Attention all doctors: The first three are mine. The rest are from miserable colleagues. All true. And common. If you’re a doctor and you recognize anything on this list, please quit your job.

10. You feel nauseated when you see your clinic logo; you alter your commute to avoid streets with your clinic’s billboard.

9. Discouraged by the general despair among staff, you try to be joyful. Then you’re reprimanded by the clinic manager for being “excessively happy.”

8. You dream of leaving medicine to work as a waitress.

7. You envy your sickest patients and/or you develop a perverse pleasure in your patients’ pain.

6. You pray you will be diagnosed with cancer so you can get some time to sleep.

5. You spend your nights trying to keep patients alive while you imagine ways to die by suicide.

4. You work 16-24-hour shifts and have not had sex with your spouse in months.

3. You’re a top-rated doctor, yet you daydream about walking into traffic, jumping through the window, or just dying in the course of a normal day.

2. You are counting down the days until retirement during patient appointments.

1. You change your computer password to “fuck [name of hospital where you work]!!!”

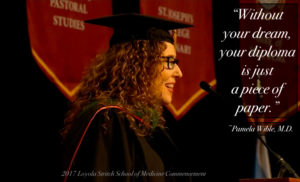

Are you a doc who wants to quit your job? Want to live your dream?

Join the next Live Your Dream Teleseminar—and find out how! (It’s easy!!)

Pamela Wible, M.D., is a family physician and founder of the ideal medical care movement. She was named the 2015 Women Leader in Medicine for her pioneering work. Watch her TEDx talk on ideal care. If you’re a medical student or doctor, join the next teleseminar & retreat so you can learn how to stop suffering and start practicing real medicine. Photo by GeVe.