Note: Thomas Fishler, MD, is correct spelling of his name.

Kick-off keynote delivered on February 7, 2020 at AO North America, an international organization serving veterinarians, craniomaxillofacial, hand, spine, and trauma surgeons.

Introduction: It gives me great honor and privilege to introduce our first keynote speaker for the day, Dr. Pamela Wible. Dr. Wible is a family physician born into a family of physicians. Her parents warned her not to pursue medicine, but she followed her heart only to discover to heal her patients, she had to first heal her profession. So she held town hall meetings and invited her community to design their own ideal clinic. Open since 2005, Dr. Wible’s community clinic has sparked a movement in which patients and physicians are designing ideal clinics nationwide.

When not treating patients, Dr. Wible devotes her life to medical student and physician-suicide prevention. She runs a suicide hotline and hosts retreats with discouraged medical students and physicians, for which TEDMED has named her “The Physicians’ Guardian Angel.” Dr. Wible has personally compiled and investigated more than 1300 doctor suicides, and had analyzed the data for high-risk specialties and actionable solutions to prevent future deaths. Dr. Wible is the author of Physician Suicide Letters-Answered. Her blogs have been picked up by major media, such as The Washington Post and Time Magazine. She has been interviewed by most major TV networks, and is a frequent guest on NPR. She is featured on the documentary Do No Harm, that exposes our hidden physician suicide epidemic. So put your hands together to welcome Dr. Wible to the stage.

Pamela Wible, MD: Thank you so much for having me. I’m really excited to be here. Originally I was on the schedule the last day of your event, and then they moved me up to the middle day and now, with the late-night phone call I got in my hotel room last night, I’m your first speaker, how about that? I got promoted.

So, we’re going to talk about the culture of wellness through a really interesting lens that I feel is not discussed, because it’s a bit of a taboo topic; but it’s going to give you a lot of insight in how to move forward with an actual strategy that will be effective at creating a culture of wellness. So take the journey with me. We’re going to start with physician mental health.

This is a quote that I gave during an interview that got a lot of traction online. Now, in this quote there are two tactics that have been used to deal with the obvious despair that exists within our profession. Meditation/yoga on one side, let’s just kind of sweep this away here and maybe if we just took a nap and a green drink. Then on the other side is early retirement, I’ve got to get out of here. Right? Because I talk to a lot of surgeons and their spouses who tell me that their partner is counting down the days to retirement, trying to make an early exit.

So somewhere between the early exit and meditation is an actual solution—a real strategy. And so we’re going to discuss that today. And I think you’ll find some relief in the fact that I am a truthspeaker, so I don’t hold anything back, but I am delivering this with great love for my profession and to save lives of my colleagues.

So the learning objectives today are to learn a targeted, high-yield set of actions you can implement to promote wellness among physicians today. And this does not require you to sit in committee meetings or get any approval from anyone. You can actually leave this lecture and do it right away, right now, because I’m a very action-oriented person for those of you who have read any of my blogs and know me. Also, we’re going to understand how to create a culture of wellness utilizing a concept I call, “institutional triage,” which I coined just for your conference. And I think you’ll be able to relate to it. And then discover the highest-risk specialties for suicide, and what you can do to stop the crisis.

Now interesting, while I was putting these slides together I actually got this email.

Very interesting that I would get that as I’m loading the slides up. So, I have a question for you. I know you have a little book that you can jot some notes in and I would encourage you to get that out and a pen, and start to contemplate some of these deeper emotional concepts I’m going to bring up. But my first question, which you would know better than me because I didn’t survive a surgical residency, I did family medicine which was awesome in Tucson, Arizona. Great to be home, by the way I’m also a Texan, grew up in Texas.

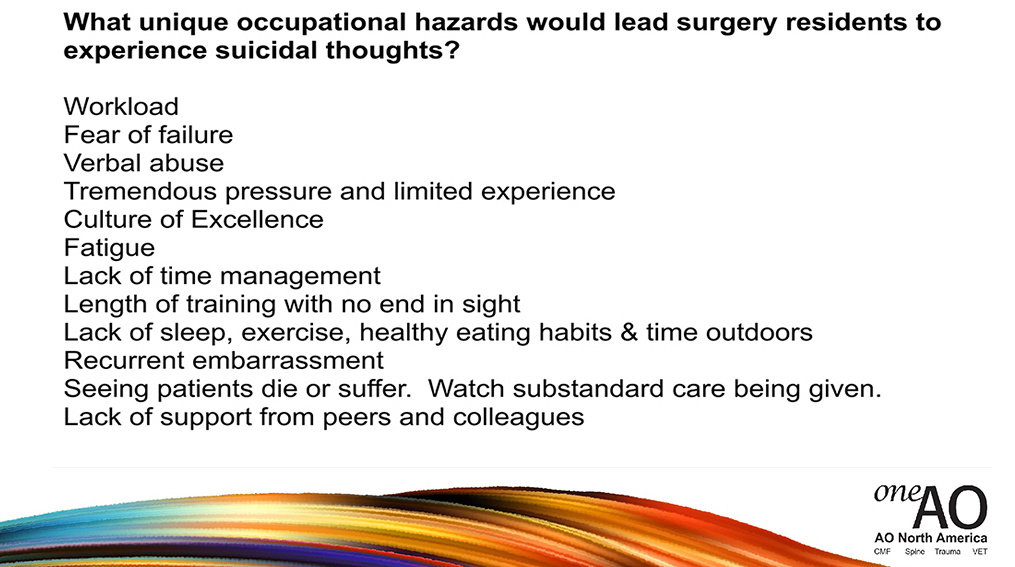

So the question I have is: What unique occupational hazards would lead a surgery resident to experience suicidal thoughts?

And I just want to give you some time to write some things down. One or two thoughts, that’s unique to a surgery resident, or a resident in general. You can write that down privately in your book. You can also use your type pad and submit this so it can be read anonymously, potentially. And then I have a follow-up question, I’ll also give you some time to think about this. Because surgery residents are reaching out to me for help and they’re not reaching out to one another, and not necessarily to you for help, so that’s odd. I’m in Oregon and I’m a family doc, right? So I think you all have a lot of insight on this. I would like you to mine the insight you have on this topic.

And then a second question is: Have you ever known of a medical student or physician who has died by suicide?

And please write that name down to honor this person’s memory. I’m going to let you sit with this for a minute and I’m going to tell you the story of an orthopedic surgeon who died by suicide in my town of Eugene, Oregon.

I have a registry where I collect data and names and investigate these, and try to figure out why these people made this fatal decision. And I had moved to Eugene in ’96, I didn’t really know about this guy until recently. I was trying to figure out okay, wait there’s an orthopedic surgeon from ’96? I thought certainly living in a small town I should be able to track down some people who knew him personally, interview them, find out a little bit more about him. I found myself on the phone with a number of retired orthopedic surgeons, other surgeons in my town, asking them about this particular gentleman. And they said, “Oh he was a tall, friendly guy. Always came to the meetings. We didn’t detect anything. Took us by surprise.” But what was interesting, this gentleman, a retired surgeon, called me the next morning and he said, “Pam, I’ve really been thinking about the conversation we had last night. And I just want to let you know five more names that popped up of doctors in our county that have died by suicide, just to make sure they’re on your list.”

This happens over and over again. I’ll talk to somebody about one suicide, and because I’m so accessible and nonjudgmental, sort of opening a portal into them retrieving material from the past, something that I call suicide amnesia. These suicides are too difficult to think about, so you just pile them into a secret vault. But when somebody then asks you, “tell me about a suicide,” here comes five more. Like “my roommate in medical school. The intern, during my interview there was an intern that just stepped off the roof.” Right? So there are these memories. So I’m encouraging you, right now, to retrieve some of this and at least down the names or “the intern when I started died, I didn’t know her,” that sort of thing.

So, this is the book. It’s the second book that I wrote called Physician Suicide Letters. This is free, a free audiobook if you like the sound of my voice I can lull you to sleep by reading suicide letters by doctors. I know that sounds like a terrible bedtime story, but I want you to know that these are letters from doctors that, by and large, survived their contemplation of suicide. So these are people on the edge who wrote me, kind of going through the pros and cons. “I’m thinking of ending it, but I don’t want to do it for this reason or should I?” They’re actually very insightful into the psychology of the decision-making that goes into whether somebody would end their life as a physician. So I would encourage you, I mean it is on Amazon, but if you want a free copy, there you go. On my website.

Then I want to mention why, I know this sounds very depressing. What a depressing way to start a conference, you start with a suicide speaker. Terrible, right? But I think through this lens we’re going to make the most progress and have a lot of release and relief, and really bond and create the type of conversations that will be so meaningful for the remainder of this event. So this term, institutional triage, is a term I coined because we triage patients who come in, right? If you come in with a mangled lower extremity we’re not going to focus on your cholesterol right now, we’re going to start with Airway, Breathing, Circulation, the major fracture there. So what I’m suggesting we do is apply those same concepts, that you already use as amazing surgeons to save lives, to the institution of medicine. If we prioritize addressing institutional issues such as suicide, I bet downwind from that we will create a culture that’s really well. That has the potential to be well.

