in these programs!

What killed Greg actually is the PHP. They would not allow him to follow his safety plan designed by his personal psychiatrist. He had already done a three-month PHP stint which one point just by the way, he wanted to call his mom and check in with her. His therapist there at the PHP said, “Oh, you want to call your Mommy?” and just belittling this very brilliant prodigy. It doesn’t really work when lower-IQ folks (non-physicians) are managing high-IQ docs using bullying tactics which is what seems to happen at some of these punitive PHPs.

The other thing about the PHP is it’s a one-size-fits-all 12-step program. Many docs have called to tell me, “I got sent to the PHP for depression and they put me on a 12-step program even though I never drank and I’ve never done drugs in my life. Now I have five years of urine screens that I have to do at my own expense. I don’t understand why I’m in this.” Shocking to me that we’re sending people who have occupationally-induced anxiety or depression or PTSD (with no substance use) into 12-step programs. Some of these physicians are atheists and “giving your power up to God” is not a strategy that even works for them. They’re not a “leave it up to God” group. They’re science-based. Again, not how we approach diabetes. In medicine we use science to create treatment plans that will actually be effective.

Mismanaged physician health programs are leading to loss of our physicians like Greg. Misleading title too leads you to suspect it’s a place you could go for “physician health.” Greg died by suicide because the PHP overrode his personal psychiatrist’s treatment plan after a relapse he had on vacation when he had a breakup with a girlfriend. He turned himself into the PHP as part of his monitoring to keep his license. The PHP undermined Greg’s safety plan created by his psychiatrist. Some of these cases feel more like homicides than suicides that require wrongful death lawsuits in my opinion.

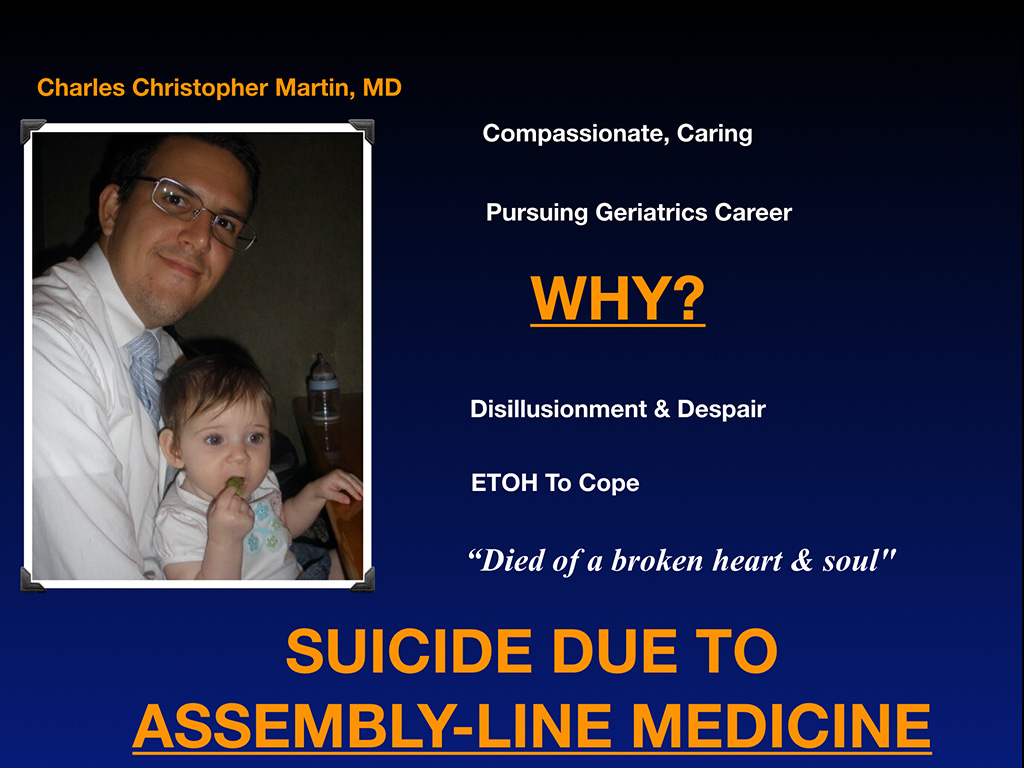

Meet Dr. Charles Christopher Martin. He was compassionate and caring, wanted to pursue a career in geriatrics. Why did he die by suicide? Same sort of thing as some previous victims. Disillusionment and despair with medicine. He wanted to do geriatrics and churning elderly patients through seven-minute visits while maximizing billing codes was not the future he wanted for himself. He used alcohol to cope with his professional disillusionment. He would have been a great geriatrician, but not when trained to be a factory worker. His mom claims he died of a broken heart and soul. I happen to concur. He died due to assembly-line medicine. Had I died by suicide, this would have been my slide (minus the alcohol). Assembly-line medicine killed my desire to live back in 20004 so I can totally relate to his situation.

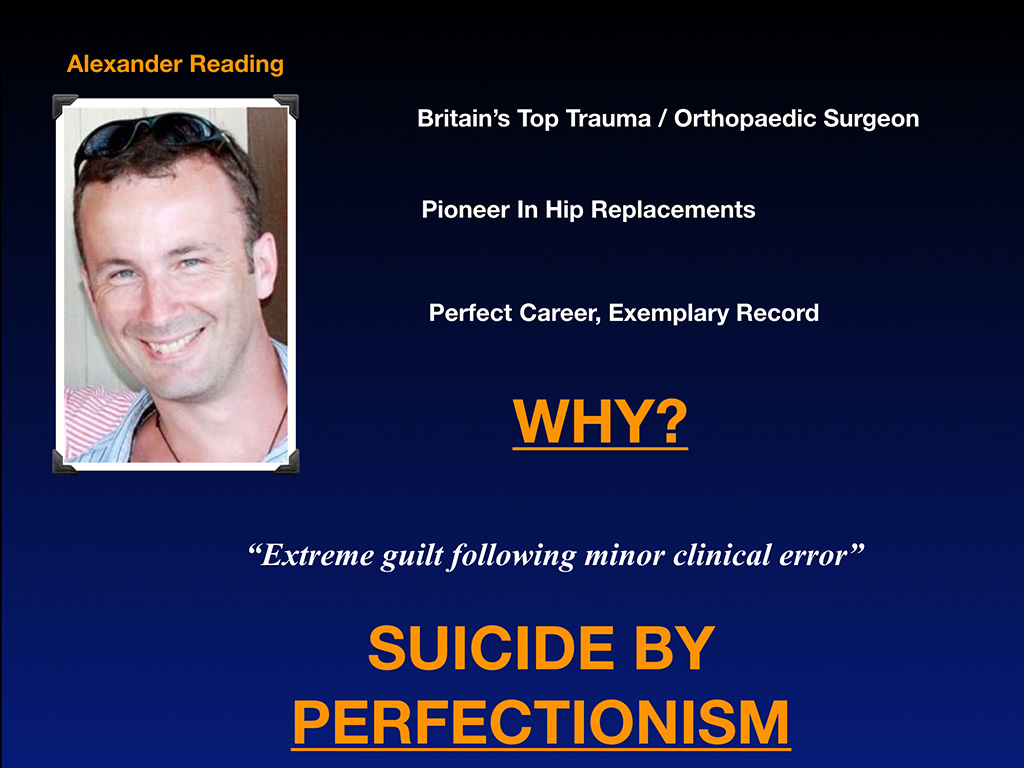

Alexander Reading was Britain’s top trauma and orthopedic surgeon, a pioneer in hip replacements. Perfect career, exemplary record. Why did he die? Extreme guilt following a minor clinical error that did not kill a patient. Really I don’t even think the patient knew they were harmed.