So, this is from a chapter in the book.

I really need for people to understand that some of the ways that we’ve trained surgeons, traditionally since 1889, leave lifelong psychological effects in people that are very detrimental. So please, realize your words are very powerful as a mentor; and when you say something like, “I’m proud of you,” that could stick for somebody’s life, and if you say “That was stupid,” that could also stick in somebody’s head and replay over and over again.

I want to share with you the most disturbing sentence that’s ever come to me in an email. Thousands of people who are struggling and suicidal in medicine have written me. This happens to be the most disturbing sentence, which created a lot of profound thinking on my part, but a medical student wrote me and said, “I was less stressed in Afghanistan than medical school.”

I mean that’s pretty traumatic. Felt like I needed to call this woman up and find out what she meant. Why is this? Here’s what she told me, and she’s in active warfare with landmines, sniper fire, I mean how can medical training be worse than that?

And that is really key. There’s a feeling of safety because you have 100% trust in your team. If you’re blown to smithereens by a landmine, you know that your people are going to pick your body parts back up and you’re going to be honored back in America with a flag opening, your parents are going to be there, they’re going to blow the bugle, whatever they do you’re going to have an honorable end and not just be left.

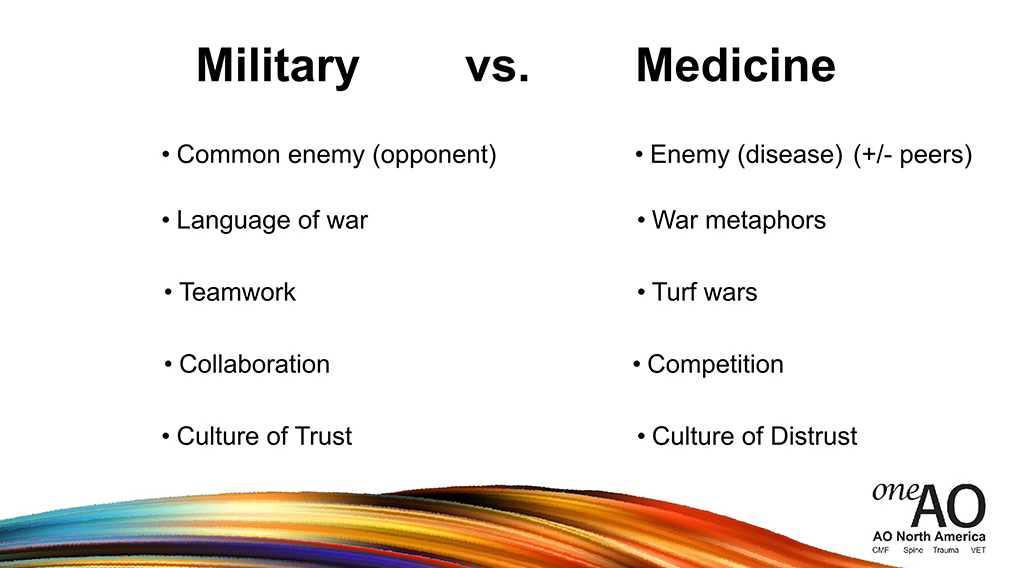

In medicine, because this has unfortunately been set up in a pyramidal structure by William Halsted in 1889 with the first surgical residency, it’s more like a gladiator fight. Who’s going to survive and we’re going to compete against each other. And I think that does long-term psychological damage—that creates terror in people, they have panic attacks, they decompensate and don’t have normal lives afterward. I want to compare the military and medicine in the way that we are with one another.

So in the military there’s a common enemy, everyone knows who it is. It’s the other side and they are wearing different outfits, right? Okay, in medicine there’s the enemy that’s the disease, right? You want to eradicate the disease, fix the fracture, save the patient’s leg. Though also, depending on your residency, the enemy may be your peers. In med school you’re all competing to get into orthopedic surgery residency, so you’ve got to get a higher score than this one. It is a competition against each other. Terrible model of training. Super sensitive people that are humanitarians who want to serve others, to put them in a gladiator fight is not good. Language of war is, obviously, used in the military but you might have noticed that we use war metaphors quite a lot in medicine. I think we should really change that into more compassionate language, for the benefit of everyone. The patient overhearing us, your colleagues, right? Teamwork in military, you know these people have your back. In medicine, it’s about turf wars.

I even have psychiatrists that are upset with me because I’m handling the physician suicide crisis the way I am. They feel somehow threatened, “Why is she doing this? Stay in your lane, you’re family medicine. Do strep throat, UTIs, we’ll handle the doctor suicides.” Well, you’re not making much progress. We’ve known about this since 1858 in the UK, it’s 162 years later. I just decided to take charge. But this sort of physician infighting has caused third parties to come, swoop in, and take over our whole profession. We need to be a solid team to prevent ourselves from being taken advantage of by unsavory forces, MBAs and others. I mean nothing wrong with that, I’m just saying there’s people that have divergent ethics, swooped in to our whole profession and taken charge of us.

Collaboration is key in the military. You certainly are collaborating and you want to save each other’s lives. In medicine, it’s a competition. So in the military there’s a culture of trust. Unfortunately, in medicine there’s a culture of distrust. I think we need to get this head on.

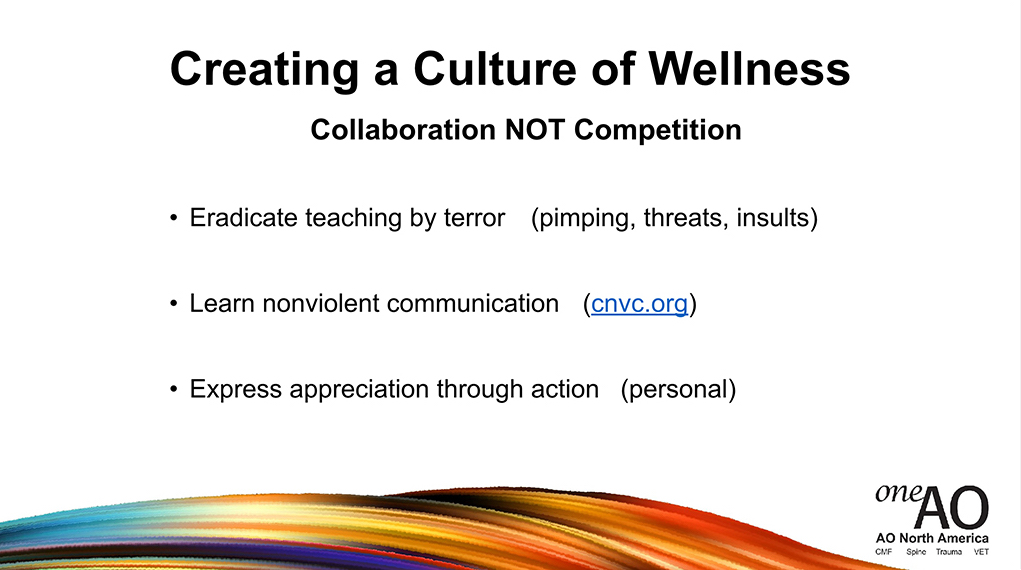

Now to create a culture of wellness, essentially what I’m talking about is that we, beyond lip service, truly collaborate and break out of the competition model. It’s not working. These are some things that I would suggest.

That we eradicate teaching by terror. There’s nothing wrong with pimping if it’s done in a humane way, because you’re really trying to help somebody learn. But malicious pimping, I mean threats and personal insults, that’s terrible, right? There’s an actual communication technique called nonviolent communication. That would be a really cool thing to teach at a conference, or have a one-hour session at your hospital. You can go to CNVC.org. It helps us have a communication style that makes other people feel safe and actually, even better, they’ll be able to hear what you’re saying and not go into an internal panic attack. Since we’re all working for the same cause to save the patient, I think communication is key and having strategies, ways of expressing yourself where you can be heard without scaring the other person, is really important.

And also, expressing appreciation through personal action. Again, this isn’t waiting for a top-down ‘we’re going to be nice on Tuesdays and everyone send love notes to each other,’ this is you doing something personally for somebody else because you feel called in your heart and soul to say, “Joe you did a great job today. I saw how you handled that patient and a difficult family, and that’s changed the way I’m going to communicate with families from now on.” There’s things that you witness in others that you want to emulate, let them know, “Wow that was really powerful the way you described this process to the patient, or to the medical student. That changed to way I looked at this disease.”

So I have a question for you all to contemplate. What, specifically, can you do to create a culture of collaboration in your medical institution? Just take a minute, maybe something I’ve said sparked an idea. I’m just going to let you all sit with this for a moment.