The problem with perfectionists who don’t want to make any errors is they don’t allow themselves to be human. There’s an array of non-malicious errors that can happen when you’re human. For physicians they range from minor to malpractice. Patients may have no idea that there was a mistake or patients may want to sue you. Along that whole continuum, there’s this self-loathing that develops in the perfectioist who made the mistake even if nobody else knows.

I had a doc just tell me the he blames himself for a patient’s death. So he kept the patient’s chart in his bedroom closet for 4 years during residency to remind himself that he is not as smart as he thinks he is. Is that how we should handle these cases? Self-blame and then isolation? Or should we go to therapy and debrief after such incidents? Should we be holding the charts of people that we feel like we’ve somehow injured in training under our pillow at night while we sleep? Not healthy folks. We need debriefing. He died by perfectionism. Analyzing the last thing that pushed these people over the edge, these are all preventable. Perfectionism is treatable so is loneliness and so is depression.

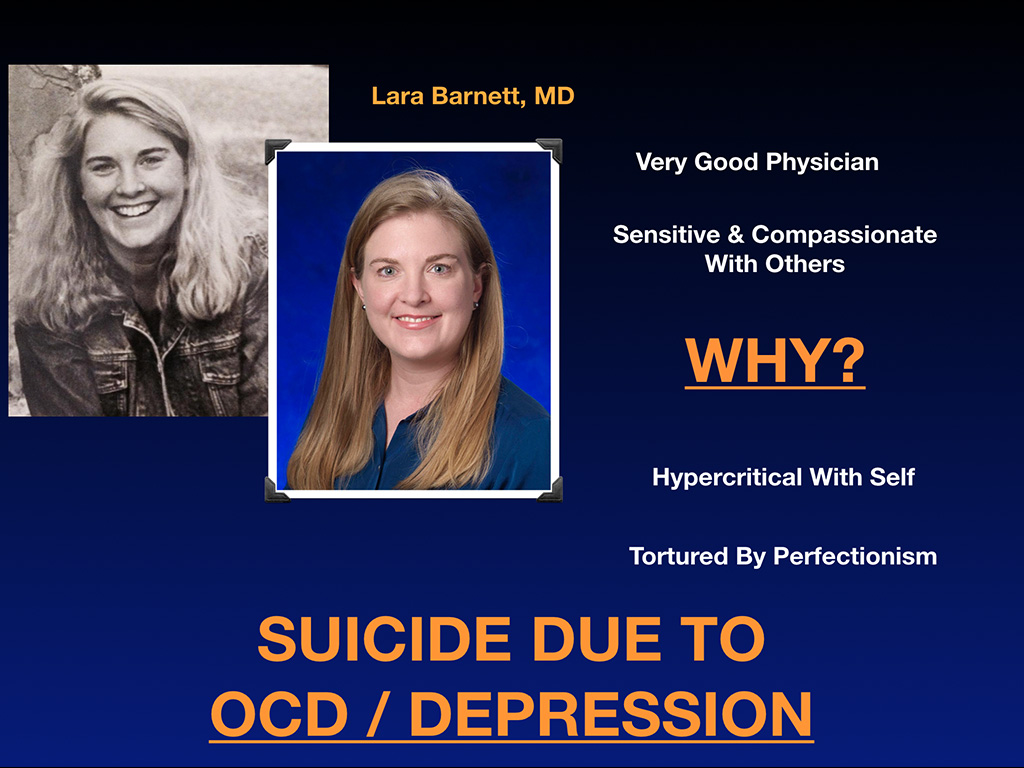

Dr. Lara Barnett was a very good physician. She was an internal medicine resident when she died, sensitive and compassionate with others. Why? She was hypercritical with herself. Any sort of criticism she got, she was fixated on it. Attendings can make offhanded comments that stick with you forever. “Am I an idiot? Should I be a doctor? Do I not understand the renal system?” These sorts of things, they just don’t go away. You get tortured by perfectionism. She died by OCD and depression.

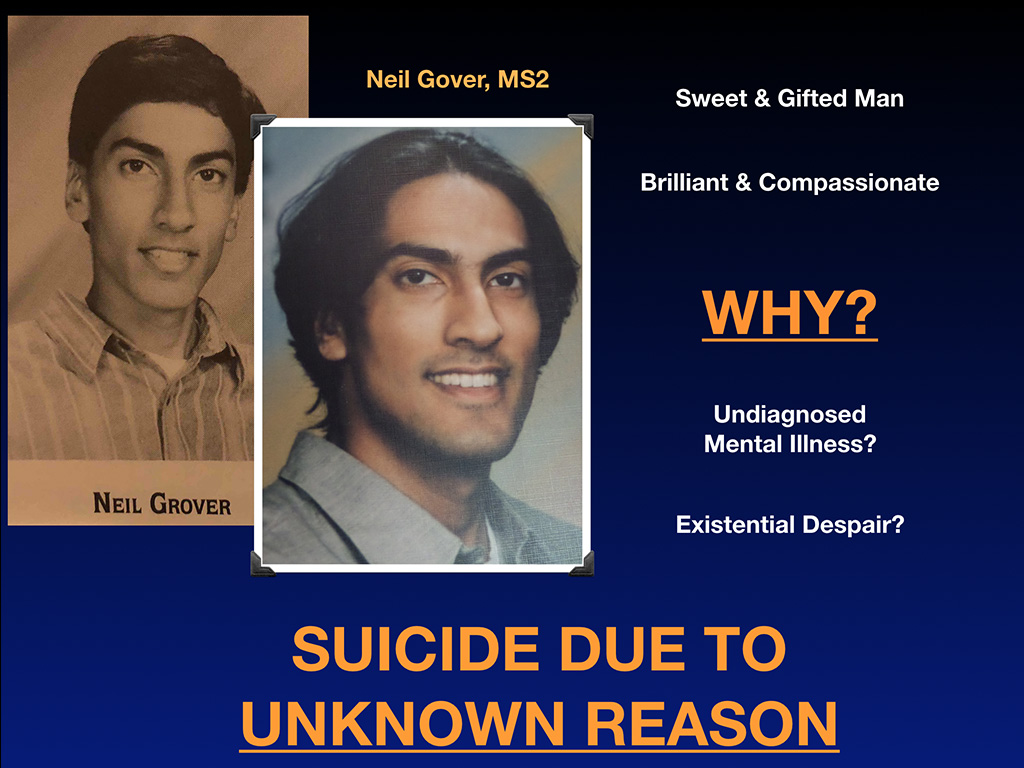

Finally, Neil Grover, a second-year medical student who died 20 years ago. I met with his family recently. What’s so sad is the family still doesn’t understand why he died by suicide decades later. A sweet, gifted man. Brilliant and compassionate. Why did he die? Maybe it was undiagnosed mental illness. Maybe existential despair. At the time he died, he had just ended a relationship with a girlfriend and was reading The House of God. Maybe he was disillusioned with his chosen career. We have no idea. Suicide due to an unknown reason. Many physicians and medical students end up in this category. Why don’t we know? Why are so many people dying by suicide of unknown reasons when they’re surrounded by scientists in top-tier medical centers? Big red flag here that we’re not investigating these deaths. And so the epidemic continues.

As I mentioned earlier when parents send their children off to medical school, they feel their children are in the safest place possible. If they break an ankle or have a medical emergency, they’re surrounded by hundreds of doctors so they’ll get the care they need right away. They have no idea the mental health landmine that they’ve sent their children into. It’s worse than sending them to Afghanistan or Iraq. We have a higher rate of suicide than veterans in the military, but parents and families have had no idea.

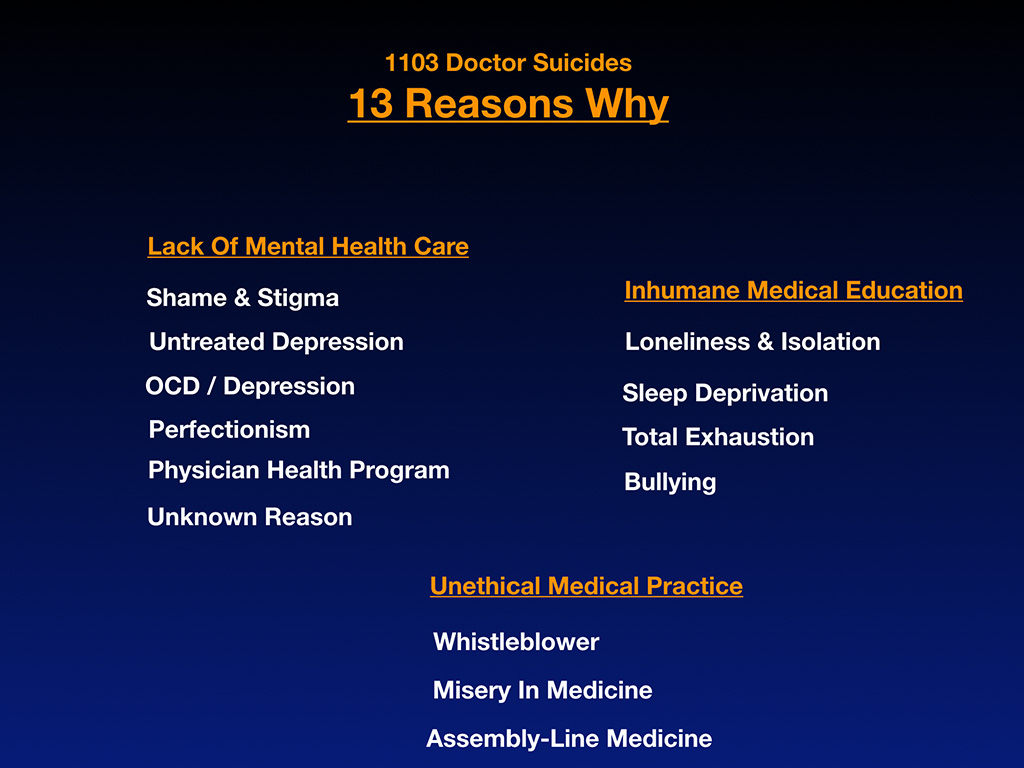

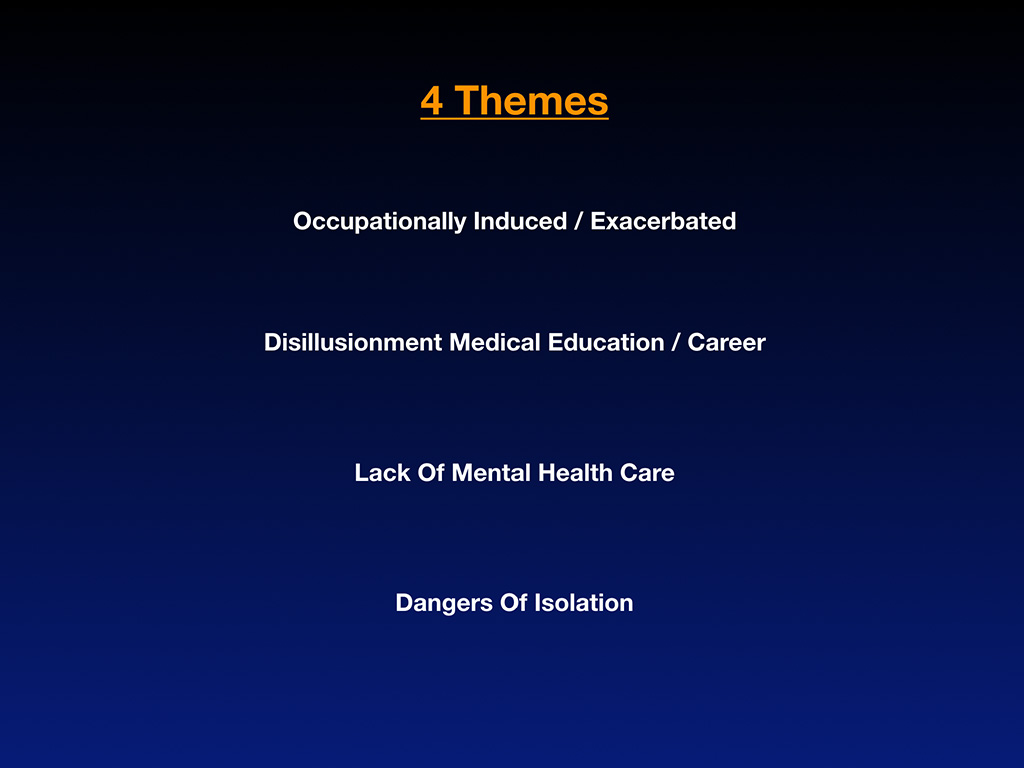

So 13 reasons why just to review on these 1103 cases—shame and stigma, loneliness and isolation. Again, this is all preventable. Untreated depression, total exhaustion, sleep deprivation, bullying, whistleblowing, misery in medicine, assembly-line medicine, physician health programs, perfectionism, OCD depression, and unknown reason. I took these 13 and organized them into thematic categories. The next two slides are my two attempts to categorize them.