And if you’d like to please type this in your type pad and submit this, we could maybe share some of them at this point, because I know you all have really great ideas. I mean that’s the beauty in talking about this, and telling the truth, is that we have the intellect and the resourcefulness just in this room to change surgical training culture. Which then can be modeled by other residencies, family medicine.

Question: Dr. Wible there is a request to give an example.

Pamela Wible, MD: An example? Yes, I am going to give many examples in here. One example that I’m going to focus on at the end is just as simple as it sounds, giving thank you notes to people. Physicians really like to read, you might have noticed, and if you give somebody some appreciation verbally I mean that’s great, don’t hold back. However, we’ve got almost an emotional moat around us because of this culture of distrust, it’s hard. I don’t know if you’ve ever felt this way when somebody says something loving to you, it’s hard to really let it in? Especially if you’re busy and you’re going on to the next case, if somebody compliments you it’s like you don’t pause enough to take it in and get a little tear in your eye. You don’t pause, so actually writing it down and telling somebody, in verbal and written form, allows that person to read and re-read that over and over again. Because doctors tend to save their thank you notes, so that would create a feeling of, “Wow, I’m appreciated.” A lot of physicians don’t feel appreciated by each other, by patients, by administration.

Anything else that anyone would like to share? I’m going to go into that in more detail later.

So when you say, “listen to the residents more,” I have a great example of what you can do with residents that’s so much fun. In my introduction you heard that I did town hall meetings and I encouraged my community in Lane County, Oregon to design their ideal medical clinic, right? Because I learned how to technically be a physician and prescribe the right meds for strep throat, UTIs, and all that jazz; but nobody taught me how to actually run a clinic in a way that’s truly patient-centric. I believe in putting the end-user in charge. I believe medical students should design their ideal medical school. I believe residents should design their ideal residency, not wait for the ACGME to dictate all these things. Or at least collaborate so it’s not just a top-down mandate, “here’s how we’re going to train you.”

So one thing that I did just spontaneously when I was speaking to residents, I think it was a family medicine residency; is I just took some time, they passed out paper and pen and I said, “Hey, if you could be program director of your program, design your ideal residency. If you could be king for the day, or queen for the day.” They were nonstop writing all sorts of ideas that the program director was like, jaw to the floor, “I can’t believe you’re getting this level of engagement.” And then they started sharing, I think because I’m a neutral person that wasn’t evaluating them, right? They were willing to share with me, and somebody actually asked them their opinion. And the residency director was writing furiously all their ideas down, and these are things that they could implement that week. I mean it’s not a mystery. The problem is we haven’t asked the end-user to be engaged and mined them for the incredible resourcefulness and intellect that they have in designing, let’s just say, their ideal AO, their ideal surgical residency, their ideal clinic. These are intelligent people that should be treated like adults and not infants, and allowed to take a major role in creating what’s going to work for them.

So I’m going to talk a bit about physician mental health wounds which are generally, from that Afghanistan example, caused by competition.

Collaboration, when we truly collaborate beyond lip-service, there is a feeling of unification and like that we’re a family, and we’re all in this together. When we’re in competition, that creates isolation and people don’t feel safe to share anything. They don’t feel safe to share a failure that they had with a patient, or even admit that something got screwed up. They don’t feel safe to share their emotions with one another.

This is another quote from the book:

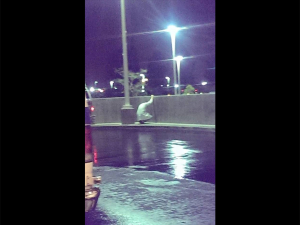

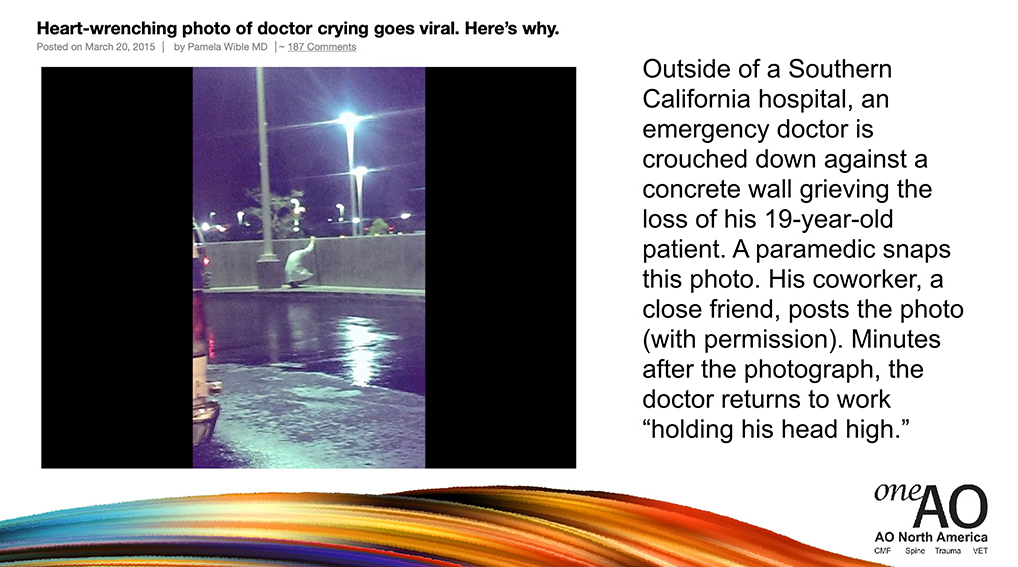

That is a key line there. People are experiencing things that they’re actively hiding from one another. And I want to show you a picture of what emotional isolation looks like.

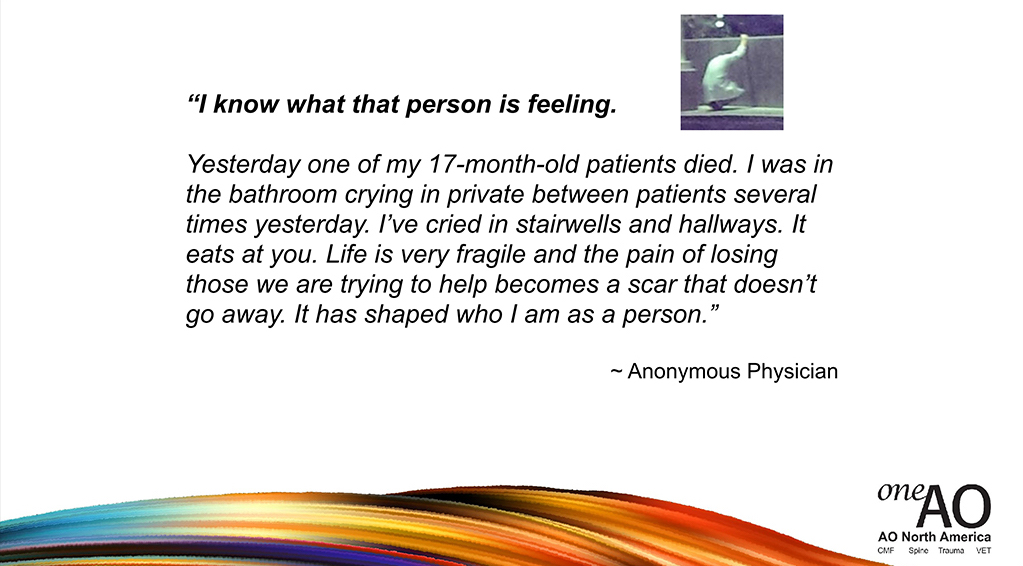

This is an actual photo of an emergency physician outside of a Southern California hospital, who just lost a nineteen-year-old patient. This paramedic snapped a photo, with permission they posted this online. This thing was going viral, it’s 2015. He’s crouching down, he’s against a cement wall and crying, by himself outside of a parking lot, and then having to go back in and see the next patient. The part that most people fail to realize is this man now has to compose himself, walk into another person’s room and introduce himself with a smile and handshakes. Not much time to debrief, there.

So I’m going to leave this picture up for a minute and give you the opportunity to see what comes up for you as you’re staring at this picture. Just jot down, maybe you’ve felt this way. Maybe you’ve cried secretly in the bathroom, or a stairwell. This is a real scene that plays out every day, most human beings that witness something traumatic. And if you’d like to type anything in your keypad about a feeling, or a thought that you have as you’re looking at this picture, we can hear, anonymously, anything that wells up in you. If there’s anything that’s coming in?

So these are some quotes, when this was going viral online, I believe this is from Reddit:

If you can relate to that, and you want to share anything about that, anonymously. So people who have experienced this, it’s sort of a form of almost carrying the PTSD back to the flashback-side earlier on. They can’t stop seeing the face of the mother. You’re viscerally experienced this like the blood, the last breath, the calling off the code. Even if you don’t want to intellectually sort of remember it, it’s in your body. The scream of the parent. These don’t go away.

And so what I’m suggesting is that we heal. You can’t sort of just meditate your way out of it, or have a green drink or something. These are well-intended, wellness maneuvers that I think some organizations are trying to create a nice environment for us; but what I would suggest we do is actually heal, triage, get to the root issue. Which is that, quite honestly, we’ve experienced vicarious trauma.

So there’s a sentence I really like called, “Hurt people, hurt people.” Now this isn’t because we’re mean. Some people say, “Oh, surgeons are mean, and men are aloof.” These are people who are hurt, and professional distance and everything else. You start to inadvertently wound other people if you’re wounded. I mean that’s just kind of what human beings do. You get stuck in a cycle, like that, and so I would encourage us to handle… we’re going to kind of have some really simple things that we can do, today, to really deal with this.

Another quote:

Can anyone relate to this quote? I mean just, I don’t know, raise your hand if you feel like you can relate to this. Feel free to send anything through your type pad that you’d like to share, about these quotes. I promise I’m not going to leave you in a state of misery, this is going to be very uplifting at the end. This is part of healing. This is kind of like doing an emotional I&D. You know what I mean? Get out, get the pus out. Anything you want to share?

So vicarious trauma you receive this when you hear patients’ stories of trauma. You are traumatized, even if you don’t think you are, you are. Witnessing patients suffering and dying, that’s traumatic. Most people wouldn’t even want to read a book about what you see and do every day, it’s too traumatizing. Experiencing medical errors even if they’re not your fault, someone else’s fault, people replay these scenes, “If I would’ve done it this way, if I would’ve taken this approach, if I would’ve started this procedure earlier.” Exposure to traumatized colleagues. If you think about we’re all suffering from vicarious trauma, we’re all going work today in the same medical institution; we’re all trying our best but we’re all suffering, silently, together, packed in close in these buildings, with people that are in charge that are not doctors, unfortunately, and they don’t understand what we’re going through and we don’t even reveal it to each other, so it’s just kind of a mess that way.

So to create a culture of wellness, culture actually determines our trauma-response. We tend to respond… medicine is an apprenticeship-profession, so we see how other people are responding to trauma and then we do the same thing. So if they just shut down emotionally and go to the next patient, then we just shut down emotionally and go to the next patient. If nobody’s talking about, then we’re not going to talk. No one wants to be the first one to talk about it.

So these are some things that we can do that are very easy. We could have a recovery room for doctors and hospital staff. There’s probably a broom closet in every hospital that’s not being utilized. Turn that into a recovery…patients have a recovery room, what about a recovery room for doctors? You know how many chaplains have called me over the years saying, “I want us to help doctors who are suicidal, what can I do?” Well, the doctor calls you to help with the family that lost the infant, but maybe after you have a conversation with them you can have a confidential conversation with the doctor that just saw the infant die and had to tell the family. So it’s like we already have staff in the hospital that are willing to listen to us with empathy and love, they’re called chaplains; and why don’t we create a scenario where we’re willing to receive help from chaplains without being punished, without it going on electronic medical record, going to a psychiatrist and all this stuff, right? That’s one thing that we can easily do.

Peer-to-peer support, which is sort of what I’m suggesting we do for the rest of this conference. If anything that I say up here resonates with you, you might have a conversation with somebody about something that you’re feeling as a result of this talk. Balint groups a really interesting way to do it, where you discuss a patient case related to your own emotions around it. You can look it up, it’s a structured form of sort of almost group therapy for surgeons, without calling it group therapy.

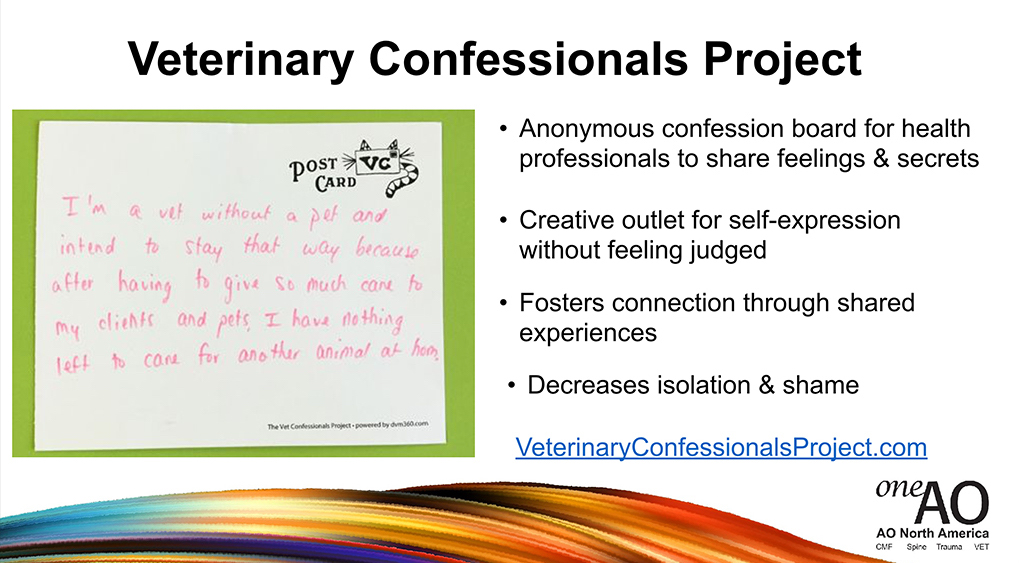

The Vet Confessional Project, I’m going to share a little bit about that, which is really cool. Has anyone heard about the Vet Confessional Project? So awesome, very easy. My solutions, by the way, are no-cost solutions. They don’t cost anything and they can be done right away. Confidential medical mental healthcare, I think, is essential for physicians. And trauma-informed care.

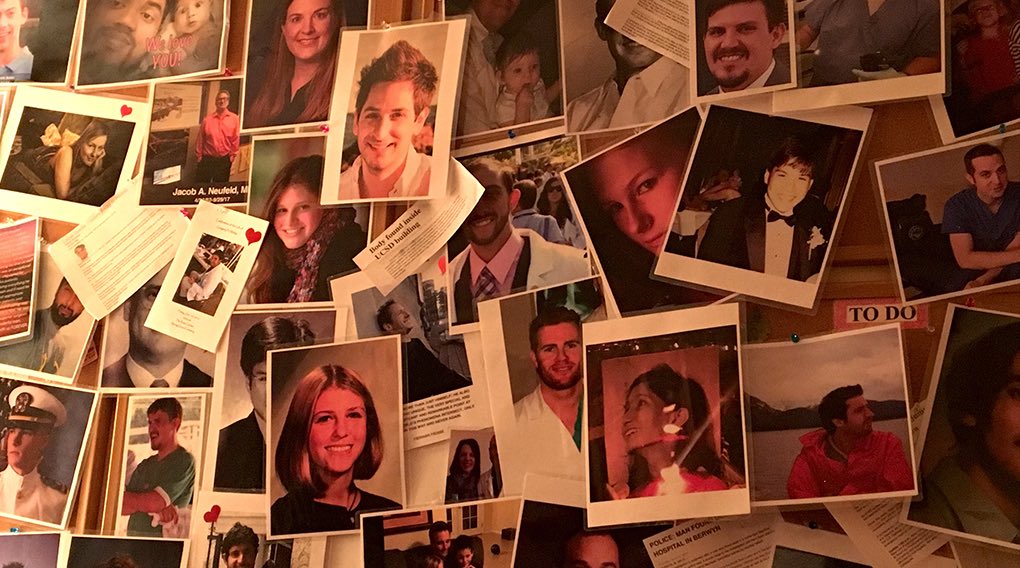

So, I want you to look at a picture here, this is actually a wall in my home business office. These are some of the 1363 doctor suicides that I’ve investigated. I’ve been on the phone with their families and listened to the mom crying on the phone that lost her only child in medical school. As you’re looking at this photo which is painful to look at the faces of beautiful doctors that didn’t get to fulfill their career aspirations. Some didn’t even make it out of medical school or residency.

I want us to take a moment to honor a man that you lost as an orthopedic surgeon, recently, on September 17th last year. You lost Thomas Fishler, does anyone know Tom Fishler? Okay. So he died, actually this is so strange, the 17th of September is National Physician Suicide Awareness Day. That’s when he died, and so to remember him and take a moment. If there’s anyone else that you’ve lost that you’d like to remember at this time, just honor. These are valuable people, who’ve contributed so much, and they deserve to be celebrated for their contributions.

Another gentleman I want to bring up is Steven Ortiz. Does anyone know who Steven Ortiz is, a spine surgeon? Three years ago today he decided to die by suicide. In the late hours of three years ago this evening, he checked on his patients in the hospital in Florida, and then went out to the parking lot and shot himself in the heart around 2:00 in the morning. Another wonderful orthopedic surgeon.