First is clearly a lack of mental health care. So grouped here is shame and stigma, untreated depression, OCD depression, perfectionism, which is a mental health issue very unique to physicians and some other professions. Physician health program (12-step programs for everyone is just outright dangerous), unknown reason (often undiagnosed mental health issues). Inhumane medical education is another category where you’ve got loneliness, isolation, sleep deprivation, total exhaustion, and bullying for no good educational reason. This does not improve your ability to deliver health care by being terrorized during medical training. That’s not a good teaching strategy. Unethical medical practices. Whistleblowers, misery in medicine, assembly-line medicine. I think a lot of us feel distraught about the practice of medicine. We have the brain power to solve this if we just would talk about it.

Another way of looking at this 13 reasons is from the human rights violation standpoint which would include sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation is used during war as a torture technique by the military to try to extract information from people. During medical education and residency, for example, we know we’re in a first-world country in a top-tier hospital intellectually. Our body on the other hand is having the same physiologic response it would have as a prisoner of war or in a life-threatening environment—a fight-or-flight survival reaction. Very conflicted and dissociative way to live for 7+ years of medical training.

Human rights violations in medicine include sleep deprivation (and others not on the list of 13 such as sexual harassment, food/water restriction) plus loneliness, isolation, total exhaustion, bullying. Medicine has a bullying culture that is unfortunately widespread. Then of course the other obvious category is lack of mental health care. Untreated depression, shame and stigma, perfectionism, OCD.

Another category I added is lack of curiosity. Really odd that as scientists we’re allowing so many of our colleagues to die by unknown reasons and then just going on with our day after maybe a brief email from the head of the hospital: “Sad to say we’ve ‘suddenly’ lost a colleague.” When we don’t have an M&M conference, we don’t investigate these suicides like we would a patient death, how will we know why doctors are dying?

Four big themes here in conclusion. Doctor suicides are occupationally-induced or exacerbated. They are linked to disillusionment with medical education and career. Suicides are increased among doctors due to lack of mental health care and we have a medical culture that leads to isolation which is very dangerous. All of these people at the end of their lives probably felt like I did when I was suicidal. “I’m the only one that’s a whistleblower. I’m the only one that’s so lonely. I’m the only one with this chronic anxiety.“

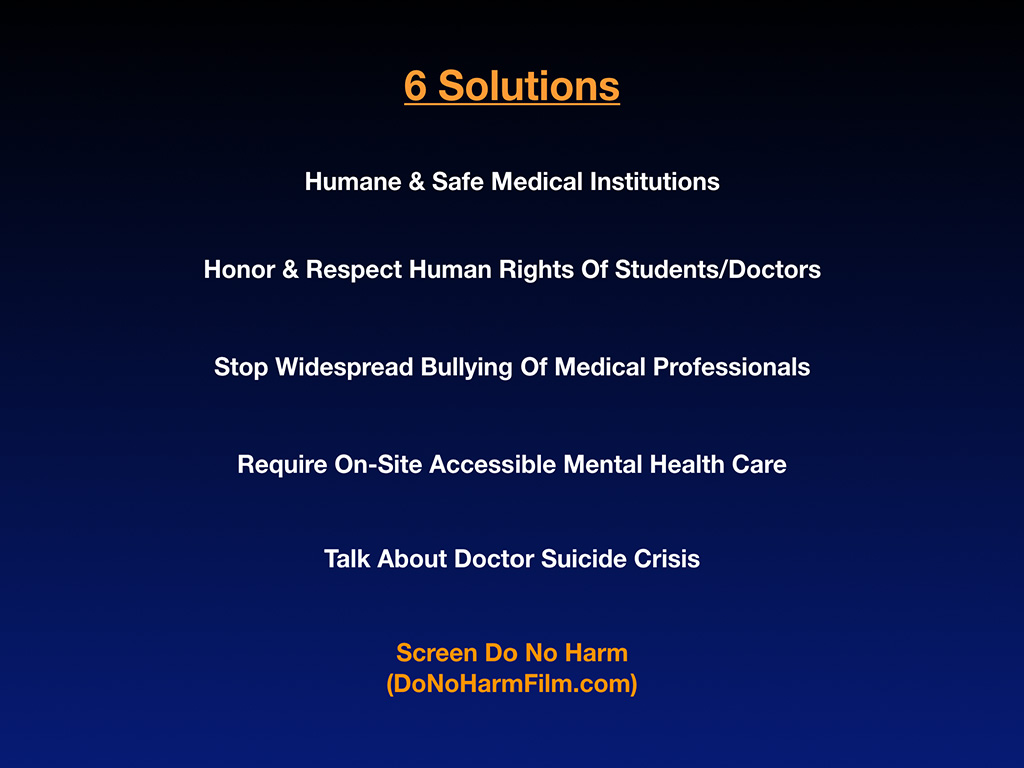

Here are six very simple solutions. Humane and safe medical institutions. Hospitals must be safe zones for patients and health care workers. If you see somebody pimping somebody else, please intervene. Honoring and respecting the human rights of each other would go a long way. Stop the widespread bullying of medical professionals. Require on-site accessible mental healthcare so that when people do need something, they feel safe to go access services during working hours.

I had a chaplain call to ask me how he could help with doc suicide prevention. The infrastructure exists. Physicians could call the chaplain and sit in a special room to cry after a stillborn. It’s not just the family that’s freaking out after you deliver the bad news and the dead baby to the family that’s been infertile for 10 years. You’re having a reaction too. You should be able to talk to the chaplain and cry without documentation on an electronic medical record and being sent to the medical board or a PHP 12-step program. It makes no sense that you can’t access something like that inside our hospitals.

Please talk about the doctor suicide crisis and screen the film, Do No Harm. It’s hard to talk about suicide. Obviously. It’s been 160 years that we’ve been having a hard time talking about it. When you show a documentary with a follow-up panel discussion with leaders in your hospital system, I think that’s a really good way to start the conversation and manifest culture change. Host a wellness day for everyone. Even nursing staff suffer from mental health impacts of delivering care to people who are seriously ill. EMTs have their own mental health issues with PTSD. Showing this film would be a great way to unite everyone on staff and increase empathy across departments.