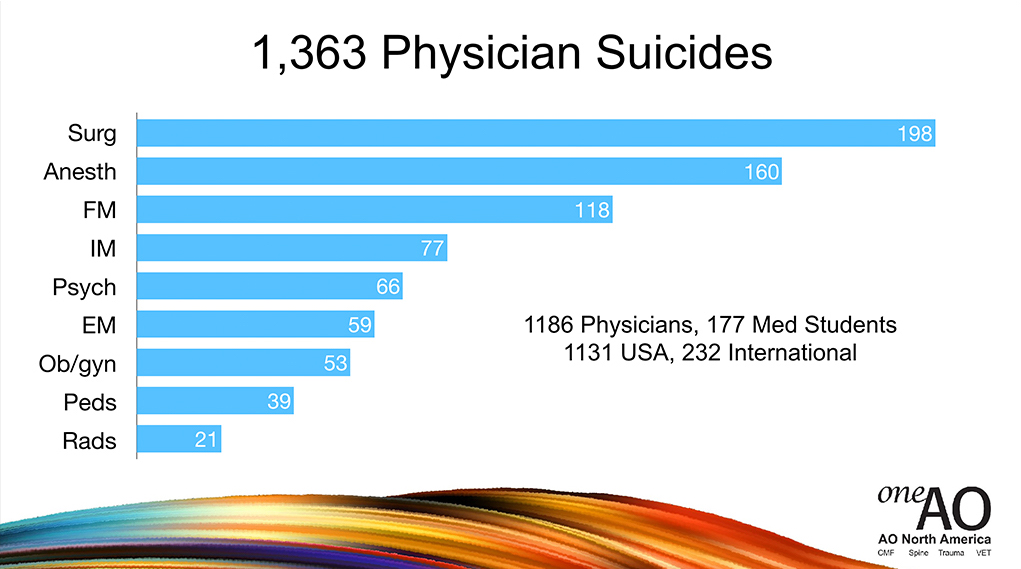

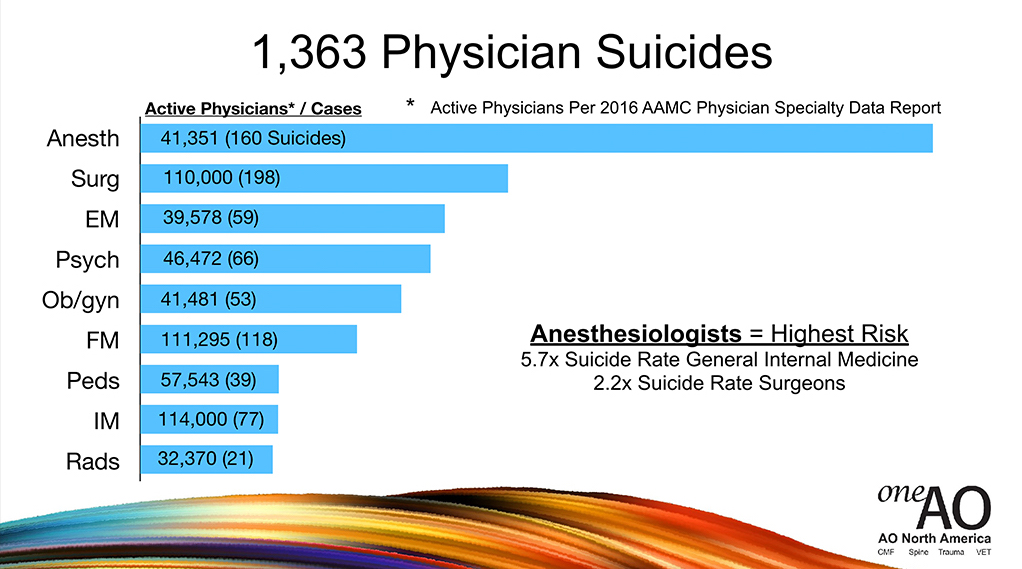

This is a graph of the number of cases, by specialty, that have come to me, just organically because I have a suicide helpline and people just submit, organically, names to me over the last seven and a half years. You can see that surgeons are in the lead with just raw numbers, and then anesthesiologists. But what’s more important is the next slide, which is if you do a calculation based on numbers of active physicians per specialty you can start to see that anesthesiologists are far in the lead, and surgeons are number two.

Anesthesiologists are dying 5.7 times the suicide rate of general internal medicine, 2.2 times the suicide rate of surgeons, I mean none of this is not anything to sneeze at. This is serious stuff. We’re going to talk about how to stop this from happening again.

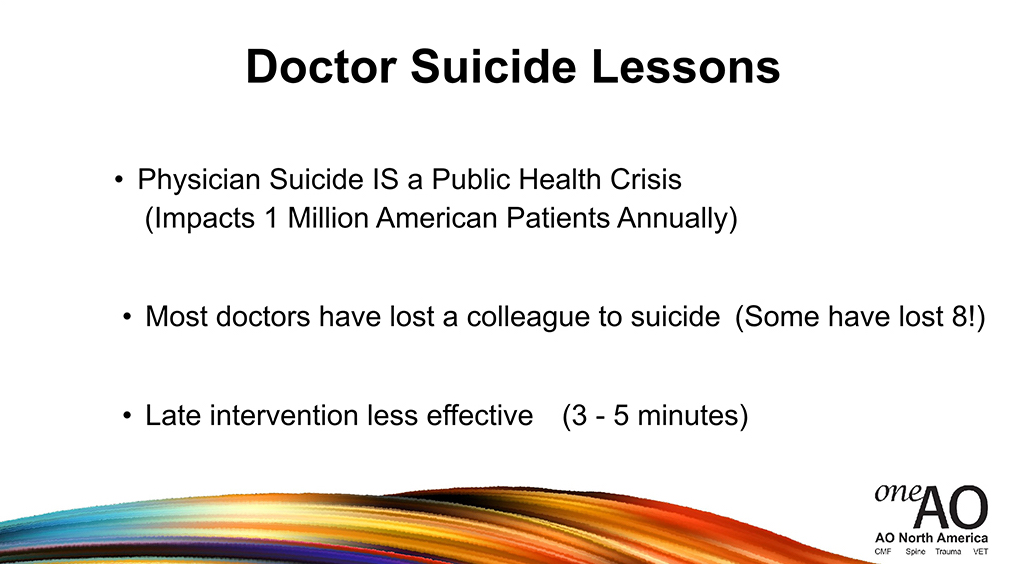

Here are some lessons I’ve learned. Physician suicide is actually a public health crisis. More than 1 million Americans lose their physicians every year to suicide, and I feel like it should be handled as if it’s a crisis. Most doctors have lost a colleague to suicide. Some have written me and told me they’ve lost eight colleagues to suicide. Late-intervention is less effective. I interviewed several male physicians who survived suicide, and they say between the time when they decided they were going to die by suicide and actually grabbed the gun or took the knife or the pills or whatever, 3-5 minutes. So see if we wait until very late, the heroic moves you’d have to make to save somebody in the last 3-5 minutes would have to be extreme. So I’m suggesting that we get ahead of this.

Just so you know, you might have noticed with the names that have come up to you, Steve Ortiz checking in on his patient just before he died, nobody saw it coming. These people have a great work ethic until their last breath, which is why we don’t know and we’re shocked when it happens. We die to end our pain, not because we want to die, but we don’t see any other way out. Anesthesiologists and veterinarians are likely the top two groups, and surgeons are number two.

So to create a culture of wellness, specifically for the people that AO serve, I want you to know it seems as if, from an outsider family doc’s perspective, the greatest trauma-exposure likely happens in your specialty. You, I believe, are the most overworked and sleep-deprived. Maybe OBGYN, too. Easiest access to painless, lethal means. So I think this scenario puts you at highest risk.

So we’re going to do a little institutional triage here, because before we can create a culture of wellness we need to diagnose what is most unwell, and treat it first. This is another book that I recently wrote, because I analyzed these 1363 cases. As a scientist you’re looking for patterns, so I saw some patterns of things that people would repeat over and over again, throwing them into this desperate realm.

I did a root-cause-analysis and I identified 41 different human rights violations in medicine that lead physicians to suicidality. Because to keep somebody up 72 hours or whatever, 36 hours, not letting them sleep; that’s like a torture technique that’s used in war. Bullying, sexism, harassment. The fact that we can’t get mental healthcare without feeling like our confidentiality is going to be breached, we’re going to lose our license. Corruption, that’s actually what killed Steven Ortiz, is corruption. He was working for a hospital system that actually incentivized him not to give surgical care to patients, and before that he had another job that incentivized him to over-deliver surgical care to patients. And so the conundrum of being in corrupt hospital systems tears at your heart to the point where you go out and shoot yourself in the heart in the hospital parking lot. Discrimination, exploitation, retaliation.

Okay so we’re going to now switch to the optimistic part of the talk. I just wanted you to see that it’s really important to recognize the depth of our suffering and not just say, “Let’s all meditate.” Right? We have suffering.

Comments: At the end two interesting comments and a question that I wanted to share. Someone said, “I remind myself, if I influence one patient positively each day, then it is life well-lived. Shit happens, but you’ve got to go on.” And another interesting comment, “We’re actors, overwhelmed with the act. We have to remember, this is just an act.”

Question: “Are you aware of studies that compare doctor suicides globally?”

Pamela Wible MD: Globally? Yeah, I don’t know globally. I can just look at the cases that come in India, it’s very high. I couldn’t say, some of this is just very well-hidden. We’re still calling some suicides accidental overdoses; which is an interesting thing to say that a physician can do because we certainly know the power of what we’re taking, we’re not a toddler playing with pink pills on the bathroom floor. So I think a lot of times, and of course the person filling out the death certificate might be your friend in a small town, and what are they going to maybe say it’s an accident so your spouse can get the life insurance payout? There’s a lot of things, culturally, going on here that cover this whole thing up, so we don’t really have accurate data. And certainly globally, I mean I’ve had people write me from Nigeria saying, “No suicides ever happen in Nigeria.” There’s a cultural feeling like “This doesn’t happen in our country, it’s just in the US.” Again, we’re shielded in secrets, secrecy.

But there are simple actions we can take today, and I want to say what the actions are not. Now these are well-meaning things that people have done, but these are not the solution to what’s going to help us create a culture of wellness. This is an actual thing that they did in the military, where they had them color in adult coloring books. They had to sign up, these are doctors who have patients waiting, you can see screaming in the background there, but they thought it would be good to have a mandatory wellness day. Everyone got to pick their adult coloring book and coloring rainbows and stuff, but that’s actually not a targeted treatment for what ails us. And by the way neither is burnout, which I cannot stand that word. Or moral injury, I don’t like that word, either, because this is not a definitive diagnosis.

Moral injury, probably who’s heard of moral injury? Moral injury, I mean it’s circulating around. That’s like if I called you from the emergency room and said, “Hey, I got a leg injury in here,” and you said, “Well what’s going on?” and I said, “I don’t know, leg injury.” Is that going to be enough information for you to start making a decision? That could be anything from a sprained ankle to a displaced femur, what is that? I don’t know. Moral injury, so nebulous it means nothing. I mean there’s no treatment plan attached to it. I’m talking about taking action today with a definitive diagnosis and a treatment plan. Let’s not stay in nebulous territory and denial about the extent of the problem/ Even if it is sometimes too hard to talk about. Staying in denial about a fractured femur doesn’t allow you to move forward with the treatment.

Also, I went to an AMSA convention where they recommended to survive residency you just have to take up swing dancing. There was a whole lecture on swing dancing. I think if we had free time, we’d probably naturally go out dancing. You know what I mean? But this is not going to help the situation we’re in.

Keeping a gratitude journal. Boy that sounds like fun, but how’s that going to help with vicarious trauma and the pain if you just lost an infant? You know what I mean?

Meditation and yoga, all right. I’m just saying these are well-meaning, but not targeted treatments. Let’s use a targeted treatment. Like sleep deprivation, what’s the treatment? A pillow. Hypoglycemia up for 36 hours? Food, dinner. There’s actual treatments, okay? A psychiatrist at a conference that her solution for burnout was to start running marathons, and she was telling everyone, teaching the doctors how to set goals. It’s like, wait a minute, we already know how to set goals, we made it through med school. Doing more activities that are not emotionally healing the real wound isn’t necessarily going to help, either is a whole bunch of wellness lectures.

So what I’m talking about that we can do that’s targeted treatment, to create a culture of wellness is I’m going to talk about two things on this slide, which I’ve previously presented. One is the Vet Confessional, which I think is awesome, and how to actually have confidential medical mental healthcare.

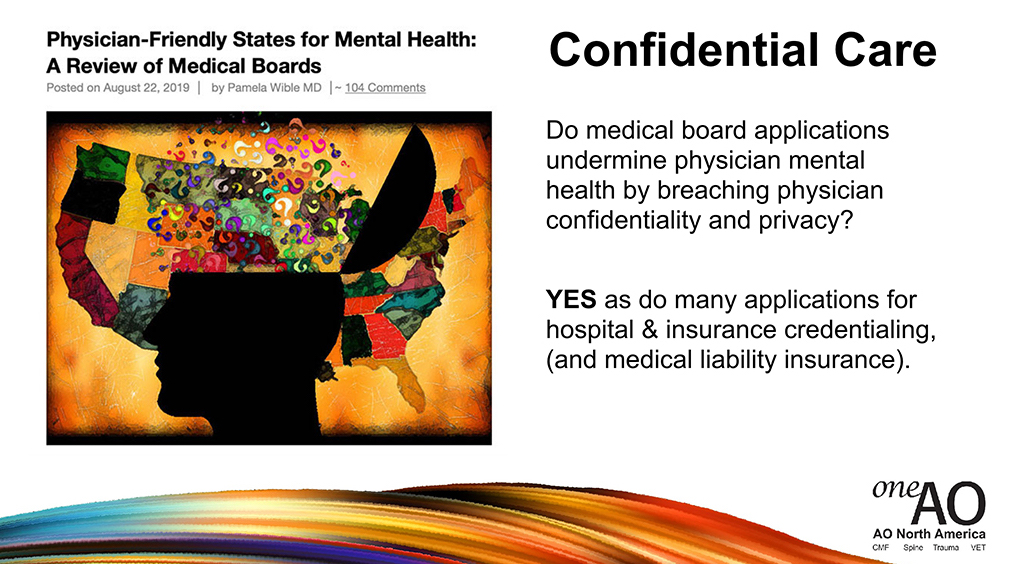

So I did a study this summer with an intern, oh my gosh it took us three or four months. We went through every state’s medical licensing application, the initial licensing application, and we pulled out all the non-ADA discriminatory questions on mental health. Because physicians, they’re not going to go seek help if they feel like… if Tom Fishler feels like, by going to a psychiatrist or talking to a psychologist that’s going to go on his record, and he might lose his medical license, very unlikely that he’s going to do that.

So we have to have confidentiality when we share our pain, and right now medical boards are breaching our confidentiality, which is illegal under the Americans with Disabilities Act. I mean, yes, they need to find out if you’re currently competent to practice medicine, but it’s none of their business if you have remote postpartum depression or were going to marriage therapy, that shouldn’t be discoverable by the board. Applications for medical liability insurance, insurance credentialing, hospital privilege applications, medical boards. They’re often asking, “Have you ever had depression? Have you ever? Have you ever?” It’s none of their business. What you need to know is, are you capable of practicing medicine now? Are you competent now? Right?

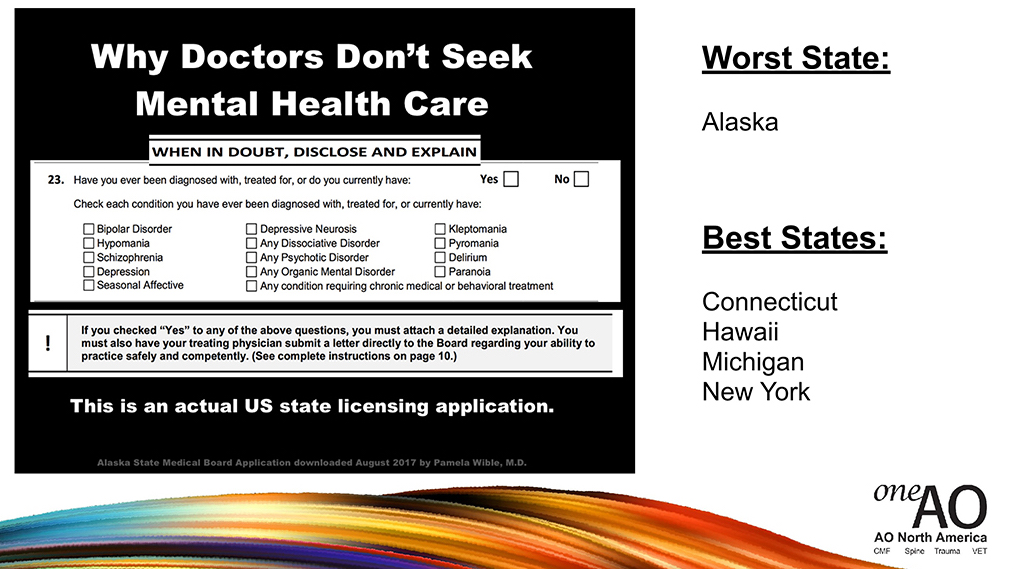

This is an actual application from Alaska that’s still being used, in which Alaska, this was the worst state, asks 25 yes-or-no mental health questions. Does that seem extreme to anyone? I don’t know does that seem extreme, right? Now the best states, Connecticut, Hawaii, Michigan, and New York ask no mental health questions. So there’s precedent for doing this differently.