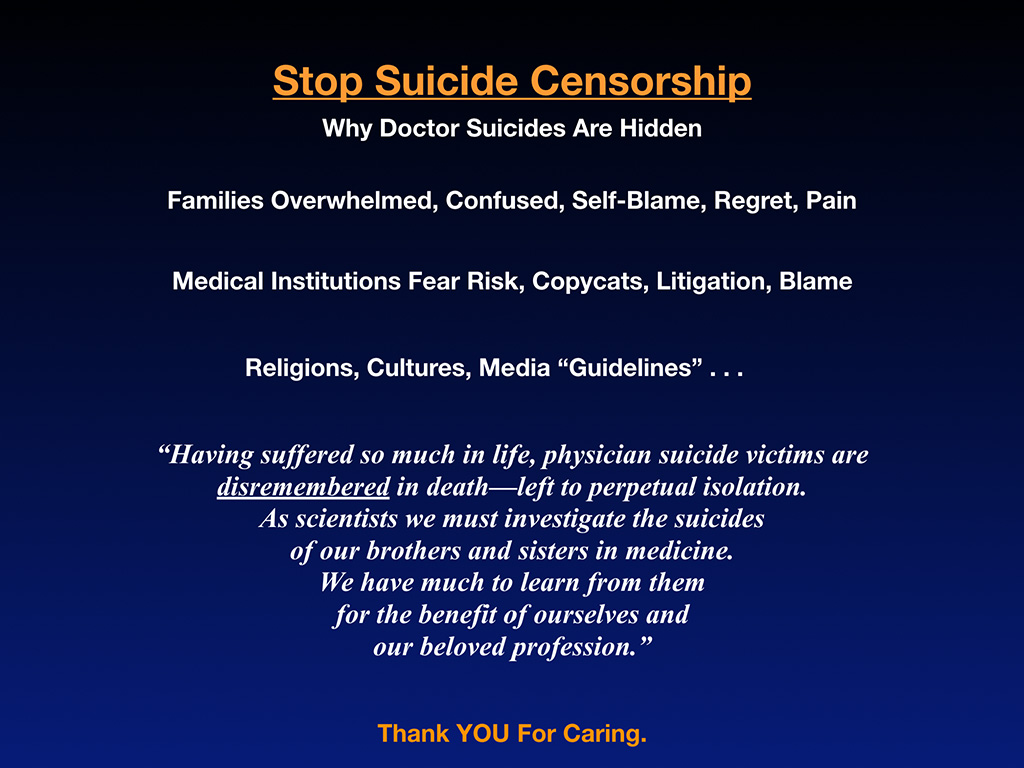

My last plea is to please stop suicide censorship. The reason why doctor suicides have been hidden is that families are overwhelmed, confused, and in sort of a self-blame, regret, pain mode after suddenly losing their star child or husband to suicide. Medical institutions fear risk, copycats, litigation, and blame from this. Religions and cultures don’t help when they suggest everyone’s burning in hell now if they choose suicide and media guidelines censor suicide (while we have headlines about kidnapping, rape, and everything else plastered across the media).

I’ve had my share of emails from the “media guideline police” suggesting I’m sensationalizing and using wrong headlines in my articles. Censoring and not talking about doctor suicide for 160 years hasn’t helped us so I feel compelled to tell the truth. Censorship and secrecy has perpetuated doctor suicides. I’m reporting on doctor suicides from a place of love for my brothers and sisters in medicine (and I’m available for those who need to talk and can refer those suffering to additional resources).

The other media “guideline” that simply does not work so well for doctors is the mandatory listing of the national suicide hotline number. I’ve never met a doctor who has called a generic suicide hotline. Doctors want to talk to other doctors who’ve survived suicide and depression and PTSD. They don’t want to call a suicide hotline and talk to a random college student who has never been to medical school. Someone recently told me he did call the suicide hotline and was on hold for like an hour. That’s obviously not going to work out well either.

As scientists, if we can’t tell the truth, we’re unlikely to solve a medical crisis. If we have untreated PTSD, how can we help veterans with PTSD. We can’t give the care that we’ve never received. Having suffered so much in life, physician suicide victims are dis-remembered in death, left to perpetual isolation. Had I not dug up these cases and put their pictures across the wall in my house, many of these people would be lost to eternity. I just happened to take an interest and talked to their families who were so happy to keep their memories alive. Talking to Greg Miday’s and Sean Petro’s mom keeps their children alive because I’m taking an active interest in them—and now you are too. As scientists, we must investigate the suicides of our brothers and sisters in medicine. We have much to learn from them for the benefit of ourselves and our beloved profession. Thank you for caring.

I’ll repeat questions submitted from audience and answer as many as I can.

Question: Great presentation. I commend you for what you are doing to put the word out. How does the physician suicide rate compare to the general population?

Answer: Doctors die by suicide at two to three times the rate of the general population. We are two to three times more likely to die by suicide than our own patients.

Question: You mentioned physician suicide rates compared to the general population. What about compared to other professions such as law?

Answer: I don’t have the answer compared specifically to other professions. I do know police, firefighters, there are certain professions that have serious mental health impacts just on the job. We should have accessible mental health care for all high-risk professions.

I’d love to have more data (while hoping for fewer suicides). I asked the Oregon Medical Board to start collecting at least the number of doctor suicides in Oregon. They were totally resistant, did not want to do that. I’ve asked them twice. They’re in the perfect position to be able to determine why an active license lapsed or went inactive and the reason why could be suicide or heart attack or moved out of state. They could figure that out.

Now what are we doing for mental health maintenance in high-risk professions? Not much. I know this isn’t really answering your question, but I thought it was a good way to frame our mental health needs so people can understand. Your car is on a maintenance program for its health. Your teeth are on a maintenance program. If you’re over 50, you’re probably getting colonoscopies at intervals. You don’t have to hide, pay cash, and sneak out of town for your colonoscopy. You can just turn around and bend towards this guy and he’ll do it. Why are we not doing the same for our mental health?

Question: Actually, I’ve had this conversation with people in police locally. They do actually have maintenance programs for mental health. They’re actually, when I described the situation in medicine, they said, “Oh wow, we were like this about 20 years ago.”

Answer: So my question to you all is why as medical professionals are we 20 years behind the police in dealing with our own mental health? Shouldn’t physicians lead so we can set the standard for every other profession on this? Shouldn’t the department of psychiatry be the leader on physician mental health and not trailing 20 years behind the police department?

Question: I’m wondering about the gender breakdown. I noticed that most of the stories were male.

Answer: Yeah. Most are male. Of 1103 cases for every female that we lose to suicide in medical school and beyond, we lose four men. It’s skewed towards men. Most practicing physicians are still male, so it’s going to be skewed towards men just because we are still a male-dominated profession. Example, orthopedic surgeons, 92% of them are male. I was the only female speaking at the conference. Obviously, every single one of those 33 cases of orthopedic surgeons featured in my keynote were all male. I don’t have any female orthopedic surgeons who died by suicide. But coming into medical school now, it’s majority female or at least half and half depending on the school so there will be more female cases over time.

Question: What about the relationship between the Oregon Medical Board publications, physician shaming and doctor suicide?

Answer: Every quarter all physicians get a hard copy in their mailbox. I open this thing up and I’m still in disbelief seeing the printed list of all the doctors who are in trouble with the board and details of their cases. Publicly shaming physicians seems to be an invasion of privacy. When published online these details lives on forever. One physician contacted me after a divorce to share that a woman he tried to go on a date with was Googling his name and reading all this stuff from the Oregon Medical Board. How is that going to help you put your life back together? Realtors, pilots aren’t publicly shamed online forever and in front of their peers. I think this is a violation of our civil rights and certainly confidentiality where our private health information is concerned. Apparently doctors and med students aren’t protected by HIPPA.

Question: Thank you very much. This is a really important issue. A couple things. In doing the work and delving as deeply as you have and I’m thinking about a situation that happened last year. A resident died by suicide. There was so much secrecy. It seemed like there was almost immediate censorship. Have you seen a healthier way that organizations for physician suicide have handled this? It seems like it adds a little bit of trauma to everybody else as well not to be able to talk about what happened and what this means and all that. Have you seen a better way of handling suicides?