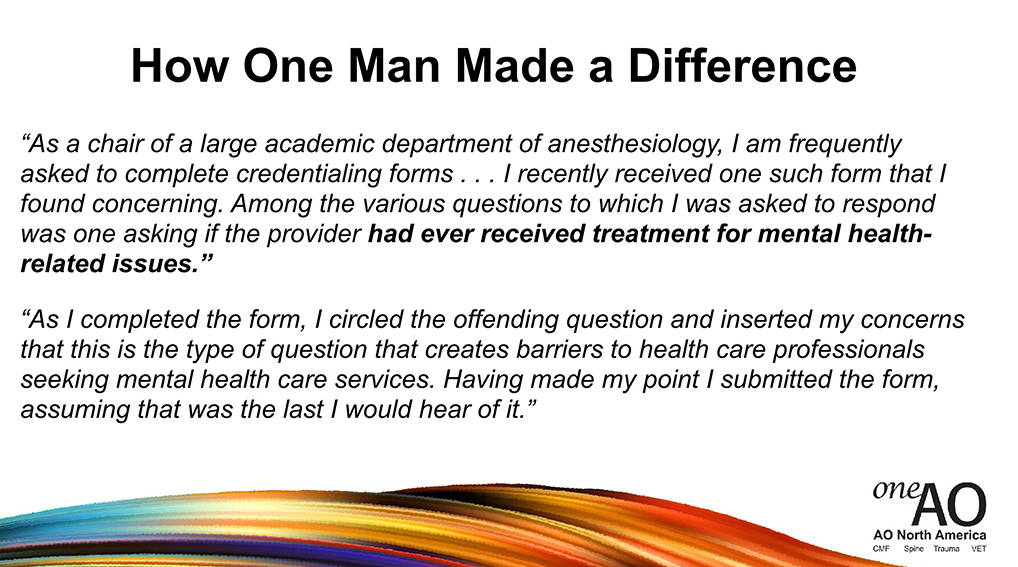

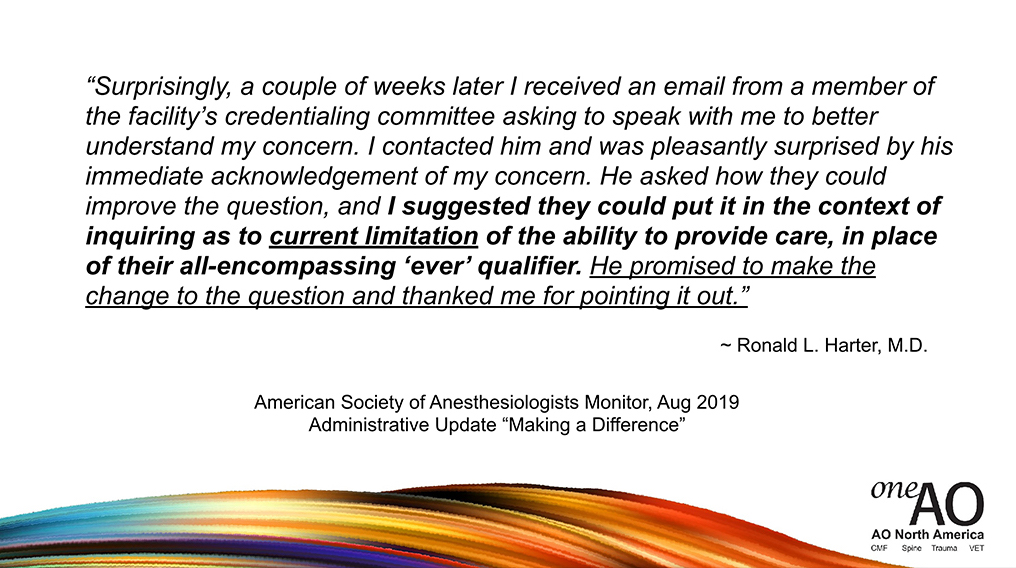

And I want to share how one man made a huge difference. This was an anesthesiologist who essentially, to cut to the chase, basically was asked for a peer reference on another anesthesiologist, okay? He saw there was a “Have you ever had” question on there, he circled it and said, “This is creating stigma. I would request that you change the way you’re asking these.” This came from a hospital credentialing committee, right? He said that, “This is not a question that’s helpful,” right? Now the hospital credentialing committee, the doctor in charge there actually wrote back to him and removed the question. People sometimes don’t realize these questions, which we can just remove from our applications in our departments, in our hospitals; will make people feel safer to get the care they need.

So my question to you is: What action can you take or have you ever taken to protect physicians from being asked to disclose their confidential mental health treatment?

Some of you are in charge, some of you are on credentialing committees, I know. Some of you accept residents into your programs. Are you asking mental health questions that are against the Americans with Disabilities Act? Should be kind of a never event. There’s no reason for us to go into this territory.

Question: ”Is access to medication and addiction a factor?”

Pamela Wible, MD: Yes, because substance abuse…basically that’s a late-stage maladaptive response where you are coping by drinking alcohol at home. Or sometimes driving, there’s doctors that drive 200 miles out of town to use a fake name and cash to get mental healthcare, because they don’t want to go sit at a psychiatrist’s office, psychologist’s office in their small town in Tulsa, Oklahoma or wherever they are and they drive out of town. I mean, that’s like sneaking around to try to get screening colonoscopies. You know what I mean? It’s putting us in a terrible situation. Yes, it is a huge factor and the PHPs, which I could go into there’s a lot to say on this. By the way, I’ll be here the whole day if anyone needs to have a private conversation with me, I’m going to be accessible and obviously I have a passion for this topic.

Question: How does compassion fatigue play into the cost of suicide?

Pamela Wible, MD: So compassion, you’re spent. With compassion fatigue you have no emotional strength left. In fact, I interviewed a series of family docs and asked them “At what point in the day, after how many patients do you sort of stop caring?” Usually we have 28 patients a day or so we see in family medicine. They say “at about 10 I just stop listening. I can’t hear anymore tragedies.” So the last two-thirds of the patients you see per day are sort of getting only a portion of your attention span. So yes, compassion fatigue plays out daily and it plays out over your lifetime. And then honestly, you go home and you certainly don’t want to hear your child complain or your spouse, and you’re like, “Get me some alcohol. Let me get stoned.” You’re just thinking, “What can I do?”

Question: Is suicide more a problem in affluent culture?

Pamela Wible, MD: Is suicide more a problem in affluent? I mean, suicide in general among physicians? I think there are children that get pushed into medicine and it’s not their right profession, in Asian culture, by the way, and some Jewish families. “Be a doctor” sort of a thing. Those are affluent and non-affluent families. There’s actually sort of something that comes up to me is when, there’s been physicians that have died by suicide and I look in their family and every single other person in their family is a physician. So what goes through my mind is, “Do you pressure your kids to go into medicine?” Do we all need to be in matching professionals, like matching circumcisions. ”Did you pressure them to look just like you and be in the same profession?” You know what I mean? Let people choose their own profession.

Comment: ”Largely that’s unmentioned the impact of institutional productivity expectations, cornering physicians into circumstances.”

Pamela Wible, MD: Right, so I think we’re moving at speeds, because of the EMR, that are not human speeds. We’re moving at a high pace that we can’t sort of, our technology has outpaced our spiritual and emotional ability to keep up, and even our physical ability to keep up. But I want to share an inspiring answer, here.