Answer: So have I seen a better way of handling the what’s called postvention—what to do after a suicide from a medical institution versus censorship, which up to this point is sort of the classic “Let’s cover the tracks and get the blood off the sidewalk and remove the doctor from the website and we’ll pretend like she was never a resident here.” Yeah. Some of these institutions are not only censoring that way, they’re threatening their current house staff by sending social media reminders of never to talk about this or it’s breach of contract and you’ll be fired. It’s not just censorship, it’s active threats against people, many of them J-1 visas who could have their careers destroyed and even be deported.

By not helping the grieving survivors and censoring the suicide that sends another stigmatizing message “I better keep quiet.” People end up with actual PTSD, especially in New York City where a lot of these suicides are very public—stepping off of hospital rooftops. I had a woman call me who was in the middle of a surgical procedure in a patient room and was looking out the window and saw a doctor in a white coat actually actively dying by suicide by stepping off a building. This particular woman started to have flashbacks while doing a procedure. She’s crying because she’s doing the procedure but also witnessing a suicide which she’s hoping is not a friend (but did turn out to be her friend). She’s having flashbacks to three others that she knew that had died by suicide and she just recently graduated medical school less than five years before. Terrible that these people have not received treatment as colleagues afterwards so that they’ve got wounds that are opening and again and again.

Some medical schools are being much more progressive about this. A.T. Still, which is a DO school in Missouri where Kevin Dietl graduated posthumously, his parents are speaking there every year. They planted a tree for him. They have services. They talk about medical student suicide and have quarterly mental health meetings I believe. I’m happy that they’re doing this, however, when we have a public health crisis the CDC should also be involved and we should be tracking body counts (like we would with Ebola or any other crisis). We are making progress. I’m a very optimistic person. A culture change is on the horizon. I’m very glad that you all are here and I’m happy to stay as long as you need me to. I know you have to go back to work. One last question . . .

Question: Do you think gun control would help?

Answer: People in unbearable pain will choose what is most convenient and accessible. Even OTC drugs, car exhaust, a rope, or knife. There’s always something to use for a desperate person who needs to release themselves from pain by ending their life. Overseas doctors aren’t dying by firearms so much. In India, they’re hanging from a ceiling fans by saris. In the very rare physician suicide-homicide cases, gun control would prevent a mass casualty event (though doctors are probably the least likely group to instigate a mass casualty event). Of course, mental health care will ultimately help us help people avoid reaching for knives, ropes, and guns. The brain is ultimately the control panel. Let’s help the brain.

In closing for anyone who is suffering, I’m available. Download my free audiobook here (for more discussion of problems & solutions). I’m happy to speak to you via my website here or come on out to the Oregon coast or mountains for one of our physician retreats (scholarships available for med students & residents). Thank you so much for coming!

Have you lost a doctor or med student to suicide? Submit name confidentially to registry here.

For the culmination of 7 years of research into 1,300 doctor suicides, please reference full report in newly-released book that offers easy medicolegal action steps to prevent future suicides here:

I like part of your talk about people not being felt that they are part of the team and living a society where you are in a fear-driven atmosphere that is a competitive one, not a collaborative one. It affects all of us no matter what occupation a person is.

Hi, we have spoken before but you are so busy that I doubt you would remember. I am a retired Orthopaedist who has been suicidal several times during my life. I have always survived by repeat a mantra that: I will only hurt the ones that love me and make glad those that do not. While I have little formal Psych training, I think this formula might be helpful to some others.

I would be happy talk with someone that needs an ear if you think that appropriate.

Dave

Oh Dave thrilled you are still here with us and I do believe survival stories give so much strength to those who are suffering now. Thank you for being so courageous to share your suicidal thoughts online. Powerful mantra.

I ran across this trying to find other health care providers who share my feelings about leaving my profession due to the stress, frustration, burnout, call it what you want. I am a Nurse Practitioner of 30 years practice and finally retiring happy to be done with all of it. I advise others not to join the HC profession. I also have a sister who died by suicide in her (3rd) but repeated 2nd year, first semester on a full scholarship to medical school. I do not know all of the issues but certainly clinical depression, perfectionism and perhaps lack of direction all played a part. I myself could have also been a victim and was suicidal for at least several years but somehow found a way to get past it. I have been miserable for at least 20 years. thank god I can walk away….

Best wishes to you, Chris, and glad to hear that you are bailing out.

I did the same about a year and a half ago, and I still feel like I’m redefining myself. I told Pam in a separate comment that I sometimes feel guilty about leaving medicine (after 30 years, Yikes!), but felt better after reading about a plastic surgeon that wanted to quit and run a chicken restaurant (true story; I’m not making this up).

If I could make one suggestion – if you don’t already have them, get some cats (preferably more than one, so they can keep each other company when you’re not around). They are really wonderful animals; they’re easier to take care of than patients, and much more affectionate.

Cheers,

-Jack

Thank you for writing about this topic. My husband stopped practicing Emergency Medicine. He woke up one morning and nearly killed himself. I intervened in the horrific event, and I helped “stop” it as he had 3 modes of suicide happening at once. He had left the home and I was able to locate him. Now we both realize how depressed he was. I now have PTSD. He was in practice over 20 years. Some of his colleagues know the story. Do any of them reach out? No. So much stigma with mental health in general and perhaps more stigma with professionals such as physicians. I hope my husband eventually chooses to share his story with docs in training and practicing docs. Self-care is essential. My husband’s career is destroyed due to an archaic physician licensing board statute in OH. Those statutes have now been changed (not bc of my husband’s case), but he was punished (license suspended) for being hospitalized. He self-reported. No patients were harmed. No drugs or alcohol. The good news is that he’s alive.

I would love to speak to you and have resources that will help you and your husband. Contact me here.

Pamela Wible, how can you help, with synthetic meds?

WHY NOT just tell them that depression can be helped with minerals and diet.

Minerals like LITHIUM, CHROMIUM, VANADIUM, and fermented vegetables helps your gut process vitamins and minerals so that the body can absorb them more efficiently.

Does anyone know of a doctor who committed suicide due to failing board recertification and losing privileges? The ABIM has placed significant burdens and costs on MDs to recertify.

Pam. You need to specifically add that the American Dream- i.e. work and study hard- is a lie for all licensed professionals. Licensed professionals have no Civil Rights in the U.S. They are mere subjects of the Totalitarian Administrative State, the harbinger of which is the licensing boards. No one elects them. No one can legally get rid of them. And they do not have to answer, beyond mere lip service, to the public or the lawmakers.

Thank you for your extraordinary work in bringing physician and medical student suicide out of the darkness into the light. Does your work include data on suicide in non-white physician and medical student suicide?

yes

I particularly resonated with Kaitlyn Elkins’ story of loneliness… However, I think all suicides have a huge component of loneliness and isolation, which are even possibly the main components.