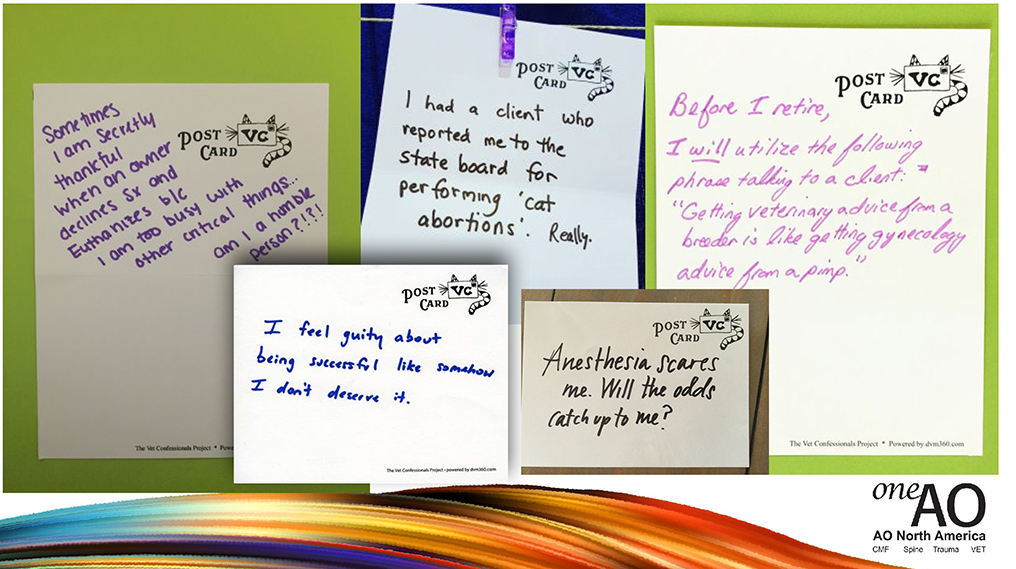

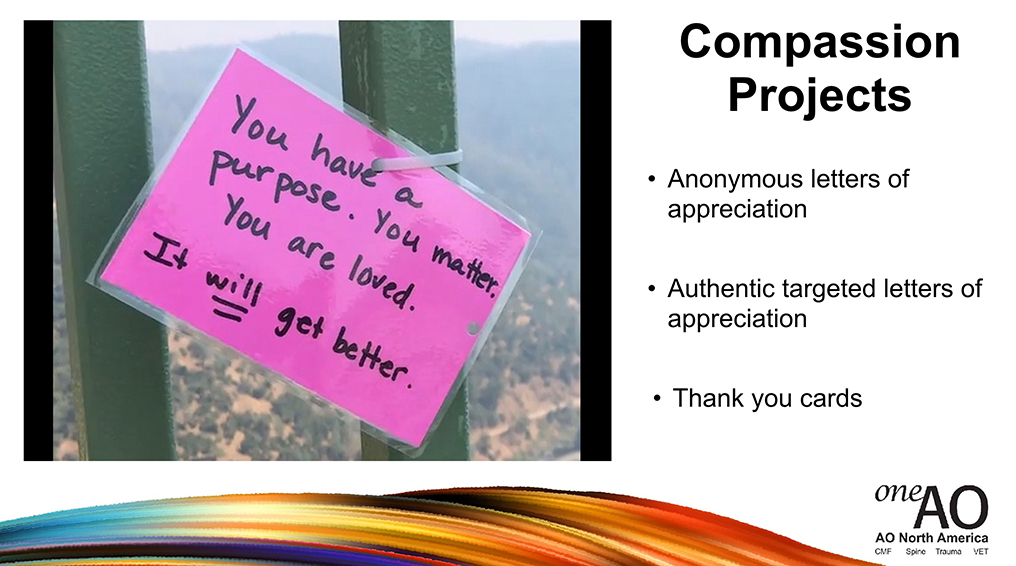

This is called the Veterinary Confessionals Project, which they actually do at veterinary conferences and there’s an online forum where this is happening, where veterinarians can submit their confessions, kind of like going to a Catholic confessional thing, right? So, “I’m a vet without a pet and intend to stay that way because” probably compassion fatigue, right? “Having to give so much care to my clients and pets I have nothing left to care for another pet at home.” Some of you probably feel that way with your home life, nothing left to give. These are anonymous confession boards for health professionals to share feelings and secrets, it’s a creative outlet for self-expression without feeling judged because it’s anonymous, and it fosters connection through shared experiences. This is actually targeted, people are feeling pain and they have an anonymous outlet.

If anyone has a secret they’d like to confess, send it through your type pad. We’ll read it and we’re not going to know who sent it. It decreases isolation and shame. There’s an actual website you can go to if you’re interested in this. It’s free, like it would be just hanging up cards outside of a conference, having a little wall with post-it notes. I’m going to read a few more.

You might have feelings like this, I’m going to take a moment here for you to send anything that you’d like to confess through your type pad. This way, please, and see if you’re willing to share. I would encourage you to write some things down for yourself, get it off your chest. Because carrying around “I feel guilty about being successful” or “When will anesthesia catch…” these are fears that you carry around every day like in a backpack and you’re just walking around the rest of your life with these things on your back, and it’s just good to get it out somehow. Even anonymously.

Question: ”How do you identify doctors at risk now?”

Pamela Wible, MD: That’s the problem because of our “stay happy and smile, wear your white coat,” we have to put on a game face every day, it’s very hard. I would say anyone who’s expressing any sort of struggle, you could probably increase that 10 times. I think all of us have probably thought at some point had some sort of passive suicidal thoughts creep in. “Is this really worth it? Did I make the right decision? Am I in the right career? Maybe it would be easier to drive off road into a tree.”Like, “I wish I could trade places with my patient in hospice and get some rest.”

Read: Why happy doctors die by suicide (top 10 article of 2018 on Medscape)

So until we start revealing our secrets, randomly and honestly, on a confession board or on our diaries, or start talking to each other as peers, I think it’s hard to make any progress. I would treat every doctor like they’re a potential suicide case and be like, “Joe it’s great to see you, how are you doing? I haven’t seen you in a while let’s go to dinner, let’s talk.” Just interact with each other as if there’s a possibility that this could be your last conversation, I know that’s kind of a doomsday thing, but I mean if we can get connected at the heart and soul I think it will really, really help people feel safe and willing to share.

And the way to do this is, because you know guys aren’t going to hug each other and start crying? Like women, by the way, we have a lesser suicide rate I think because when we’re feeling so upset we start crying and call our girlfriends up and we get it off our chests. I don’t think that’s how men respond, they have a gun and they just go out back and they shoot themselves. You know what I mean? THat’s what I notice. Men it’s the testosterone, the impulsivity and the fact that they have access to lethal means and they’ve just had it because their wife asked for a divorce, or something happens. You know we’re very compartmentalized it only takes one little thing to push them over the edge.

So I’m just suggesting that for men, what you might want to do is go fishing, go to a hike in the woods, and you be the first person to share some sort of secret. Like, “Hey, I’ve never shared this with anyone, but I feel safe. I’d like to share that, hey, I lost a patient five years ago, it still eats at me.” If you go first, then probably the other guy will be, “That happened to me, too, in residency and I still see the face of the other.” I think you just have to start walking that path and sharing it relieves people.

One thing I want to say that I think is so very inspiring, is that people will write me these long emails about their tragedies and at the end they’ll say, “I don’t know if you’re ever going to read this, but I feel so much better that I wrote this to you and got this off my chest. Don’t worry about calling me back, I just feel such a relief that I wrote this down.”

So my question to you: What do you think about starting a confessional project at your medical institution? Does that inspire anyone? It’s very easy. Something you can think about doing.

But the last thing I want to mention before I close is the value of appreciation. So, I touched on this earlier, expressing appreciation to physicians through personal action. Basically what I’m talking about it is just, pretty much like I said, take a physician out to dinner or lunch. Give a gift to a physician who’s inspired you, a thank you card. Offer to take call for a physician. These are very simple things you can do. But, the simplest thing I want to end with is just thank you notes. The value of telling somebody, “Hey, Mike. I saw what you did and that really touched me.” Even a text or a simple thank you card. And I want you to know that a thank you card, by the way, has actually prevented physician suicides, okay? “Having practiced medicine 45 years I was always lifted up when patients thanked me.” The number of people who’ve actually written me to tell me that a thank you card prevented their suicide, is really quite a lot.

This is a project that a teenager did on a bridge that she was about to jump from, and she decided not to and she left little love notes on the bridge.

People, who also thought of jumping from the bridge, found the notes then found her and thanked her because that note saved them and prevented them from stepping off the bridge. This is as short as a thank you note needs to be, “It looks like you had a hard day, Jim. It’ll get better. I’m here for you.” Something very simple can change somebody’s entire life. I mean it seems unlikely but it’s really, really important. You have no idea how much a kind word can prevent a suicide.

You don’t have to even use love words or pink cards, you can just use blue for boys. ”I saw what you did, Jim, and you’re a great guy.” Whatever makes this palatable for you, but I’m encouraging you to do this because:

But to close, my final slide, this is an actual text that prevented an ENT doctor’s suicide. This is from another ENT doctor or resident:

You don’t even have to pick out a Hallmark card. This one text actually saved an ENT doctor’s life and I just want to sort of close there, I probably went over, but if you have any thoughts about any of this and how simple this really is. I mean the one thing I’m going to leave you with, if you could just get in the habit of texting appreciation to one another? You will create a culture of wellness that will have ripple effects to no end. Simple, you don’t have to wait for a committee meeting.

Comment: “I personally thank, by name, every person in my op room before I leave at the end of a case.”

Pamela Wible, MD: Any other thoughts about the simplicity of some of this? I mean really the revolution that we need, culturally, is from the inside-out and the bottom-up. Which is why when a top-down mandate to do adult coloring books doesn’t really work, you know what I mean? The systems are just made up of people, as each one of us change our behavior with one another, the entire system changes. And it’s very beautiful and can happen quickly. I would encourage each one of you for the rest of this conference to maybe share some authentic feeling with another person here, and have a depth of conversation that’s different than just comparing surgical techniques. Consider going into an emotional realm with each other for the next few days, just with one person. See how it feels, check in with someone. Tell somebody you appreciate them. Maybe send a text back to some of the doctors stuck in the tornadoes, and let them know how much you appreciate them even though they couldn’t make it or support residents back home with some appreciation. That’s my parting request, the culture change starts in your heart and soul.