Loneliness is now the norm in our society and even much of the world. Most people, my guesstimate would be 80%, have NO non-blood related friends. In a well-known friends study, a friend is defined as someone I talk to once a week and see physically at their house, at my house, or out socially once a month for at least 2 years. The study required physical socialization at each house b/c so many people are so dysfunctional in hiding family secrets that they NEVER invite anyone over. I have a doc acquaintance who is a clutterer. They haven’t invited anyone to their house in 10 years because they only have narrow aisles in the rooms of the house. The rest is stuffed to the ceiling with junk! The house might even have qualified for the TV show “Hoarders!” Of course their kids grew up in isolation because they could never invite friends over….This is so dysfunctional and so sad…I suggested Clutterers Anonymous. Naturally they declined… I LOVE anonymous groups! I am agnostic, not a theist nor an atheist. There is no proof of any deities but lack of proof does not mean proof of lack. So I stay in the grey middle like many Native Americans who often called their Higher Power the “Great Mystery” or the “Great Spirit.” I stay away from the extremes and that gives me a rainbow of choices. Anonymous groups are fantastic mainly for the ending of isolation they foster. One isn’t alone anymore with one’s problems, whatever those problems may be……. Being agnostic, I leave all the “god” stuff out of 12-step, of course….Take what helps and leave all the rest. There are now telephone meetings 24/7 for nearly all anonymous groups, which is literally life-saving! It’s free, it’s at the tip of your fingers, and it’s anonymous. No one should die of loneliness anymore, even those in a dog-eat-dog field like our dysfunctional medical system. Those mandated into 12-step are almost never able to take what helps and leave all the rest, but I found 12-step on my own and those groups saved my life because they offer a design for living that works…

Unfortunately, I fall into the 80% of the population with NO friends. I have no physician friends, either, and don’t know any doc who does. I am currently happily family-free, partner-free, child-free, and sex-free. Especially happily sex-free! I’m a happy solo! No one has my back….except me! Sure, I would love to have 2-3 friends, even one friend. I have reached out many, many times for friendship, but no one is emotionally healthy enough to reach back. It takes a LOT of emotional health to reach back…I’m 62 and at that age, humans’ dysfunction is so progressively great, only people with a substantial amount of emotional recovery can reach back… So I’ve abandoned my futile quest for friends and decided to concentrate on improving my emotional independence instead, and if any face to face friends ever appear on the horizon, great! They are the icing on the cake, but I give myself the cake. I treat me well!

Like Kaitlyn, I was also valedictorian of my class, but I was a homely, nerdy brain… I was bullied all during 12 years of schooling, and somewhat bullied in college and med school, and certainly bullied on the job as a physician. Looking back, I should have learned tease-proofing. Tease-proofing involves not caring what others think of me, not reacting to the teasing with fear, and instead confidently responding with a comeback, often a one-liner comeback. Projecting strength and courage is essential. There is no single best way to respond to bullying and sometimes one has to use trial-and-error. To carry out anti-bullying tactics, I needed to realize that what others think of me is none of my business. I simply try to do the next right thing, and as long as I continue to do that, I ignore others’ opinion of me. It means abandoning the desperate need for friends and instead developing my own persona. It means surviving with a less-than-supportive or even no family at all. It can be done! I’m doing it…. You can, too! I needed to teach myself self-confidence. I needed to reach out for help. But if met with rejection, which is what occurred in my case, I needed to reach in for help, to realize that I could survive on my own, without any friends, family, or outside help if need be. The only person I will never leave or lose is me, as long as I stay connected to some spiritual force. (See the book “Homecoming—Reclaiming and Championing Your Inner Child,” by John Bradshaw.) Without a spiritual connection, I may even lose myself—via addictions or dysfunctions. I didn’t learn all of this until long after high school. I also learned to counter-bully. Counter-bullying involves embracing their bullying, magnifying my own counter-bullying, and reflecting the magnified counter-bullying back onto the bullier. Bullying is actually a cry for help. Only emotionally-damaged people bully others they perceive as weaker. Someone comfortable in their own skin has no need to push others down to raise themselves up.

What we cannot give back, we pass on… What we cannot give back to our perpetrators, we pass on to new victims. What we cannot give back to our perpetrators, usually our parents or those in authority, we pass on to new victims, usually our children or those subordinate to us…. This is called the intergenerational transfer of abuse, per the ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) Study by Felitti. I have a disfiguring medical condition and I was/am homely and have always been lonely, so I found it interesting that such a beautiful girl like Kaitlyn Elkins would die of loneliness. Perhaps being homely and ostracized and bullied from the very beginning forces one to either die early on, or stay polyaddicted in multiple addictions/dysfunctions eventually dying prematurely, or figure out how to survive—even thrive–solo….I’m thriving solo! It isn’t ideal, but acceptance of what I cannot change is the answer to this problem. Ideal would be having a supportive family and friends, a situation in this society very few of us actually have. But practice in emotional recovery makes progress! I’ve had lots of emotional recovery: several different anonymous groups for food addiction, co-dependence, battered women, shopping/debting, adult children, intuitive eating, Recovery International, and lots of other sources of help—all to overcome the pain, trauma, and abandonment I experienced as a child. The best definition of addiction: I’ve found is this: addiction is an emotional illness caused by normal reactions to abnormal experiences in childhood carried forward into adulthood and compounded by ongoing adult life stressors.

Emotional recovery from the pain, trauma and abandonment of childhood carried forward into adulthood is essential to avoid suicide and premature death. Over-achievement is ALWAYS a marker of emotional trauma. Healthy children achieve. They have no need to over-achieve, unlike the emotionally damaged kids who become physicians. I cannot properly take care of myself until I’ve made peace with my childhood. I do this by facing it, feeling it, sharing it, and healing it. Then I can let the frozen grief drop away. Of course, it would be better if children weren’t damaged in the first place, then social connections would be much more common, but at least recovery is possible even without them. We need to change our global life outlook from “go forth and overmultiply, have dominion and destroy, and hate your neighbor as you have learned to hate yourself” to the Native American life outlook of “as much as possible, live in harmony with everyone and everything.” The entire field of medicine follows the first dysfunctional method, as does the entire planet. It’s a dysfunctional design for living that doesn’t work! No wonder docs are a mess and the planet is being destroyed by humans! In the meantime, at least recovery is possible…one day at a time…for me and for anyone who chooses to trudge the happy road of recovery with me… Just pick up your phone and dial in! Get help. Take what helps you, and leave all the rest! You never need to be completely alone again….There will always be a few people searching for recovery just like you….They won’t be perfect; no one is. But they’ll be there…. And with that little bit of help, you’ll be able to have your own back!

Wow. I’ll be your friend. I am so very sorry you have had no one to rely on but yourself. Good for you for being open and seeking healing.

If what has been done to doctors were done to truck drivers, there would have been blood in the streets long ago. Doctors have become to civilized to deal effectively with this outright attack on their civil rights, their noble profession and their humanity.

A good article but with two fatal flaws. First, you imply that all physicians are “high IQ” and non-physicians are not. You stated one of the primary reasons physicians are killing themselves these days is disillusionment with the medical profession. If physicians are of such “high IQ” as you stated, why isn’t anyone smart enough to address the root cause of the disillusionment? Why do these “high IQ” physicians allow themselves to be manipulated by pharmaceutical cartels and greedy hospital empires? Physicians weren’t killing themselves 100 years ago. Why? What changed? All it would take is one man (or woman) to lead the charge. Of course, that one man or one woman would quickly become a target and their career would come to an abrupt end. The billion dollar medical industry does not tolerate rebels or medical mavericks. Linus Pauling and Abram Hoffer are two easy examples.

The second fatal flaw is your implication that God and science are mutually exclusive. Some of the best scientists and doctors throughout history were Christians. Many of the greatest scientific and medical discoveries were made by Christians. A.E. Wilder-Smith, Walter Reed, Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, Gregor Mendel, George Washington Carver, et al. just to name a few. Where are the Christian doctors and scientists today? Well they are still out there discovering, healing, etc. but were forced underground by Big Medicine, the very same fraternity causing physicians to kill themselves every day in 2019.

1) “First, you imply that all physicians are “high IQ” and non-physicians are not.” Not the case. Obviously others have high IQ. Physicians have stunted emotional IQ and social IQ development often so a mixed bag.

2) “Why isn’t anyone smart enough to address the root cause of the disillusionment?” Umm . . . so that’s what I’ve been doing 24/7 since 2005. I think I’ve made some significant headway as one person 🙂

3) “Why do these “high IQ” physicians allow themselves to be manipulated by pharmaceutical cartels and greedy hospital empires?” Most are controlled by fear and have been heavily indoctrinated (not unique to physicians).

4) “Physicians weren’t killing themselves 100 years ago.” YES they were I have cases on my registry back to the 1880s.

5) “The second fatal flaw is your implication that God and science are mutually exclusive.” How did you come up with that???

~ Pamela

Thinking of dying by your own hand, everytime you reach disperation, is a way to cope with the misery in medical practice.

To die or not to die is a matter of effectiveness.

I found a lot of myself in the stories you presented. Thank you.

Hello Pamela

I admire and respect your work.

I am a psychiatrist from Colombia, South America.

Your quest is both necessary and thoughtful, I would like to start a program in my city (Cali).

I am also a med school teacher and private practitioner (no insurance no intermediaries), not much of consult volume but happy to be of help and familiar with MD mental health issues.

Would you be interested in coming down for a symposia ?

If you are I could start raising funds to host you and organise the meeting.

Over the last 5 years we have had at least one suicide per year both in nurses and physicians, the most recently a female pediatrician in one of my workplaces.

I will be happy to start conversations and exchange of thoughts with you.

Thanks for reading

Yes, absolutely happy to help. Contact me vis my website and I can email you some info. I majored in Spanish in college so I may be able to communicate in your native tongue 🙂

Wow! Dr Brett Gemlick. He really was one of- if not the best – ortho surgeon in this area. Highly regarded. He was number one in his class at Ohio University. He was married to his “high school sweetheart. “

I am still having a rough time wondering what drove this Man to the point of no return? Did he leave a note or anything to offer an explanation? I wish we could know more, to maybe get over this seemingly wonderful Man’s decision to end it all 😔.

Which particular man are you referring to?

I actually have a question. How many states have legal medical policies that disbar medical professionals if they seek mental health treatment, and are life coaches and religious professionals considered mental health professionals in that context? In my mind that is the issue, and I’m being told by a medical professional friend that they will be disbarred if they report even engaging officially with a life coach, because they’re considered counselors.

I would be highly uncomfortable if I thought my medical professionals were suffering from mental health conditions, even if temporary. It makes no sense at all to me that the same professional I’m urged to seek treatment from if I’m feeling anxious, depressed or chronically angry, is forbidden from seeking the same help for THREAT of losing their career. In what situation does that make sense? How can a counselor, psychologist or psychiatrist treat patients if they’re being challenged by the same conditions as their patients? What sense does it make to forbid them from the same help? To me that is blatantly putting their own patients in jeopardy of proper treatment!

Other high stress careers won’t put their professionals who make life and death decisions back out in the field until they undergo counseling after certain situations, so how can that be forbidden for medical professionals?

Doctors have been punished for having to check the “yes” box on state licensing applications that ask about mental health. I’ve just written an article on this topic for a peer-reviewed journal that will be published soon. In the meantime see this: Why doctors don’t seek mental health care.

Excellent doctor presentation, I think it is very valid to deploy this issue of public health in this way. Thank you very much for your commitment to humanity.

Thank you for addressing this! I was in a very innovative medical school program and fortunately made more friends (and this was over 20 years ago.) I was in my mid-thirties, had not majored in science, but once I got to my clinical years, I shone, and did well except for the lack if sleep on my OB/GYN rotation. I had known I wanted to be a psychiatrist since very young. All I can say is what a horror residency was. I had been under excellent treatment by two psychiatrists, consecutively for depression and anxiety, with therapy and meds, since graduating college. Nobody in the psychiatry residency had anything against me about this. However there is so much pressure to be a “strong” resident. And I was. There were a lot of “weak” residents from all years, and only a few of us who kept things running. In all rotations, you suddenly realize that as a resident, you are now making life or death decision. On my first night in residency, on internal medicine, I pronounced 3 people dead and filled out 3 death certificates. They were all terminal, but had not been signed out to me as such! As a “strong” resident, I was asked to do more and more: extra teaching, covering more services, etc. Refusals were not allowed. At one point I was overseeing community medicine for the county with temporary attendings who never showed up, covering the ER and the jail during the day, and evaluating crisis patients, sometimes at their homes! That was during my second year. I got so little sleep during residence. On night float, I couldn’t sleep during the during the day, and I had status migrainosus for 6 weeks. Residency was hell, and contract negotiations should be the rule. Few Americans will even go into psychiatry anymore, and practically none practice therapy. I do both biologic psychiatry and therapy. And btw, I was valedictorian of my high school!

I listened to the entire presentation (shed tears). I feel you are spot on with your recommendations; however, a topic that was not addressed is how do doctors integrate their profession into healthcare without the stigma that you are smarter than everyone else, more educated than everyone else, etc. The speaker kept referring to doctors with those anointed titles. You as a profession are holding each other to a higher standard. As a registered nurse for 35 years and a family nurse practitioner for 21, I feel blessed to be at the “top” of MY career… for you to tout doctors as “gifted” above others… you are feeding into the stresses that you say should not be there! Perhaps, the medical profession can be taught to integrate with the rest of the world. We all need to feel good about our chosen careers. We all need to learn we ARE not Better than others…perhaps than we won’t hold each other to the standards that are killing people… revisit your talk…by saying that doctors are the “gifted ones”, you contribute to the problem.

Thank you for the tremendous effort of collating and sharing the stories of those who have passed before their times.

Personally I struggle with internalised depression myself and am trying to speak up a bit more on it. Like so many in the list I am a high achiever and a respected physician.

Would like to raise a few points of discussion,

I believe we are selectively breeding medicine into oblivion. Most countries, only the best and brightest are chosen to pursue medicine, many of us not by choice but by virtue of being the best and brightest in our respective schools. Culturally in Asia the pressure is higher with certain families pushing their children to the life of medicine.